It’s no secret that the wine drunk in China is, overwhelmingly, red. Chinese tradition has it that red is a prosperous color. Red wines Some Chinese drinkers see red wine as having health benefits, good for the skin or for blood circulation. Wine consumption is often a social status-building move in China, and with few exceptions red wines (like red Bordeaux, infamously) rank higher on the prestige scales than whites.

But it’s old news that more and more of the Chinese wine market is about middle- and upper-middle class consumers looking for a pleasant beverage for home consumption China appears to be tilting toward a culture of middle-class wine drinking for enjoyment, not just ritual wine consumption by the business classes alone. A majority of middle-class Chinese wine shoppers are female, and women have historically (however unfortunately) been prime targets for marketing whites and rosés. From an aesthetic view – at least from a Western aesthetic view – whites and rosés pair better than reds with a lot of Chinese cuisine. And if “everyday bubbles” gave “drink pink” some competition for hip wine slogan of the year in 2015, “rosé isn’t just for summer” is still a regular wine media proclamation against decades of seasonally limited pink drinking. Rosé is big in wine. Wine is big in China. Surely it’s only a matter of time before everyone decides that rosé should be big in China.

But what kind of rosés do Chinese wine drinkers like? It’s not necessarily true that nationality affects wine preferences. As sensory science has become a more important part of wine marketing over the past decade, a number of studies have concluded that wine preferences hold a lot steadier across borders than you might expect. Nationality isn’t the thing, it seems, so much as habituation. People grow to prefer the styles of wines they see most often, and our general diet predisposes us to prefer some flavors over others. Australians, unsurprisingly, are a lot more comfortable with high-alcohol reds with bold black fruit and pepper flavors than are Chinese consumers, who prefer lighter, sweeter wines dominated by red fruit flavors according to an Australian study conducted a few years ago. Those big flavors may be an acquired taste, but the plentiful domestic shiraz market gives Australian drinkers plenty of opportunity to acquire it. Experienced tasters also tend to develop different preferences compared with novices, one of those obvious-sounding points that’s also been borne out in scientific testing. The steady pattern across all of these sensory studies is that every group of wine drinkers will contain multiple subgroups with different preferences, but the relative size of those groups varies. Sure, some Chinese drinkers will like peppery wines, and some veteran oenophiles will still prefer “beginner” wines, just not very many.

In other words, Chinese folk’s rosé preferences may lean in their own direction, but there’s little data on which direction that is. So, sensory scientists in Australia – whose third-largest wine market is China, and who’s beat only by France for foreign presence on Chinese wine shelves – are at work mapping out the unknown.

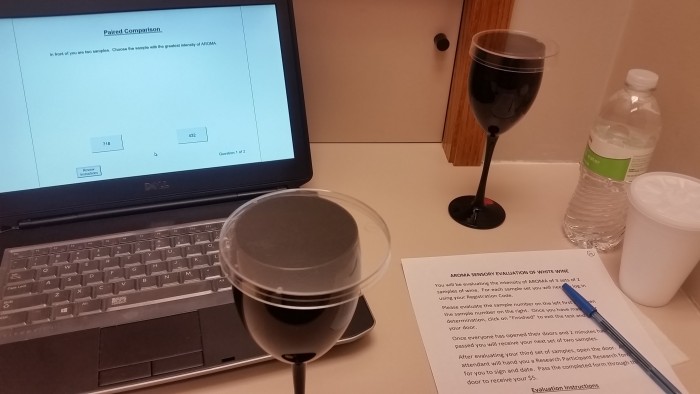

Australian scientists led sixty-two Chinese wine professionals through blinded testings for eighteen Australian rosés in about the US$7-35 range, plus two rosés from Provence and three from China. The tasters ranked those wines for total quality, expected price, and how much they liked them.

Australian scientists led sixty-two Chinese wine professionals through blinded testings for eighteen Australian rosés in about the US$7-35 range, plus two rosés from Provence and three from China. The tasters ranked those wines for total quality, expected price, and how much they liked them.

The Chinese wine experts preferred – and ranked as higher-quality, and expected to pay more for – rosés with “fruity, floral, honey and confectionery” notes, to use the formal, standardized terminology. They thought less highly of “citrus” and “yeasty” flavors, of “savoury, spicy, oaky, earthy, and leather” notes. “Red fruit” was better, herbal aromas were worse. The several savory, oaky, smoky wines in the line-up – Australian, French, and Chinese alike – didn’t fare well. Good acidity and high-intensity fruit bumped wines up on the perceived quality scale. All three of the Chinese wines, incidentally, were rated as being very different from each other, and one of the three fell consistently at the top end of the rankings while the other two were dealt middle-of-the-road scores.

The Chinese wine experts preferred less sweet rosés over sweeter wines, even though Chinese consumers seem to prefer sweeter red wines. The difference may be about expertise: experts have learned to appreciate many more of a wine’s characteristics, and unlearned the simple but unfashionable “sweet is good” equation. Something else to consider, though, is a lesson you’ll have learned first-hand if you’ve ever inadvertently mixed up your supply of semi-sweet eating chocolate with the unsweetened baking kind. Sugar tempers bitterness. Red wines, with their higher tannin quotients, can have a bitterness that (like dark chocolate) is very much an acquired taste; preferring reds with some residual sugar may be as much about not liking bitterness as about liking sweetness.

So formal sensory testing indicate that Australians and anyone else looking to open up a Chinese market niche for imported rosés should start with dry, red fruit-y, floral, honeyed pinks regardless of what grape variety they’re made from.

Why did we need science to figure that out? Maybe we didn’t. But here’s the thing: rank-ordering a large number of wines is one matter; identifying which characteristics are responsible for the rankings they receive is another. Science takes complex problems and makes them simpler until conclusions can be drawn about small, single pieces of the puzzle. Wine is complex. In this study, every taster was given a list of standardized tasting terms and asked to write their descriptions using only that list. But wine flavors are complex, and so those lists still have to be long and detailed if they’re going to be of any use. With all of those variables, figuring out which characteristics sit behind tasters’ wine preference ratings calls for some fairly fancy statistics, first to isolate individual characteristics, and then to put them back together again. Sensory scientists are well-practiced at fairly fancy statistics, on top of having protocols for choosing appropriate tasters and sample wines, and for standardizing tasting protocols themselves. Moreover, they ran chemical analyses on the wines that allowed for mapping sensory qualities the Chinese professionals like and didn’t like to associated molecules. A list of favored molecules may not do much to help a wine store stock shelves, but for the analytically-minded producers who have done so much to build the Australian wine empire, that sort of detailed chemical information adds a lot to “dialing in” new styles for new markets. Could this have been a marketing study instead of a sensory science study? Probably, except for the chemical analysis. Being published in a science journal instead of a marketing journal may have had as much to do with the difference as the content of the study. No matter; it’s science for having taken a complex problem and made it simple enough to find patterns amidst the complexity.

So, the latest sensory science research can say that Chinese wine professionals are likely to respond well to floral, fruity rosés, a simple response to a complex problem with lots of moving parts, made possible by carefully standardized methods. Now it’s up to rosé producers, and to marketers, to test the waters with uncontrolled wines and uncontrolled consumers, and to make things more complicated again.