Long considered the blue-collar workhorse of the winemaking process, operating sub rosa, yeasts have recently taken center stage in many conversations about wine and the desire to emphasize the expression of vineyard apart from human and technological influence. At the essence of the debate is the decision to inoculate with commercial yeast or to allow the ambient yeast from the grape skins, the vineyard and the winery environment to start the fermentation process “naturally.” Quite often the opposing philosophies square off like a pay-per-view fight card: Romantic vs. Realistic, Chance vs. Control, Variety vs. Consistency and Risk vs. Safety.

Some Facts About Yeasts & the Big Ferment

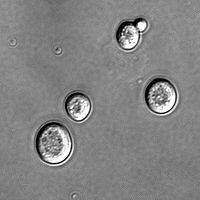

Yeasts are fungal micro-organisms which are responsible for the fermentation process of transforming sugar into alcohol when producing beverages such as beer and wine. There are many different types of wine-related yeasts. Those that are found on grapes and in highest quantity in the vineyards, like Hanseniaspora and Kloeckera, can often start fermentations; but due to their intolerance to alcohol (they falter at about 3-4%), they can’t finish the job. Species from the more well-known Saccharomyces genus will eventually take over to complete the fermentation because they can tolerate much higher levels of alcohol and out-compete other yeasts for nutrients.

Yeasts are fungal micro-organisms which are responsible for the fermentation process of transforming sugar into alcohol when producing beverages such as beer and wine. There are many different types of wine-related yeasts. Those that are found on grapes and in highest quantity in the vineyards, like Hanseniaspora and Kloeckera, can often start fermentations; but due to their intolerance to alcohol (they falter at about 3-4%), they can’t finish the job. Species from the more well-known Saccharomyces genus will eventually take over to complete the fermentation because they can tolerate much higher levels of alcohol and out-compete other yeasts for nutrients.

Of course, yeasts have been worker bees in winemaking for millennia, so what has changed? Start with the fact that wine today is a business. Many winemakers choose to inoculate their fermentations with commercial yeast strains to reduce the risk of “stuck” fermentations and develop a more consistent product, which helps protect the significant investment in their business.

Commercial yeasts are not synthetic, notes Tim Keller, a UC-Davis graduate and a winemaker of over 10 years currently consulting for Alta Ridge Vineyards in Sonoma. He says, “They are just selected from nature, grown and packaged into a format where they can be re-used.”

According to Karien O’Kennedy, a technical consultant from Anchor Yeast, the yeasts that wind up being produced commercially are picked precisely because of their ability to keep a fermentation going. Now we are getting closer to the crux of the current debate: Many people attribute rising levels of alcohol in modern-day wines to commercial yeasts, whose greater efficiency ensures that cuvées ferment completely. These yeasts “have been isolated from great natural ferments,” O’Kennedy explains. “Wines produced with commercial yeasts just often have higher alcohols because they are actually dry. Many natural ferments are not.”

An important point here: Yeast alone, commercial or native, cannot cause the higher alcohol levels in wine. From the biological perspective, final alcohol level is still driven by the sugar present in grapes at the time of harvest. When producers wait for more ripeness and pick at 28 Brix, which represents the sugar content in the berries, they can expect about 15% alcohol after fermentation to complete dryness.

Keller notes that winemakers are conscious of the their choice of yeast, just as they are of many other aspects of the vinification process. He says, “Selecting [commercial] yeast strains that can finish high-alcohol fermentations allows us to make a wine style that was never possible before.”

Wine as a Business: Big Market for Big Wines

Wine as a Business: Big Market for Big Wines

But who is really responsible for that “style,” which detractors of high-alcohol wines are apt to call “Parkerized?” Is it Robert Parker himself, and/or other gatekeepers who heap high scores on full-bodied wines. No doubt the debate has been intensified by subjectivity: one person’s “highly extracted” is another’s “over the top.” If consumers buy these wines—in essence creating demand for the style—shouldn’t wineries supply it?

This is where I think the true source of the divergence between these two schools of thought emanates. When someone decides to get into the wine business, he or she faces a fundamental decision to style wines toward the mass market, or to make wine of “terroir,” representative of its site, at the risk of appealing to a much smaller market.

Expression and Passion of Terroir

While there are many factors during the process of making wine that have an impact on the final product, natural ferments are considered to be one, if not the, top qualifier in holding what some call the “DNA” of the vintage. According to the noted author Alice Feiring, “using native yeast ferments is essential to a terroir-expressive wine.”

To be successful, the winery must possess very healthy grapes, grown in well-managed soil that has not been chemically farmed, followed by expertly clean winemaking. Indeed, the cliché “great wine starts in the vineyard” applies more pointedly than ever to the challenge of making wine naturally.

For some, the idea of natural wine does include a level of romance… of allowing the grapes to turn to wine practically by themselves with just a watchful, mothering touch along the way only intervening when absolutely necessary. “I am in for the game and the adventure and the passion and yes, the taste. I love wine. I love variety,” expresses Feiring.

Cory Cartwright, host of saignée, is adamant that he does not favor natural-yeast wines based on philosophic loyalties, but rather to enjoy what is in the glass. He explains, “Sometimes it can be sublime, sometimes it can be bad, but it is rarely ever boring or standard.”

It comes down to the personal preference and taste of the wine consumer once again, as it always should. But can the average wine consumer taste the difference in a natural wine? In a natural ferment, there will be more diverse fermentation dynamics due to the many yeast species that are coming from the vineyard and the winery as opposed to a ferment inoculated with a single strain. Studies at Kumeu River Wines in New Zealand, who naturally ferment all of their wines, identified upwards of eight different species present throughout their fermentations. Natural ferments will often occur at lower temperatures and take longer to finish, which allows yeast to increasingly facilitate the development of texture and finesse in the wine, which one might be able to detect by way of mouthfeel or unique esters.

It comes down to the personal preference and taste of the wine consumer once again, as it always should. But can the average wine consumer taste the difference in a natural wine? In a natural ferment, there will be more diverse fermentation dynamics due to the many yeast species that are coming from the vineyard and the winery as opposed to a ferment inoculated with a single strain. Studies at Kumeu River Wines in New Zealand, who naturally ferment all of their wines, identified upwards of eight different species present throughout their fermentations. Natural ferments will often occur at lower temperatures and take longer to finish, which allows yeast to increasingly facilitate the development of texture and finesse in the wine, which one might be able to detect by way of mouthfeel or unique esters.

Tim Keller believes that one should be able to taste a difference. However, Linda Bisson, professor of Viticulture & Enology at UC-Davis, disagrees, stating, “Most of the time they cannot [taste a difference] unless it has strong ‘off’ characters.” Alice Feiring thinks it’s easier to tell the difference in white wines, but in many cases it’s more about being able to identify what is not natural in the wine, as in, for example, a Verdejo seemingly manufactured to impart Sauvignon Blanc-type aromas. She knows people who “can put their nose in Nebbiolo and smell the typical laboratory yeast used from Piemonte.” Michael Brajkovich, winemaker at Kumeu River, acknowledges he has been able to “tell what [commercial] yeast was used in a fermentation, but could not distinguish the variety or vineyard” in those same wines.

How to Find Natural Wines

Unfortunately, there are no labeling laws requiring ingredients on the label, and even if a producer identifies their wine as being made from natural ferment or native yeast, there is no way to know that the native yeast wasn’t supplemented with some commercial yeast after fermentation started. So, it takes footwork by the consumer to find producers who are legit; following blogs that focus on natural wine can help identify wines that have been enjoyed.

In the end, I believe it is simply a matter of style and taste rather than of right vs. wrong. As wine lovers, we should be open to experience what raw flora can deliver and make our own decisions that further define our individual styles and tastes as well as advance intelligent conversation about differing wine styles. To each his own.

Recommendations

Favorite Natural Wine Producers of Cory Cartwright:

Natural Wines I have recently enjoyed:

2007 Edmeades Zinfandel Mendocino

2006 Yangarra Shiraz McLaren Vale Single Vineyard

2007 Kumeu River Hunting Hills Chardonnay

Ed Thralls is a Certified Specialist of Wine who is currently enrolled in the UC-Davis Winemaker’s Certificate Program and enjoys writing about wine, social media marketing and other musings at Wine Tonite!

Ed Thralls is a Certified Specialist of Wine who is currently enrolled in the UC-Davis Winemaker’s Certificate Program and enjoys writing about wine, social media marketing and other musings at Wine Tonite!