Residual sugar seems like an obvious concept. Residual sugar. Sweet stuff, left over. In wine. But like many concepts in the wine world, it’s not that simple.

Yeast eat sugar to make alcohol. This much we all know. So why would the yeast stop before all the sugar is gone? It’s a good question, and it’s one that’s not always easy to answer. But one (or more) of the following is often the matter:

Yeast eat sugar to make alcohol. This much we all know. So why would the yeast stop before all the sugar is gone? It’s a good question, and it’s one that’s not always easy to answer. But one (or more) of the following is often the matter:

[box]

- Too much sugar – and too much alcohol resulting from too much sugar. It’s kind of gross to think of it this way, but yeast will die from wallowing in their own excrement, since ethanol is a waste product of yeast metabolism. Like people, different yeast strains have different alcohol tolerances, but most cop out around 14-18% alcohol by volume (ABV).

- Fortification – fortification is both a way to make and a way to deal with accidentally sweet wine. If you want to stop yeast from finishing off the sugar remaining in a wine mid-ferment, adding a bunch of ethanol (enough to bring the batch up to at least 18% ABV) is the easiest way to do the trick. Fortification is also an efficient way to keep an accidentally sweet wine from spoiling. With all of that sugar sitting around sweet wine is an easy target for spoilage microorganisms, but there are very few yeast or bacteria that can grow in 18% alcohol. This is how port and other sweet fortified wines are made.

- Malnutrition – Probably the most common reason why yeast lose their mojo. Yeast need more than just sugar to survive, and if they run out of something else first—nitrogen and cell wall components are the most common limiting factors—they won’t finish the fermentation.

- Something killed them – if a winemaker wants to create a sweet wine without fortifying it, he or she can filter the wine to remove the yeast and then optionally add preservatives to ensure that a few cells don’t multiply and restart the fermentation or contaminate the batch. In addition to sulfur dioxide, potassium sorbate or potassium benzoate is often added to keep yeasts and fungal spoilers at bay.

(There are a slew of other causes of “stuck fermentations”—fermentations that stop before all of the sugar is gone when the wine isn’t intended to be sweet—but that topic is too big to tackle here.)[/box]

The most obvious reason to deliberately leave much residual sugar in a wine is to make a sweet wine, but there are other good reasons for leaving a little sugar in a wine that isn’t perceptibly “sweet.” A recent study in the Journal of Food Science showed that tannins precipitated less salivary protein in the presence of some fructose than in its absence. In other words, there is a scientific explanation for why red wine seems less astringent when it’s just a bit sweet. I’m waiting for someone to do the study showing that some residual sugar mitigates the “foxiness” of native and hybrid grapes and to help explain why so many wines made with these grapes have evolved to be significantly sweet. Or maybe people who enjoy hybrid wines also enjoy sweeter wines. I don’t know, but I think that it would be interesting to find out.

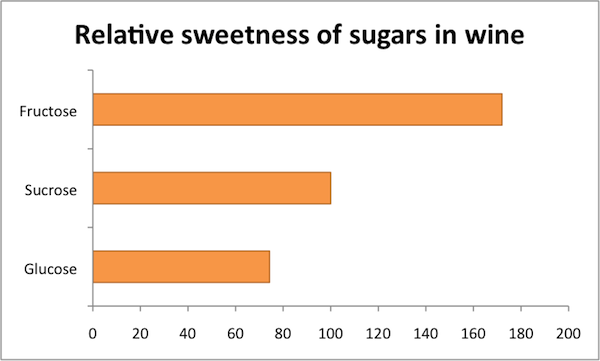

Now, the real fun comes in when we consider that all sugar isn’t created equal. Sugar comes in many flavors, though they are all more or less sweet. The “more or less” part is important, as some forms of sugar taste far sweeter than others. The vast majority of sugar in grapes is either glucose or fructose—both six-carbon sugars—plus minor amounts of disaccharides like sucrose and pentoses, which are five-carbon sugars. Grape juice starts off with about equal (molar) amounts of glucose and fructose but, since yeast reliably go after glucose first, residual sugar is heavy on the fructose. This is important because fructose is about twice as sweet as glucose and nearly twice as sweet as sucrose—ordinary table sugar—so the residual sugar in wine likely tastes sweeter than you’d expect based on your experiences with table sugar. Yeast won’t touch the pentoses at all, though these are pretty insignificant both because they aren’t very sweet and because there isn’t much of them.

Returning to our initial question—what the heck is residual sugar?—we’re now faced with the question of which types of sugar are counted in this residual amount. Is residual sugar all sugar—glucose, fructose, sucrose, pentoses …—or are we just talking about sugars that yeast can ferment? Naturally, it depends on how residual sugar is measured. The most common way to measure sugar in wine only measures reducing sugars like glucose and fructose, but not sucrose. In most cases that means that all of the sugar in the wine is being measured, but there’s one notable exception: chaptalization. When winemakers add sugar to must, they often add it in the form of sucrose—table sugar—because sucrose is cheap. If the yeast don’t digest all of that sucrose (after breaking it down to its component parts, glucose and fructose), the wine may contain more sugar than the standard measurement would suggest.

We don’t usually perceive sweetness in a wine until it has at least 0.2% (2 g/L) residual sugar, and many dry table wines contain less than that. It’s worth remembering, though, that all that tastes sweet isn’t sugar. We perceive sweetness based on the geometry of molecules that interact with taste receptors specialized to register sweetness. A molecule capable of forming several different bonds at precisely the right angles with the molecules of the taste receptor will activate the receptor and put in motion a pathway of neurons that collaboratively communicate, “this is sweet!” through your brainstem and your thalamus up to your cerebral cortex.

Both ethanol and glycerol taste sweet if you taste them by themselves, dissolved in water. Since there’s plenty of ethanol and a fair bit of glycerol in wine it would seem reasonable to think that these compounds contribute to wine’s sweetness, but some relatively recent research tells us that this isn’t the case—at least for Australian Riesling or red Bordeaux—and that ethanol and glycerol don’t make a difference how sweet a wine appears to be.

In fact, wine chemists are still actively discovering compounds that make wine taste sweet. Considering how simple sweetness seems to be, I think this is pretty incredible. Just last year a group of French researchers found that the reason why red wine seems sweeter after sitting on its lees (dead yeast cells) is because a peptide (think small piece of a protein) that yeast cells release as they break down tastes sweet. Improbable as that may seem, it isn’t that unlikely; aspartame, that love-it or hate-it artificial sweetener is, after all, also a peptide. Another group of researchers, also French, also last year, found a sweet-tasting compound derived from oak—quercotriterpenoside (whew!)—that might be responsible for the common but heretofore unsubstantiated belief that wine tastes sweeter after some time in oak. No one has established that either of these compounds makes a significant difference in how wine actually tastes in practical terms but, well, it’s a start.

Finally, I feel obliged to mention something that is virtually inescapable when talking about sugar these days: calories. Alcohol is usually a far more important determinant of the calories in wine than is sugar; not only is there more alcohol than sugar in most wines, but sugar rings in at four calories per gram while alcohol has seven. Because the only significant sources of calories in wine are sugar and alcohol (flavor molecules don’t amount to much), determining a rough calorie count for any given wine is really quite simple:

[box]

[/box]

Or if you’d rather skip the math you can use this handy calculator:[box]

Wine Calorie Calculator

A standard glass of wine is about 5 oz. A bottle is 750 mL.

RS is sometimes given in %. 1% is 10 g/L.

[/box]

Calculating the calories in a glass of wine is easy. The hard part is finding out how much residual sugar is in the wine you’re drinking. A very few info-happy wineries list residual sugar on their labels; more provide this information in technical notes available on their websites, so this is a good place to look if you’re interested. More often than not, however, the only way to obtain residual sugar information is by emailing someone to ask. Unless you’re a serious calorie-counter or have a specific health concern knowing residual sugar numbers is more a parlor game than anything else. Growing up, guessing a wine’s residual sugar was a competitive sport for my father and me (yes, we’re geeks.) But I think that it’s true for many of us that a big part of appreciating what fills our glass is knowing why it tastes the way it does. Sometimes that means knowing the story of the vineyard, the grape, the winemaker. Sometimes that means knowing the story surrounding how and why the molecules dancing in that glass dance the way they do. Residual sugar is an important part of that dance.

After all this talk of sugar, I’m ready to reach for a crisp glass of Chablis—or a gin and lime—to neutralize all that sweetness. Why does acid counter sweetness? Come back next month and we’ll talk.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/yoga-headshot-2010-thumb.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Erika Szymanski was blessed with parents who taught her that wine was part of a good meal, who believed that well-behaved children belonged in tasting rooms with their parents, and who had way too many books. Averting a mid-life crisis in advance, she recently returned to her native Pacific Northwest to study for a PhD in microbial enology at Washington State University. Her goal, apart from someday having goats, is melding a winery job to research on how to improve the success rate of spontaneous ferments. When tending her Brettanomyces leaves enough time, her blog Wine-o-scope keeps notes on why being a wine geek is fun.[/author_info] [/author]