How would Sherlock Holmes deal with wine crime? After all, the famous detective definitely appreciated fine wine. In the very first Holmes story (“The Sign of the Four”) he drank not only red burgundy from Beaune with lunch, but old Hungarian Tokay and three glasses of port after dinner, and he was always partial to port and white Burgundy. His encyclopedic knowledge of the subject was key to solving a couple of cases. So if Holmes were alive today (and not a fictional character), his pronounced proboscis would undoubtedly be sniffing around oenological misdeeds.

Wine crime has been around for ages. In Roman times Pliny the Elder complained that fraudulent amphorae of top wine – the equivalent of first-growth Bordeaux today – were being sold for consumption at Rome’s top tables. Wine fraud was so widespread in the Middle Ages that in Germany, the penalty for selling fraudulent wine ranged from branding to beating and even death by hanging.

Wine crime seems particularly rampant today. Most of it is out-and-out fraud, sparked by an explosion in demand for top wines and insane prices for rare bottles. However, wine crime has also included counterfeiting, arson, blackmail, and even murder.

But, although there has long been wine fiction (the best, IMHO, is Roald Dahl’s short story “Taste”), wine has not usually graced the True Crime sections of bookstores – until recently. Here are four fascinating books that delve into the dark side of the wine trade.

The Great Wall of Wine Crime

Much of today’s wine crime centers around China, where the demand for big-ticket wines set off a stunning price escalation, that in turn sparked some remarkable oenological fraud. If you want to know how things came to pass, the place to start is Suzanne Mustacich’s superbly researched and reported Thirsty Dragon: China’s Lust for Bordeaux and the Threat to the World’s Best Wines.

Until near the end of the 20th century, wine was not popular in China. Consumers preferred baiju, a fiery grain liquor. But at the 1996 National People’s Congress, Premier Li Peng raised a toast with red wine. He condemned excessive consumption of baiju and extolled the health and social benefits of wine. In a one-party state, that was considered an official imprimatur.

Chinese wine imports exploded by an astounding 26,000 percent in the first 11 years of the 21st century as it officially became okay to get rich in the Communist state. The Chinese elite saw wine – especially Bordeaux First Growths – as a sign of status, and bottles were often given as gifts or bribes. Chinese buyers scoured France for well-known wines and bought up lesser chateaux. But as Mustacich noted to a New Yorker interviewer, “enthusiasm for the concept of wine outpaced concrete knowledge” in China. They simply didn’t know what wine was supposed to taste like, so amateur fraudsters started refilling classic Bordeaux bottles with cheap plonk.

In 2008, the duty on wine imports to Hong Kong was slashed to zero, a move renowned wine critic Jancis Robinson calls “arguably the single most powerful development in the modern history of wine, with the possible exception of the unexpected turnaround of wine’s fortunes in the US as a direct result of CBS’s 60 Minutes program on the benefits of a Mediterranean diet in the 1990s.” On her website, she also noted that “Hong Kong overtook London and New York as a center for wine auctions, and never a month seems to go by without a major wine event or wine fair in Hong Kong, where the average quality of wine drunk seems so much higher than anywhere else in the world.” Simon Tam, now head of Christie’s auction house in China, commented, “In just 30 years, Hong Kong drinkers time-warped through Cognac, Liebfraumilch and today have arrived at Romanée-Conti.”

Once people found that there’s money in them there wines – BIG money in the collectors’ market – then it was only a manner of time before the more sophisticated con artists found a way to get a piece of the action.

The most stunning frauds were committed by two hucksters who operated separately but used similar methods: Hardy Rodenstock and Rudy Kurniawan. Each is the subject of different but converging books.

Fake Jeffersons

In The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine, Benjamin Wallace looks at Hardy Rodenstock, who pulled off one of the most spectacular wine frauds ever: fake bottles of wine purporting to have belonged to Thomas Jefferson.

On December 5, 1985, Christie’s auctioned off a bottle of supposed 1787 “Lafitte” (an old spelling) that had the letters “Th.J.” etched on it. The bottle had supposedly come from a rediscovered bricked-cellar in France. Christie’s wine chief Michael Broadbent certified the bottle and engraving as being the style of 18th century France. Other supposed Jefferson bottles were also on offer. After two minutes of intense bidding, the bottle sold to Christopher Forbes of the Forbes publishing family for £105,000, or about $157,000. In today’s dollars that would be about $355,600.

Billionaire Bill Koch, who has a collection of some 40,000 bottles, bought four other bottles of purported Jefferson wines, and later discovered that both his bottles and the Christie’s bottle came from German wine collector and music publisher Hardy Rodenstock. But somehow Koch, who loves getting his hands on prize bottles, was suspicious.

There are two ways to forge wine: tamper with what’s on the bottle, or tamper with what’s within.

With a good printer, you can forge labels. Proper old bottles are more difficult since they can vary widely. Koch looked into it and found that the “Th.J.” on his Jefferson bottles was made with a modern engraving tool like a dentist’s drill. It was a fake. Tangled legal actions ensued, and Wallace untangles the puzzle well. It is a great detective story, worthy of Holmes himself.

On the Dark Side

In “In Vino Duplicitas: The Rise and Fall of a Wine Forger Extraordinaire”, Peter Hellman details the extraordinary tale of a great palate that went over to the Dark Side. It is also a great mystery story and a good companion to Wallace’s book.

Indonesian-born Rudy Kurniawan was a renowned collector who was generous in sharing his gems with well-heeled collectors at parties and dinners. He was known as “Dr. Conti” because of his pronounced preference for Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, the stratospherically priced red Burgundy. He also consigned many lots to auction, especially at Acker Merrall & Condit.

But he, too, was peddling fakes — forgeries that netted him millions of dollars.

Tampering with contents is even more tricky than faking labels. If a wine is so old that you don’t know what it’s actually supposed to taste like, who is to know? Wine can vary significantly from bottle to bottle, even in the same vintage. Collectors may not have the experience or expertise to know if what they are tasting is genuine. Some bottles are so rare that there may be no one alive that knows what they are supposed to taste like. And there is a further complication; as Serena Sutcliffe of Sotheby’s told The New Yorker (with regard to Rodenstock), most wealthy collectors would rather not know about the fakes, or, if they do know, would rather not make it public.

This is where the actions of some auction houses such as Acker Merrall & Condit, Sotheby’s, and Christie’s, which are supposed to authenticate wines they sell, have caused controversy and earned the ire of some collectors like Bill Koch. In short, Koch claims, they did not do due diligence, auctioning off millions of dollars in fakes. Both Hellman and Wallace do an excellent job of laying out the role of the auction houses and their lapses, in the dual wine fraud scandals.

Koch pursued Kurniawan, too, after learning that much of the counterfeit wine he purchased at auction had been consigned by Kurniawan. It turns out that Rodenstock and Kurniawan both saved empty bottles of old wines to use in their bogus bottlings. Kurniawan hit upon the idea of buying up stocks of old négociant Burgundies for his blends. And he knew what the wine was supposed to taste like – or, at least, what his bacchanalian buddies thought it was supposed to taste like. Though there was no evidence he had any formal enological training, he demonstrated a savant-like acuity for tasting and identifying wines. Even after he was exposed as a fraudster, it was widely agreed that he had a hell of a discerning palate.

The forgeries managed to fool some of the most discriminating palates, which was extremely embarrassing to auction houses and resellers. One, their own experts were fooled by the bottle contents and the packaging, and, two, the experts were apparently unwilling to question too closely the provenance of some of the wines they were putting on the block, even when the wine producers themselves sounded alarms about fakes.

Kurniawan’s scam started to unravel when Laurent Ponsot, owner of Domaine Ponsot, noticed in a 2008 Acker auction catalog a bottle of rare 1929 Ponsot Clos de la Roche. Also included were 38 bottles of another Ponsot Grand Cru, Clos de Saint-Denis from 1945 through 1971. In fact, the Clos de La Roche was not produced under the Ponsot label until 1934, and the domain did not start making Clos Saint-Denis until the 1980s. All the bottles had come from Kurniawan.

Ponsot, like Koch, was outraged and determined to find the fraudster. When police raided Kurniawan’s Los Angeles home, they found hundreds of fake labels, old bottles, and blending equipment. In 2013 Kurniawan was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment for fraud. The scandal shook the auction houses to the core, and they started imposing more stringent standards and checks for accepting collectors’ consignments for sale.

Even arson has come into play in wine forgery.

Fired Up

In Tangled Vines: Greed, Murder, Obsession, and an Arsonist in the Vineyards of California, Frances Dinkelspiel spins a great tale that begins in the early days of California winemaking, when its center was not in northern California, but near Los Angeles.

In the early 21st century, a Sausalito photographer named Mark Anderson created a fake wine-storage boutique in which many restaurants and collectors consigned priceless collections. Anderson stole much of the wine and sold it off. Faced with both bankruptcy and discovery, Anderson set the Vallejo storage facility afire in 2005. Much of the valuable wine was gone, but some remained. Collectors who went to see what remained were astonished to open cases to find rare bottles replaced by bottles of “Two-Buck Chuck” and similar cheap wine.

Among the wines destroyed were 175 bottles of Port and Angelica from one of the oldest vineyards in California made by Frances Dinkelspiel’s great-great-grandfather, Isaias Hellman, in 1875 at Rancho Cucamonga.

Dinkelspiel weaves together the story of the rather pathetic Anderson with a narrative of the early, lesser-known days of the California wine industry, especially in Rancho Cucamonga east of Los Angeles, and in doing so has woven a compelling tale of murder and intrigue. She, too, touches on the seismic effect the Kurniawan scandal had on the close-knit world of fine wine, particularly the auction houses.

Tainted Roots

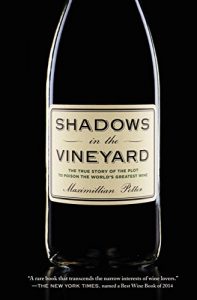

As villains like to say in books and movies, blackmail is such an ugly word. But even extortion has spread to the world of fine wine, as documented in Shadows in the Vineyard: The True Story of the Plot to Poison the World’s Greatest Wine by Maximillian Potter.

In 2010, Aubert de Villaine, owner of Burgundy’s inimitable Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, received a ransom note. The writer enclosed a detailed map of the vineyard and its rootstocks and threatened to poison the vines. As a sample, he killed off two vines using a poison-filled syringe and threatened to destroy more vines unless he was paid off.

Wines of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti fetch thousands of dollars on the open market and at auction, as well as on the black market. As noted earlier, this wine was one of Kurniawan’s favorite counterfeits. So de Villaine was not going to risk the domain’s reputation, so he immediately called in the French equivalent of the FBI.

Police, with de Villaine’s cooperation, set a trap for the blackmailer, who was caught as he tried to escape with the ransom money left in a cemetery in nearby Chambolle-Musigny. The blackmailer was a career criminal who decided to branch out into oenological extortion. He had targeted other vineyards in Burgundy as well. It’s a fine tale, and well-rendered by Potter.

Pass the port, will you, Watson?

Featured image by Office of Public Affairs.