Argentina is a place full of contrasts – if not contradiction. It is the wealth and bustle of Buenos Aires and the quiet, ramshackle villages of the interior. It is the vast desert plains of Mendoza, set in front of the majestic wall of the Andes mountains, a combination that drives the country’s winegrowing.

As far as wine is concerned, it is a place that insists on how its vineyards are spread along over 1200 miles, from North to South, and hundreds of meters of altitude, providing great diversity of growing conditions. However, it then sees most of its winemakers describing their wines in market-driven terms (entry-level, premium, super-premium, icon) and defining those categories by increasing use of oak. Argentina praises its terroir, but often seems to negate it through standardized winemaking practices that greatly reduce its contribution to the final product.

As far as wine is concerned, it is a place that insists on how its vineyards are spread along over 1200 miles, from North to South, and hundreds of meters of altitude, providing great diversity of growing conditions. However, it then sees most of its winemakers describing their wines in market-driven terms (entry-level, premium, super-premium, icon) and defining those categories by increasing use of oak. Argentina praises its terroir, but often seems to negate it through standardized winemaking practices that greatly reduce its contribution to the final product.

So what gives? Which is it, already? Diversity or commercial uniformity? Great terroir or just the right conditions to produce massive amounts of serviceable, commercial wines?

Churning out grapes and wines

There’s a bit of both, of course, although the large outfits churning out the majority of the country’s wines seem more centered on the serviceable and uniform. Just after I returned home from a trip to the country’s main winegrowing regions, in September, I wrote this post called “Visiting a Winery in Argentina: The Standard Version”, as a reaction to the repetitive nature of the discourse I had heard just too often.

Argentina is, no doubt, a great place to grow grapes – as far as the grape grower is concerned. There is plenty of sunshine, you turn the water (coming down from the Andes) on and off as desired and there is hardly any disease pressure. As a farmer, what’s not to like?

However, when it comes to making wine from those grapes, it’s a bit different. There is a lot of sun and heat – maybe too much, for all those vineyards in the flat plains of Mendoza or San Juan. In San Juan, north of Mendoza, most people will tell you it’s even too hot for malbec – even the syrah, which typically stands more heat, can come out very, very big. The fact that they also make white there could seem suprising, considering that.

However, when it comes to making wine from those grapes, it’s a bit different. There is a lot of sun and heat – maybe too much, for all those vineyards in the flat plains of Mendoza or San Juan. In San Juan, north of Mendoza, most people will tell you it’s even too hot for malbec – even the syrah, which typically stands more heat, can come out very, very big. The fact that they also make white there could seem suprising, considering that.

Acidifying musts – and significantly so – is routine, for most of the major wineries. Alejandro Nesman, the head winemaker at Piattelli Vineyards’ winery in Salta, the northern, “cool” region of Argentina, even said to us, without any hesitation: “It’s impossible to make wine in Argentina without acidifying.”

Maybe it’s just me, but if you’re saying that you always – emphasis on always – need to make adjustments to ensure that your grapes actually make good wine, you’re telling me you don’t have great terroir. What you have is a good place to reliably generate vast amounts of serviceable commercial wine – which is not a bad thing in itself, just not a great one.

I have to admit, a basic, not-too-oaky, ripe and full-bodied malbec is a great match for a grilled steak – as you inevitably discover on any trip to Argentina, where their (awesome) barbecue is a staple. As you go up into the reserve and grand reserve cuvees, however, things get more problematic as many wineries seem to think that “reserve” just means more oak, and not necessarily a better parcel or older wines or other factors that might better justify the term. Oddly enough, the problem seems to be the same as in Cahors, as I saw a few years ago on a visit for their own Malbec Days.

I have to admit, a basic, not-too-oaky, ripe and full-bodied malbec is a great match for a grilled steak – as you inevitably discover on any trip to Argentina, where their (awesome) barbecue is a staple. As you go up into the reserve and grand reserve cuvees, however, things get more problematic as many wineries seem to think that “reserve” just means more oak, and not necessarily a better parcel or older wines or other factors that might better justify the term. Oddly enough, the problem seems to be the same as in Cahors, as I saw a few years ago on a visit for their own Malbec Days.

On top of that, a number of wineries are rounding out the already very fruity, ripe malbec fruit with residual sugar, falling in line with a rather deplorable yet growing fashion embodied in US wines by the likes of Apothic and Ménage à Trois. Wineries like Trapiche, Piattelli and even Norton have gone on that trend, particularly in entry-level wines – something which felt to me like an unnecessary extra layer of frosting on an already pretty chocolatey cake.

Specificity, too

That being said, there is much more to Argentina than this mass of interchangeable, often oaky, soft and overpolished malbec. When winemakers look to match grape to place and to express the specifics of the various regions – the heat of San Juan, the bright sun of the heights of Salta, the relative cool of Patagonia – great things happen. Torrontes would be a case in point, as the variety is produced in every style, from a light, bright and “citric” profile, as they put it, to a highly aromatic, rich, and sometimes almost viscous texture.

One of my favourite encounters was with Jeff Mausbach and Alejandro Sejanovich, two long-time employees of local star Catena who set off on their own a couple of years ago to produce a whole range of site-specific, lightly-oaked and smartly-made wines. Mausbach had interesting praise for the Argentinian wine industry’s love of new oak: “Everybody wants to get rid of their oak barrels after three years, because they think they’re too old. That’s just when we start finding them interesting, and that means I can get a really good three year old Taransaud barrel for practically nothing.”

One of my favourite encounters was with Jeff Mausbach and Alejandro Sejanovich, two long-time employees of local star Catena who set off on their own a couple of years ago to produce a whole range of site-specific, lightly-oaked and smartly-made wines. Mausbach had interesting praise for the Argentinian wine industry’s love of new oak: “Everybody wants to get rid of their oak barrels after three years, because they think they’re too old. That’s just when we start finding them interesting, and that means I can get a really good three year old Taransaud barrel for practically nothing.”

Getting the older barrels helps Sejanovich make wines that express the specifics of sites – mostly selected in cooler areas in the heights of the Uco Valley, but also in Patagonia (for pinot noir) or Salta (for Torrontes). Their old vines malbec (Zaha, from the vineyard of the same name in San Carlos district of the Uco Valley, and TintoNegro 1955 Vineyard) have very distinctive structures, textures and aromatic profiles. Their pinot from a red clay soil in Patagonia also has tremendous personality, showing that when Argentine winemakers look for specific expression, they find it.

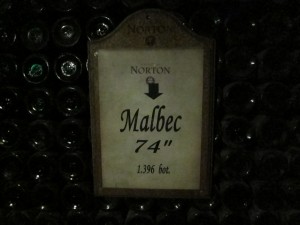

In that respect, there would be nice things to say about several other places. Like Finca Decero, who make well-defined, balanced wines, in particular a really delicious petit verdot, which I would be happy to drink any day. Norton, one of the biggest outfits in Argentina, also showed some site specific wines that had real character – and had us taste a 1974 Malbec that was fresh and bright, with a bright core of fruit under the layers of secondary and tertiary aromas from its almost forty years of aging. It was interesting to see how well it showed, having been made with none of the bigger-is-better ambition that has taken over the country’s cellars in the last two decades.

Out in Patagonia, Humberto Canale winery makes some wines that show the cooler climate of the area, including a very fine estate merlot that has great balance, with lovely spice and red fruit, and beautiful, fine tannins. (Canale was a contrast with some other Patagonian wineries who seemed to produce the exact same ripe and round thing as their colleagues from Mendoza, minimizing the distinctive character that can make Patagonia so great for pinot noir, as Manos Negras or Bodega Chacra show particularly well.)

Terroir, parcel by parcel

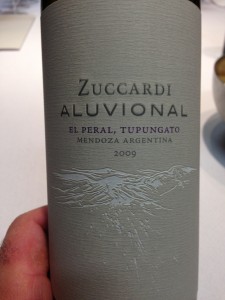

At Zuccardi Wines, a lot of work is being done in identifying the characteristics of every sub-region. Even though the winery produces, at one end, masses of simple, easy wines like Fuzion, it also has set a whole experimental winery, filled with concrete eggs, where small batches from different fields are produced under exactly similar conditions, in order to bring out the specifics of each parcel and variety.

For instance, four samples of malbec were shown, from different districts ans soils: one was highly floral, another mineral, yet another brimming with lovely dark fruit. And then, there were the three bonardas, including one that had almost bracing acidity, and a vibrancy and brightness that I would love to revisit in four or five years, to see how it would mellow out. That work gets embodied in “icon” bottlings like the Alluvional malbec (showcasing eponymous soils) or the Emma Zuccardi Bonarda, the latter being a showcase for the great things this wine could indeed bring to the Argentine wine portfolio, if all its potential is made to shine.

For instance, four samples of malbec were shown, from different districts ans soils: one was highly floral, another mineral, yet another brimming with lovely dark fruit. And then, there were the three bonardas, including one that had almost bracing acidity, and a vibrancy and brightness that I would love to revisit in four or five years, to see how it would mellow out. That work gets embodied in “icon” bottlings like the Alluvional malbec (showcasing eponymous soils) or the Emma Zuccardi Bonarda, the latter being a showcase for the great things this wine could indeed bring to the Argentine wine portfolio, if all its potential is made to shine.

Winemaker Ruben Ruffo, who is particularly dedicated to this project, clearly had tons to say about the various qualities of limestone, clay or gravel in the soil, and also remarked, encouragingly and smartly, that “what we do in these special projects brings out the specifics of each terroir, and it also informs what we do in all aspects of our range.” In other words, knowing the terroir helps make even the basic, million-case wines that much better and specific.

One should also point out the wines made by Bodega Colomé, whose vines are planted in the highest reaches of the Salta province, at altitudes ranging between 1,750 meters and a whopping 3,111 meters (over 10,000 feet!), the highest vineyards in the world. This means great thermal amplitude (the difference between day and night temperatures), as well as a powerful exposure to the sun. As you move up to the Reserva bottling, in this case, the wines grow darker and more intense, with big ripeness (up to 16% alcohol) but all that balanced by a significant acidity and the structure to back up the big fruit. There’s more oak in the bigger wines – but as opposed to too many other reserve bottlings, you hardly taste it. There is a true sense of terroir in the unique combination of heft and brightness you feel in there.

Finally, something should be said as well for Michel Rolland’s contributions to Argentinian wine, in places like San Pedro de Yacochuya and, even more, at Clos de Los Siete. In both places, it was interesting to reconsider Rolland’s style, so often defined as bluntly ripe and oaky, and emblematic of the excesses of modern winemaking. It was, in fact, quite an experience to taste three vintages of Clos de los Siete, the flagship wine made in that collective 800-hectare property created by several Bordeaux families in the cool heights of the southern Uco Valley’s Tupungato district. You couldn’t help notice how moderate the oak seemed, how elegant the fruit was, and how present the tannins were, as compared to so many other Argentine reds that show up as hypersoftened, oak-drowned and obviously acidified. “We never acidify”, Clos de los Siete vineyard manager Carlos Tizio Mayer said quite proudly. Just like Marcos Etchart had in Yacochuya, where Rolland has been consulting since he first came to Argentina in the late 80s, Tizio pointed out that the most famous of the flying winemakers really doesn’t look to add anything to wine, and is most happy with natural fermentations and no additions at all.

Finally, something should be said as well for Michel Rolland’s contributions to Argentinian wine, in places like San Pedro de Yacochuya and, even more, at Clos de Los Siete. In both places, it was interesting to reconsider Rolland’s style, so often defined as bluntly ripe and oaky, and emblematic of the excesses of modern winemaking. It was, in fact, quite an experience to taste three vintages of Clos de los Siete, the flagship wine made in that collective 800-hectare property created by several Bordeaux families in the cool heights of the southern Uco Valley’s Tupungato district. You couldn’t help notice how moderate the oak seemed, how elegant the fruit was, and how present the tannins were, as compared to so many other Argentine reds that show up as hypersoftened, oak-drowned and obviously acidified. “We never acidify”, Clos de los Siete vineyard manager Carlos Tizio Mayer said quite proudly. Just like Marcos Etchart had in Yacochuya, where Rolland has been consulting since he first came to Argentina in the late 80s, Tizio pointed out that the most famous of the flying winemakers really doesn’t look to add anything to wine, and is most happy with natural fermentations and no additions at all.

It was an interesting paradox, to hear Rolland praised for a natural bent and a will to express terroir, when you think that his love of ripeness and new oak is seen as largely responsible for so many formulaic malbecs – and formulaic wines all over the world. Could it be possible that many Argentine wineries copied Rolland’s “formula” from rather superficial impressions, as they aimed at conquering international markets? Like Argentinian wine, the answer to that question may be more complex and diverse than might seem at first glance.