It is a drizzly afternoon in late February when Stéphane Ogier drives me in his Range Rover to the top of a hillside overlooking the Rhône River and the small town of Seyssuel just north of Vienne.

We bump along rutted, muddy farm lanes at the edge of a plateau where a few vineyards interspersed among groves of trees start their descent down the hillside. We finally stop at a plot where a handful of sheep are grazing tender spring grasses emerging between the vines. From here, through the shifting mists, we can make out vineyards on a distant hill.

“That’s the northern vineyards of Côte-Rôtie,” Ogier says pointing to the rugged hillside on the opposite side of the river. Ogier is a handsome young man in his 30s dressed in jeans and a dark-plaid jacket. An in-vogue stubble creeps up his square French jaw toward where thick brown hair laps over his ears.

Ogier grew up on the other side of the river, in Ampuis, a little one-horse town where the horse is most likely out plowing in the vineyard but which is nevertheless home base to the famous red Syrah wines of Côte-Rôtie. Like many other teenage boys of Ampuis, Ogier worked in the family vineyards and winery. His father, Michel, had sold grapes to the Chapoutiers and the Guigals until 1980, when he began to make his own wines, sturdy red Syrahs that were soon considered to be among the best in the appellation. Now, Stéphane is gradually taking over the business and soon will be opening a new M & S Ogier winery and tourist tasting room in Ampuis.

But along the way, Ogier went slumming, falling in love with this east side of the river, a place which is viticulturally on the wrong side of tracks. No matter how attractive they are, grapes farmed here are without pedigree, unlike the proper vineyards Ogier grew up with.

As we continue along the road, Ogier points to older vineyards overgrown by trees and explains that it was not always so. Even though the left bank is now considered the “dark side” of the northern Rhône, the hills here and the ones overlooking Vienne to the south and Chasse-sur-Rhône to the north once produced quality wines back when Côte-Rôtie lacked the Parker-approved reputation it now enjoys and before the classifications of the 1930s began anointing certain wine regions as classic and others not. There are no appellations on the east side of the Rhône until you reach the exit for the Hermitages.

Ogier now wants to reverse this fact of history. He and a dozen other winegrowers have planted grapes or restored vineyards here, making “vin de pays” wine under the very unromantic label of “Collines Rhodaniennes IGP.” In France, where having proper wine parentage is all-important, a wine without appellation has difficulty finding a place on fine-wines shelves. Even in more democratic America, an IGP in a display lineup next to Côte-Rôties and Hermitages has difficulty attracting shoppers at a decent price without the intervention of a time-consuming hand sell by wine shop personnel.

Becoming an appellation and moving up through the ranks to a cru status is about as difficult in France as is getting an on-premise liquor license in Pennsylvania, but Ogier and his colleagues are determined to do it. It will take time, money and patience, and a few owners aren’t sure it’s the proper path. Nevertheless, they have taken the first step of applying to become a lowly “Côtes du Rhône” wine.

If successful, Seyssuel will become the northernmost Rhône village among the 171 other anonymous towns, mostly in the south, who have that status. There is a reason it will be the only CdR village locally; in a land where wines bear the labels of Côte-Rôtie, Condrieu and Château Grillet, being a CdR vineyard is about as appealing buying a boarded-up home in a fixer-upper neighborhood.

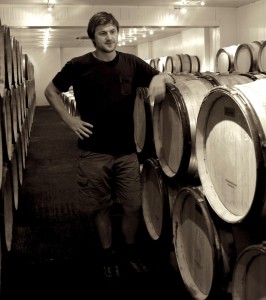

Back on the right bank, we pull up in front of Ogier’s impressive new winery on the south side of town, where the last of the terraced vineyards of Côte Brune are located across the road, and make our way through the mud and construction equipment to Ogier’s spacious new cellar. Wine thief in hand, Ogier goes scrambling among the barrels, and for the next half-hour we taste mostly 2014 barrel samples of various Ogier plots in Côte-Rôtie, then the Seyssuel.

I became curious about Seyssuel two years ago when I first tasted a wine from there, the M & S Ogier “L’Âme Soeur,” (“kindred spirit”) along with Ogier’s Côte-Rôtie, at a Robert Kacher portfolio tasting in New York. The Rôtie sells for about $100 a bottle, while L’Âme Soeur is about $70, commanding that much because of both Ogier’s and Kacher’s reputations, plus the fact it is excellent wine. I thought at the time, how can a Syrah taste this good without me having heard about the region?

I became curious about Seyssuel two years ago when I first tasted a wine from there, the M & S Ogier “L’Âme Soeur,” (“kindred spirit”) along with Ogier’s Côte-Rôtie, at a Robert Kacher portfolio tasting in New York. The Rôtie sells for about $100 a bottle, while L’Âme Soeur is about $70, commanding that much because of both Ogier’s and Kacher’s reputations, plus the fact it is excellent wine. I thought at the time, how can a Syrah taste this good without me having heard about the region?

Now, the 2014 sample that will become L’Âme Soeur tastes similar to the Côte-Rôtie samples with lots of fruit and underlying savory notes but perhaps with even more structure, and the evolving 2013 sample is even better. Ogier’s evaluation is probably accurate: “It’s not at the same level as my best Côte-Rôtie, but it is better than some of my Côte-Rôties.”

It is that expectation, along with the lure of expanded production on land less-expensive than Côte-Rôtie, that encouraged Ogier to plant his first vineyard in Seyssuel in 2001 and which encourages him to believe one day the area will rise step by step to become a recognized cru just like Rôtie, the Hermitages, Cornas and Saint-Joseph. He now has three separate plots on the east side, two hectares (5 acres) in total, and is getting ready to plant a third one. In a good year, he says he can get about 10,000 bottles of Seyssuel.

Ogier says that there are about 35 hectares (87 acres) planted in Syrah and a little Viognier (as is the practice in northern Rhône) under the collective Seyssuel umbrella in the hills above the three towns, producing about 100,000 bottles of wine. Currently, there are 13 growers (a 14th was expected to come on board some time in 2015), all but one from elsewhere.

“We are mostly established growers in Côte-Rôtie, Saint-Joseph, Cornas,” he says, the biggest name being the grower/négociant M. Chapoutier. Others include Louis Chèze, Pierre-Jean Villa, Yves Cuilleron, François Villard and Pierre Gaillard. Only one of the 13 actually makes wine in Seyssuel, Les Serrines d’Or, co-owned by Jérôme Ogier (unrelated to Stéphane). Everyone else picks the grapes and hauls them back to their respective wineries.

“The soil is all mica schist, but not exactly the same as on Côte Brune, where there is iron in the soil,” Ogier says. “There is still plenty of land to plant vineyards, although clearing it [of trees and brush] is expensive.” The land on the plateau, on the upward side of the muddy road we travel, has more loam, and Ogier dismisses it as “land for cereals, not vineyards.”

The Seyssuel producers put together their extensive dossier – history, soil profiles, standards of quality, and so on – and filed it with the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (still called the INAO) in May of 2013. If it is approved and added to the list of basic 171 Côtes du Rhône villages and counting, the next step would be to move up to the 95 villages that can be blended into Côtes du Rhône Villages wine, then join the 18 “named villages,” such as Visan and Roaix, that can actually put their names on the label. The final step would be advancing to cru, as such appellations as Gigondas and Vacqueyras have done before.

The Seyssuel producers put together their extensive dossier – history, soil profiles, standards of quality, and so on – and filed it with the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (still called the INAO) in May of 2013. If it is approved and added to the list of basic 171 Côtes du Rhône villages and counting, the next step would be to move up to the 95 villages that can be blended into Côtes du Rhône Villages wine, then join the 18 “named villages,” such as Visan and Roaix, that can actually put their names on the label. The final step would be advancing to cru, as such appellations as Gigondas and Vacqueyras have done before.

However, there are already complaints in the Rhône that 16 crus – the current number – is too many and diminishes the stature of such icons as Hermitage and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Some argue for two tiers of crus. (I hope to be around if and when that battle takes place.) Some winegrowers within the northern Rhône think the path that Ogier and his group are taking is too long, too costly, and too unlikely to succeed. They argue instead that a Rhône satellite status, such as Ventoux has, may be a better solution.

It should be mentioned, too, that Seyssuel is not the only IGP (née Vin de Pays) winemakers produce at both entry and quality wine levels. Next door to Côte-Rôtie is Condrieu, which produces white wine from viognier, and Ogier and others produce wines from grapes grown on the plateau above both appellations. The Ogier’s “La Rosine Viognier,” a Collines Rhodaniennes IGP, retails in the U.S. for about $40.

But Ogier and his Seyssuel colleagues are probably correct in choosing their strategy. After all, they are respected producers with pedigreed properties. They can afford to wait until the world – and the INAO – recognizes the beauty they have found on the wrong side of the Rhône.