If someone in New York wants a bottle of Finger Lakes Riesling they can’t buy it in a grocery store. If someone in Pennsylvania wants to buy a bottle of Chambourcin they have to go to a state-owned retailer. A Texan who lives in Houston can buy wine anywhere in the city; a Texan who lives in Dallas is limited to less than half of the city.

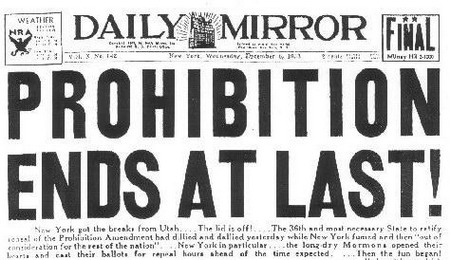

Welcome to the wonders of the three-tier system, which is the system by which beer, wine, and spirits are distributed in the United States. More broadly, “three-tier” is the shorthand description for the legal framework that has regulated alcohol sales in U.S. And if it seems odd, disjointed, frustrating, don’t worry. It does to most people.

“One of the reasons why I enjoy my work so much is the affect alcohol has had on American history,” says Richard Blau, a Tampa-area attorney who is considered one of the country’s leading authorities on the subject. One of his favorite anecdotes: that the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock because they had run out of beer.

The cornerstone of the three-tier system is the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition and specifically gave the states the authority to regulate alcohol sales any way the states wanted to do it. The 21st Amendment states, in Section Two:

The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

This has resulted in 50 laws in 50 states. Some states regulate pricing. Some states limit liquor licenses. Some states mandate dry areas unless voters petition for a change. Some states allow direct shipping, while others forbid it—even within the state. It’s so confusing that Wine.com, the leading Internet retailer, only sells wine in some three dozen states.

The only consistency, really, is the three-tier system, which exists in some form in every state. In the three-tier system, consumers (with some exceptions) must buy wine from retailers (or restaurants), who must buy from wholesale distributors, who buy from the producers. Retailers can’t buy direct from the winery and consumers mostly can’t either. Say what you will about the system, says Blau, but in 1933, when state officials were looking for a way to regulate alcohol after Prohibition, it was the best thing they could find. And, since then, it has done what they wanted it to do—made it easier to collect taxes, to regulate alcohol sales, and to prevent the corruption and abuses that existed between manufacturers and retailers before and during Prohibition.

(The ability of individual states to pass and enforce their own liquor laws was really a compromise negotiated into the language of the 21st Amendment, assuring temperant, or “dry,” states that they could remain so while allowing for the repeal of the 18th Amendment. The language was later used to defend the three-tier system, created for the reasons noted above, against Commerce Clause challenges.)

But that was 75 years ago. Why are we still using the three-tier system today? Generally, you’ll hear three reasons:

-

The states don’t want to give up the ability to collect taxes efficiently and easily. It would be much more difficult, says this argument, to get payment from out-of-state manufacturers.

-

Alcohol still needs to be controlled, from both a moral and legal standpoint. In this view, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which advocates tougher liquor laws, is the offspring of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was influential in passing Prohibition. And state governments still see a need for three tiers, which offers them an extra tier in which to regulate alcohol.

-

The system works best for those who have the greatest financial stake in it—independent retailers, the distributors who sell wine to all retailers, and the legislators who write the laws and get campaign contributions from the first two groups. So why would they want to change it?

Is one of these reasons more true than the other? Or are there other reasons? It almost doesn’t matter. Even if the three-tier system seems antiquated by the standards of the 21st century, it’s a legally protected antique. Save for the Supreme Court’s Granholm decision in 2005, which loosened state regulation of direct shipping, the Court has consistently ruled in seven decades of cases that when the 21st Amendment says states can do whatever they want, it really means they can do whatever they want.

As recently as 1966, in Seagram & Sons v. Hostetter, the Court said that the 21st Amendment “bestowed upon the States broad regulatory power over the liquor sales within their territories.” Even in Granholm, which was seen at the time as a great victory over the 21st Amendment and has seemed less so since, the ruling majority never disputed that the 21st Amendment’s grant of authority to the states. They just took exception to one small part of it.

Not even Costco could change the system. The giant retailer sued the state of Washington in 2004, arguing that the state’s regulatory system, based on three-tier, was anti-competitive and violated federal law designed to limit monopolies. Costco won at the district court level, but a federal appeals court overturned that ruling, citing the 21st Amendment.

So where does that leave the three-tier system today? Pretty much where it has always been, say a number of people on both sides of the issue. Groups like Free The Grapes are working at the state and federal levels to loosen three-tier in regards to direct shipping, but have had mixed success. One case working its way to the Supreme Court, in which retailers supported by The Specialty Wine Retailers Association want to use Granholm to allow them to sell across state lines, may not be as successful, says Blau. The states, stung by their loss in Granholm, have regrouped and refocused their efforts to protect their rights, and may even get the court to reverse part of Granholm.

That puts the burden on state legislatures, which have been reluctant to change the status quo. New York, despite a multi-billion dollar fiscal crisis, this year again rejected wine and beer sales in grocery stores. In Tennessee, a panel formed to study the state’s alcohol control laws says it’s in no hurry to make changes.

Which means we’ll just have to get used to buying wine the same way we always have.

— Jeff Siegel writes the Wine Curmudgeon blog, is the wine writer for Advocate magazines in Dallas and the Star-Telegram newspaper in Fort Worth, Texas, and freelances about wine for a variety of regional and national magazines. His philosophy is simple: The wine industry tries to intimidate consumers instead of educating them—and nuts to that. Wine should be fun, not intimidating.