The last time wine safety really made the news was when, in 1985, some Austrian winemakers were found bulking up their wine with diethylene glycol. Used as an ingredient in some kinds of antifreeze, it added sweetness and body to wine, along with the potential for liver, kidney, and brain damage if drunk in sufficient quantity. Thanks be to Bacchus, no one reported illness or injury as a result of the deception; most adulterated wines contained far too little diethylene glycol to pose a serious threat to anyone. Even better, the incident spawned much more significant wine safety regulations, especially about what can legally be added to wine.

We still face food safety problems today from non-food substances being added to edibles – the Chinese milk scandal, in which melamine was added to milk to boost its “protein” content is a fine example – but, at least in the United States, our biggest fears are accidental contamination. From Salmonella-containing peanut butter to cantaloupes covered in Listeria, the new brand of food un-safety cause us a lot of anxiety.

So, have you ever thrown a skeptical glance at your wine? Here are four ways your wine could be poisoning you. Don’t worry; it’s almost certainly not.

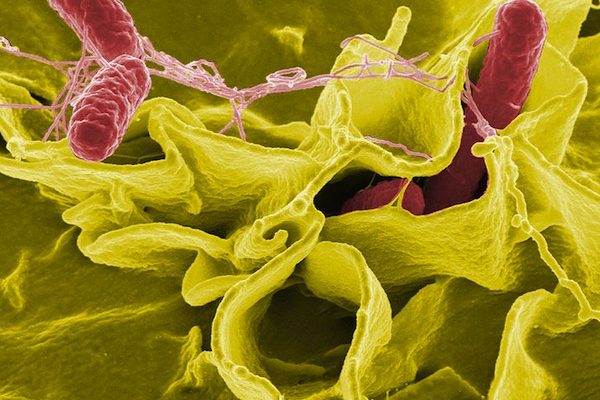

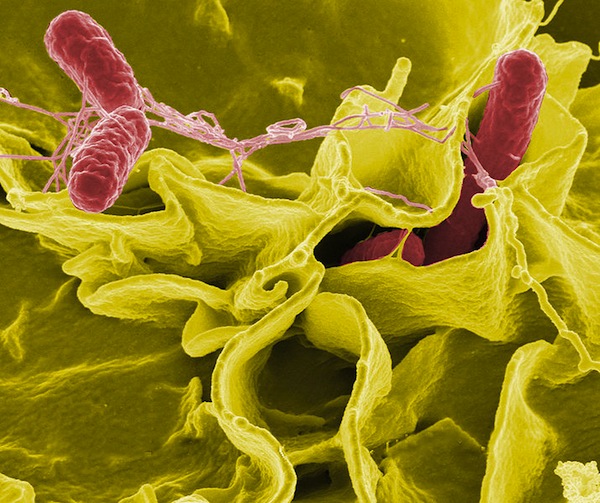

Foodborne illnesses

You’ve heard about cooking your meat, isolating your poultry, avoiding raw eggs, and washing your strawberries. There’s a reason why you’ve never seen a public service announcement about how to handle your wine properly: wine has never, as far as I can tell, been identified as the reason why someone became ill from a bacteria, virus, or parasite.

The Centers for Disease Control list Salmonella (bacteria), Toxoplasma (a parasite), Listeria (bacteria), and norovirus (virus) as the deadliest causes of foodborne illnesses in the United States. We have ample, strong evidence to say that wine is an antimicrobial and that wine marinades kill most (though not all) Salmonella on contaminated meat. Wine (together with garlic) appears to have something to do with why a popular wine-marinated Portuguese sausage made with raw pork called chouriço de vinho is safe to eat and not plagued with both Salmonella and Listeria. Whether Toxoplasma or norovirus can survive in wine is either an unexplored area or something too uninteresting to publish; either way, the absolute lack of scientific data on the subject says something: namely, it’s very likely not a big enough problem for anyone to care.

The bottom line: if you’re feeling squeamish at your fall community picnic, skip the potato salad and drink wine

Heavy metals

In 2001, a man in Australia gave himself lead poisoning by drinking wine made in a bathtub. The bathtub’s ceramic glaze was corroded, lead leached from the glaze into the wine, and from the wine into the man. That doesn’t happen every day. But even if your wine wasn’t made in a bathtub, it probably still contains some lead… and some arsenic, and possibly some cadmium and a few other dangerous metals. As far as the lead goes, so do your potatoes, your bread, yogurt, and beer, all of which rank near the top of sources of dietary lead according to a European Food Safety Authority study released last year. It gets there because lead is omnipresent in soil and absorbed by plants; we breathe it in the air and drink it in the water, too.

Enough to worry about? Probably not. Two studies in the past few years – one French, one Portuguese – say that the lead, arsenic, and other heavy metals in (French and Portuguese) wine are well within standard “tolerable weekly intakes” set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization. If you live in Greenland, arctic Canada, or another part of the world where seabirds make up a significant part of your diet, you have far more to worry about from lead shot residue in the game you eat.

A main problem here, though, is that we don’t actually know how much lead is safe. The WHO, the European Food Safety Authority, and the Centers for Disease Control concur that our current thresholds probably aren’t low enough and we don’t know how low they should be. We do know that lead has its worst effects on developing nervous systems – fetuses and small children.

The bottom line: if you’re pregnant or an infant, you probably shouldn’t drink wine every day.

BPA

Bisphenol A (BPA) has made a lot of news in the past decade: as a common ingredient in polycarbonate plastics including the liners used in some metal cans and, famously, some baby bottles. As an endocrine disruptor – a molecule that looks like and in some ways acts like a hormone (estrogen, in this case) in the body, BPA could, maybe, be causing mass havoc from cancer to obesity to early puberty. The US National Toxicology Program currently considers BPA of “some concern,” smack dab in the middle of its neglible-to-serious concern spectrum, though that estimate is more conservative than much of the public outcry.

BPA is ethanol soluble, and BPA is found in wine. Not all wine comes into contact with plastic, of course, but more of it does than you probably think. Beyond bag-in-box wine or bottles sealed with closures other than cork (either plastic cork-replacements or screwcaps lined with plastic), most commercial wine is fermented and/or stored in stainless steel tanks lined with a potentially BPA-containing epoxy resin. Scholle, the largest manufacturer of plastic bags for bag-in-box wine, released a statement back in 2008 that none of their products “contain or are made with BPA.” Representatives of Nomacorc, the largest manufacturer of synthetic closures, have made similar statements about their closures.

The biggest source of BPA in wine is almost certainly those epoxy resin liners in fermentation vats and storage tanks. Both the European Commission Scientific Committee on Food (in 2002) and the World Heath Organization (in 2010) have estimated that a medium-sized adult could ingest 0.11μg/kg (0.24μg/lb) of BPA a day, IF that adult drinks an entire 750mL bottle of wine and IF that wine was produced or stored in a vat with an imperfectly-applied epoxy resin liner. A more realistic estimate based on actual measured BPA values in wine, instead of worst-case scenarios, estimated that that hypothetical medium-sized person who drinks (again) an entire bottle of wine each day ingests less than 0.03μg/kg BPA per day. Compare that value with the estimated total BPA an average American adult takes in each day – about 0.18μg/kg, according to a moderate FDA analysis – and wine probably isn’t contributing much BPA to your diet if you’re drinking one or two glasses a day (at about 0.006μg/kg BPA per 5 oz glass).

The bottom line: if you’re concerned about your BPA intake, reducing your wine consumption is going to do a lot less for you than cutting canned foods out of your diet.

Ochratoxin A

Ochratoxin A (OTA) makes the news much, much less often than Salmonella or BPA, but its presence might be more of a threat to you and your wine-loving friends. OTA is a toxin produced by fungi (mostly Aspergillus and Penicillium species), carcinogenic in humans in high enough quantity, associated with liver and kidney tumors, and a serious health concern. It shows up in wine because when the right (or wrong) fungi grow on grapes in the vineyard, the toxins they produce can be carried over into the finished fermented product. OTA is an even more significant problem in beer, incidentally, because the toxin will leach out into wort made from barley or malt on which fungi grew during storage. The same goes for grain products like cold cereal, peanut butter (where moldy peanuts sometimes go to hide), raisins, coffee, chocolate, and spices.

OTA is most common in wines from relatively warm climates – the Mediterranean, Central California – where warm, sometimes humid vineyards provide a hospitable environment for fungal growth; just think about when and where you tend to see mold in your home. Different studies have come up with very different numbers about how many wines contain OTA – the highest estimates approach 50% (mostly from the Mediterranean; American wines tend to test low) – but studies concur that very, very few wines risk exposing drinkers to more than the WHO “provisional tolerable weekly intake.” WHO doesn’t think we should be concerned about ingesting less than 112ng/kg of OTA, and the most highly-contaminated wines don’t clock in far above 2ng/L, the maximum tolerable limit for OTA in wines produced or sold in the EU.

Even still, the wine community is taking OTA seriously. Multiple strategies are at work for reducing OTA levels: new fungicides, yeast biocontrol agents which outcompete dangerous fungi in the vineyard, fermentation yeasts which take up OTA and allow it to be eliminated with lees (dead yeast cells), and fining agents which simultaneously remove OTA and clarify wine, to name a few.

The bottom line: your cereal, peanut butter, and raisins are probably a bigger source of OTA in your diet than your wine.

There’s plenty to fear from what we eat and drink. I certainly haven’t mentioned every cause for wine-related health concerns – pesticides show up in wine, sulfites are a source of concern for some people, biogenic amines can give you a headache, and then there’s the alcohol itself. Moreover, a polysyllabic list of absolutely normal byproducts of fermentation – acetaldehyde and ethyl carbamate are two with higher profiles – have been named as potential carcinogens, with food scientists and microbiologists working on engineering microbes to make less of them in nearly every sort of fermented food from wine to bread to kimchi.

But, the bottom line? Drink on. Compared with the rest of what you eat, your wine is pretty safe.