While most classic wine regions of the Old World, such as Bordeaux, Rioja and Tuscany, focus on dry reds, the Rheingau, in Germany, is one of the very few classic regions producing primarily top-class white wines. These wines span sweetness levels from dry to off-dry to dessert. They are characterized both by finesse and power—the hallmark of great wines. The wines’ finesse comes from the riesling grape and their power is derived from excellent ripening conditions.

The Rheingau is situated near the town of Wiesbaden, southwest of Frankfurt. Its natural borders are the Rheinhessen to the south, the Nahe to the southwest and the Mittelrhein to the west. The Rheingau is one of the smallest wine-growing regions of Germany with only 3100 hectares planted to vines. Despite its modest area, the wines produced there are greatly esteemed. Excellent and long-lived Rieslings (85%) are made, backed by a rapidly rising percentage of fine Spätburgunders (10% and growing very fast). The latter is the same variety as the much celebrated French pinot noir but in Germany it ripens later than most other varieties; spätburgunder literally translates to ”late Burgundy”.

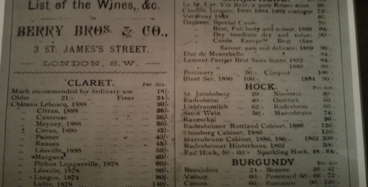

As one might expect, Benedictine and Cistercian monks—the ”usual suspects” of medieval wine history—also played their part in the Rheingau. During the 12th century they founded the Schloss Johannisberg and Kloster Eberbach monasteries and started making wine here. Some centuries later, Queen Victoria’s enthusiasm for Hochheim’s wines contributed to their popularity in England, where all Rhine wines were referred to as Hock. The Königin Victoriaberg vineyard was named after her, honoring her visit there in 1845.

Located close to the 49th parallel, the Rheingau enjoys a distinctly continental climate with cold winters and warm, but not hot, summers. Rainfall averages 500mm and even in summertime it can get quite chilly at night, with great daily temperature variations. Other major climatic influences are the Rhine River, which generally runs east to west resulting in warmer south and southwest exposures for nearby vineyards, and the Taunus mountains, which protect the region from cold northerly winds.

The typical landscape is picturesque with gentle rolling hills- less dramatic than Mosel region- which overlook the Rhine. Altitudes exceed 250 meters and maximum inclines are 60% on hillsides like Robert Weil’s Kiedrichers. The soil, which greatly influences the resulting wine style, varies from stony slate at the western part near the villages of Assmannshausen and Rudesheim to loess, sand and marl in the lower central villages of Geisenheim, Johannisberg, Winkel, Oestrich and Hattenheim. Soil reverts to stony phyllite in the higher central and eastern villages of Hallgarten, Kiedrich and Hochheim. In particular, wines from the lower slopes where the soil is heavier—sandy loam and loess—produce fuller wines, while at the higher slopes where it is more stony and slatey, the wines reflect more minerality, elegance and concentration.

The typical landscape is picturesque with gentle rolling hills- less dramatic than Mosel region- which overlook the Rhine. Altitudes exceed 250 meters and maximum inclines are 60% on hillsides like Robert Weil’s Kiedrichers. The soil, which greatly influences the resulting wine style, varies from stony slate at the western part near the villages of Assmannshausen and Rudesheim to loess, sand and marl in the lower central villages of Geisenheim, Johannisberg, Winkel, Oestrich and Hattenheim. Soil reverts to stony phyllite in the higher central and eastern villages of Hallgarten, Kiedrich and Hochheim. In particular, wines from the lower slopes where the soil is heavier—sandy loam and loess—produce fuller wines, while at the higher slopes where it is more stony and slatey, the wines reflect more minerality, elegance and concentration.

The Rheingau’s wines can be considered perfect examples of great terroir expression. Their style is unique and easily identifiable with peachy, citrus ripeness and intense stony minerality. Sometimes the wines can be austere and tight, usually with an almost phenolic texture. They tend to be medium- to full-bodied, and the majority are dry or off-dry. These wines can be easily identified in contrast to the elegant and floral versions from the Mosel, those from the Nahe and Rheinhessen areas which are riper and full of tropical fruits, or the fatter, even sometimes buttery, wines from the Pfaltz. Just like in Burgundy, the cradle of terroir, each specific site or vineyard is of great importance, creating the signature of the wine and also providing an indication of quality on (otherwise chaotic) German wine labels that seem to reveal everything and nothing at the same time—more about this later.

For Spätburgunder, the best sites lie in opposite geographical directions: in the west, the stony soils of Assmannshausen Höllenberg and in the east, the less celebrated calcareous soils of Hochheimer Reichstal and Stein. For Rieslings, on the other hand, the top expressions (from west to east in each case) come from Berg Schlossberg and Berg Rottland in Rudesheim, Klauserweg and Rothenberg in Geisenheim followed by Holle and Schloss Johannisberg in Johannisberg and Jesuitgarden in Winkel.

Next in line are Nussbrunnen and Marcobrunn in Hattenheim and Erbach respectively. The latter is situated very close to the river, mostly with marly soils, resulting in an opulent and full-flavoured wine character. But perhaps the most recognized vineyard is situated in the town of Kiedrich; it is the Grafenberg, with its famous stony phyllitic soil credited for giving spiciness and minerality to the wines.

During 19th and part of the 20th centuries, the wines of Rheingau, especially from sites like Marcobrunn and Steinberg, commanded very high prices, comparable to best and most expensive Bordeaux growths. Nowadays these wines are more reasonably priced. They offer excellent value at present, but prices are on the rise again, as the wines continue to show very high quality. However, these wines suffer from the same ”disease” as the rest of Germany’s: mainly labeling.

Labeling Problems

Residual Sugars. This is a major issue for the consumer, since there is no way to know exactly how sweet or dry a wine is. Yes, there is a rough guide for trocken and halbtrocken wines with the former having up to 9 grams/liter residual sugar and the latter up to 18g/l. But at the same time feinherb wines -more fashionable than halbtrocken, perhaps because feinherb sounds better- can have up to 50 g/l. Even the top quality dry wines -called Erstes Gewachs – may have up to 13 g/l and are considered, of course, dry. Furthermore there are wines simply labelled Kabinett or Spätlese, with no trocken or halbtrocken on the label, where sugars may easily reach up to 80 or 110 g/l respectively. There is no way to know, unless you happen to be clairvoyant, or take a really close look at the alcohol level. Less alcohol indicates more residual sugars but, again, there is no way to know exactly how much, unless you have researched the wine’s potential alcohol. Say for example, that the label simply states Spätlese without mentioning trocken or halbtrocken. In this case the sugars are higher than 18 g/l, but how much higher depends upon the grapes’ ripeness. If the alcohol is 7% and the producer picked at 10% potential alcohol then the amount is the difference in the alcohol measurements multiplied by 17.

Distinguishing the various sites. You simply cannot tell from the label unless you are a connoisseur and you are able to tell your Marcobrunn from your Honigberg or your Grafenberg from your Klostenberg. Erstes Gewachs on the label indicates a first growth site, like Marcobrunn and Grafenberg, but only if the wine has less than 13g/l residual sugar. If it has more, it may be labelled Erste Lage. Confusing again. (I totally agree with Hugh Johnson’s point that you must have a chair at Oxford University in order to teach German labelling!)

Classification of quality based on sugar ripeness. It is very understandable that in a cool climate country like Germany the crucial point is to have ripe grapes, but in my humble opinion this doesn’t mean a priori that a Spätlese (where the grapes have been harvested later) is a better wine than a Kabinett.

Although the above mentioned issues create difficulties—especially for an ordinary consumer—both in choosing a wine and in pairing it with food, there are ways to overcome these problems. First, by trusting a good – or even better, a great producer- like Robert Weil, Kunstler or Breuer. Second, by memorizing the best sites. And finally, by taking a close look at the alcohol level, as mentioned above.

Nevertheless, the amazing thing about Rheingau wines is their lovely balance of sugars, acidity and extraction, as well as the different wine styles that emerge, depending on producer profile and individual terroir. I personally think that despite the ‘label situation,’ the point is that you should be open to discovering and appreciating any given wine, rather than needing to everything about the wine before tasting it.

Ioannis grew up in Athens and at the age of 22 graduated from the Hellenic Naval Academy as Ensign. During his 21 year career, he met numerous challenges in various warships, however the greater challenge met, was flying Agusta Bell navy helicopters as pilot and instructor. Life’s ”true compass” eventually led him to the wine world. He holds the WSET Diploma with Merit and he recently joined the MW course. He recently became the father of a tireless son

Ioannis grew up in Athens and at the age of 22 graduated from the Hellenic Naval Academy as Ensign. During his 21 year career, he met numerous challenges in various warships, however the greater challenge met, was flying Agusta Bell navy helicopters as pilot and instructor. Life’s ”true compass” eventually led him to the wine world. He holds the WSET Diploma with Merit and he recently joined the MW course. He recently became the father of a tireless son