Winemakers love to talk about “terroir expression” – a slippery phrase, but for me it readily translates into variety, regionality and interest. Small artisan producers often adopt and justify traditional, low intervention techniques to achieve that expression. For example:

- Wild yeasts produce more complex ferments

- Unfiltered wines are more vibrant

- Organically or biodynamically grown fruit shows its terroir more fully

Contentious statements? Hot air? I don’t believe so. But there’s one technique seemingly beloved of natural winemakers that leaves me cold. When it comes to making a wine that says anything about its origin or grape variety, whole-bunch fermentation and close cousins carbonic and semi-carbonic maceration sound the death knell.

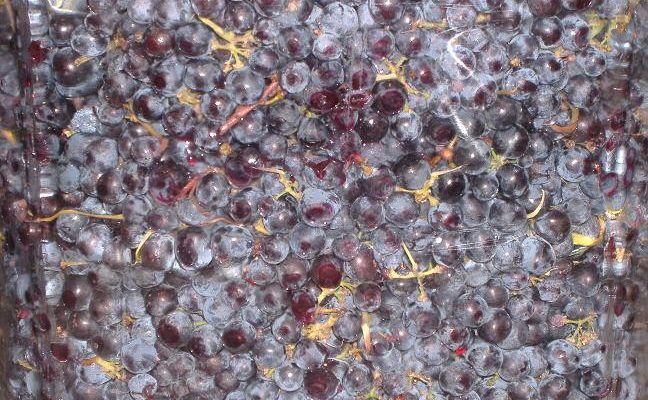

I won’t attempt a detailed technical description, when there are already so many good examples – like this one. But in short: true carbonic maceration requires carbon dioxide to be pumped into the fermentation vessel to remove oxygen, and aims to stop any conventional yeast-based fermentation occurring. Semi-carbonic/whole bunch is a hybrid process, where whole bunches of grapes at the bottom of the vessel start a conventional fermentation (they get squished by the weight, so that juice runs out, and fermentation begins with ambient yeasts). That naturally produces carbon dioxide, and the bunches above go through an intracellular fermentation as a result. This process is largely responsible for young Beaujolais’s typical flavours of banana, kirsch and bubblegum.

Why whole bunch?

Why are so many winemakers outside Beaujolais going down the whole bunch route? Well, it’s a great way of taming fiercesome tannins, and turning out a soft, easy drinking wine that can be cracked open just months after the harvest. And the fermentation can be completed in a mere 4 days. A cash-cow if you will. There’s nothing wrong with producers spreading the risk and ensuring they can earn a good crust, but I take issue with any distributor, retailer or wine educator who claims the resulting wine to be a marvelous expression of terroir – or representative of anything other than the winemaker’s need to get something on the shelves.

What about Beaujolais, I hear you cry – aren’t the illustrious wines of Morgon, Fleurie, Moulin-à-Vent et al. produced in exactly this manner? The answer is only a partial yes – First, the Beaujolais maceration traditionelle is very definitely in the semi-carbonic camp, avoiding the extremes of full carbonic maceration. Second, the more structured age-worthy Beaujolais crus not only have a significantly longer fermentation (Jean Foillard gives his Morgons 3-4 weeks), but frequently have some barrel aging as well. Structure and tannins are often prerequisites for long aging, and the great crus in Beaujolais can age for well over a decade.

Everything in its place

Context is all. I can enjoy the frivolity of the “whole-bunch style” in a young Gamay, but it is totally incongruous in a Tannat from the Madiran or a Grenache from Languedoc. If that sounds inflexible, ask yourself if you’d really want to drink a heavily oaked Cabernet Sauvignon from Alsace or a featherlight Pinot from Napa Valley? Regions do best when they play to their strengths and typicities, not just to a winemaker’s ego or the bank manager’s heart.

It worries me when winemakers talk about whole-bunch fermentation as if it were some kind of holy grail, to achieve even less intervention, to somehow take an even more hands-off approach and achieve a “truer” representation of their terroir. At least this was how Terroir al-limit‘s Dominik Huber expressed it.

This young, brilliant Priorat estate makes some sensational wines. Huber focuses on Carignan, which he feels is the best performer in this hot region. I wouldn’t disagree, but when he poured a barrel sample of a whole-bunch fermented Carignan (2013) with the remark “I may consider fermenting all my wines in this way in the future,” I was distraught. It had nothing of the region’s defining character, no tension and no backbone.

Huber is not alone, and I am in no sense singling him out. But this is an example of how the quest for less intervention, or more “naturalness” can sometimes be counterproductive. This isn’t the preamble for an anti-natural wines piece. I remain a diehard wild yeast nut. If I owned a car, the back window sticker would say “I brake for amphoras.” I believe filtration is the devil’s own work.

But please, if you have cabernet sauvignon, syrah, nebbiolo, xynomavro or any other strong-willed red variety growing in your vineyard, don’t dumb it down to a “nouveau” wine and let your terroir expression go up in smoke.