Epicurus would not have given a damn about “how to cook your Thanksgiving turkey like a Peking duck.” He would have found the prices and boasting vulgar if he could see the menu (95 euros for macaroni stuffed with truffles and duck foie gras) at Epicure restaurant in Paris. He might initially be thrilled to find that his name is in the Merriam-Webster dictionary; he would quickly be disappointed to find they define his very purpose incorrectly.

Let’s start with this: real Epicureanism is not hedonism as we know it.

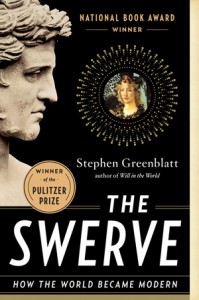

Merriam-Webster marks the year 1565 as the first time that “epicurean” became synonymous with “hedonistic.” Harvard scholar and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Stephen Greenblatt told me that’s no surprise.

“We’re doing an ancient disservice to Epicurus,” Greenblatt said. “Precisely as a way to undermine the impact of Epicurean philosophy, people a very long time ago already would say that, ‘Well, Epicureans are just hedonists. They believe that the life of a happy pig is superior to the life of Socrates.’ It happens not to correspond to anything we know about the actual lives or the ambitions of the people we’re talking about — of Epicurus and Lucretius and all of their followers.”

Greenblatt would know. His magnificent book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern chronicles the disappearance and rediscovery of one of the most significant works of literature ever created: Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, translated as “On the Nature of Things.” Lucretius was a Roman in the first century BC who followed the Epicurean school of thought closely. Epicurus was a Greek who lived 200 years earlier. Lucretius built upon the Epicurean ideals in his didactic poem that, Greenblatt explains, happened to help spark the Renaissance when an Italian nobleman discovered it, collecting dust on the shelf of a German monastery in 1417. Lucky him; lucky us.

So how did we get here? How did we end up with countless restaurants named after Epicurus? How did we wind up with an app (wouldn’t you love to explain apps to Epicurus and Lucretius?) named after the man, downloaded by tens of thousands?

It comes down to a fork, and we’re not talking about a forkful of caviar. We’re talking about an unfortunate fork in the road of history.

Epicurus grew tired of hearing his countrymen tremble every time a thunderstorm passed through. They would point to imagined gods on mountaintops, directing the meteorological traffic. He witnessed a society marked too often by poverty and suffering, and even more often by men who accumulated massive amounts of power.

And so Epicurus constructed his worldview around simple but vital ideas. He believed in atoms, still a controversial and unproven idea. He turned to scientific explanations and left the gods behind. He said that life’s purpose was ataraxia – a world without physical war, and a mind without strife and fear. He taught that pleasure should be every man’s goal, and here is where the distortion begins.

For Epicurus, pleasure is defined by the absence of pain and suffering. In fact, he declared pleasure and pain to be the very measure of good and evil, and he preferred a lifestyle that would promote the most pleasure for the most people. In his famous garden, he welcomed strangers and friends alike, but the results were hardly the stuff of modern tabloid legends. Greenblatt writes that Epicurus would serve “barley gruel and water.” I couldn’t find barley gruel on any menus in modern restaurants bearing Epicurus’s name.

This is not to say that Epicurus never enjoyed nice meals. He occasionally wrote playful letters to friends, asking them to bring good cheese. He felt that a long meal shared by friends was far more valuable than expensive material goods, or meals dominated by the most expensive foods and wines. He apparently loved to sit around what is now the kitchen table, because that was the hub of conversation and debate.

“Epicurus was not an extreme ascetic,” Greenblatt explained. “He thought that sex, good cheese, nice wine – these were all pleasant things in life. He just didn’t think that you should focus on them as the very center of what matters to you as a human being. Happiness in life depends upon savoring your being, enjoying being alive, but happiness can not depend on having the latest brand of X or Y, because inevitably you’re going to be disappointed.”

Women were part of Epicurus’ school, his garden. That alone was new and controversial, and it marked him for criticism. Those critics would claim that Epicurus was using women for the purpose of orgies. They claimed, famously, that Epicurus vomited twice daily as a result of his over-imbibing. Too bad establishing the truth requires more effort than believing rumor. Back to Greenblatt:

“On the contrary, they were – as far as we know – disciplined people, precisely because they thought that, for happiness, you shouldn’t have to depend on an unending supply on the best wines and beautiful black truffles.”

And here again is the key to understanding why Epicurus, were he alive today, would likely ask that most restaurants remove his name. Greenblatt elaborated, “Those foods and wines are only available to a small number of people, and Epicureans thought that happiness should be available to as many people as possible. They thought that pleasure should be the goal of life, but pleasure can’t be something that’s given only by a tiny number of objects to a tiny number of people that can afford them.”

Despite his controversial ideas, Epicurus lived a rather unbothered and happy life himself, eventually dying of “an excruciating obstruction of his urinary tract.” Did he denounce his ideals and turn to prayer? Quite the opposite; he told his followers that he quelled the pain with memories of good times and stimulating conversation.

By the time Lucretius was walking the streets of Rome, Epicurean philosophy had reached more than a cult following. It wasn’t mainstream, nor was it odd and marginalized. Lucretius’ masterwork drew the praise of his contemporaries, even those who didn’t adhere to an Epicurean worldview. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD 79, it buried and preserved a mountainside villa that included a library with nearly 2,000 rolls of papyrus. Many were associated with the philosopher Philodemus, an ardent Epicurean.

This was a fascinating moment for mankind. The Greeks and Romans seemed ready to finally shed their embrace of the gods; Christianity was in its nascency, hardly assured of prominence. Yes, there have been thousands of religions, but this window of time seemed to offer a way toward science, toward earthly ideals. Epicurus and Lucretius were leading the way.

Instead, Christianity ascended, and its leaders viewed the ideas of Epicurus and Lucretius as dangerous. Condescension toward Epicureans only intensified; how better to cut down a school of thought than to claim it is based in excess, in nearly pornographic views of sex and food and drink. Worse, it was labeled as selfish, a bitter irony; Epicurus grounded his teachings in valuing others.

As Professor Greenblatt notes in The Swerve, we’re fortunate to have any access to Epicurus and Lucretius. They could easily have vanished into the ages. There’s no reason to think we’re missing more of Lucretius’ work, but we only have a few full versions of Epicurus’ dozens. Thankfully, it’s enough to understand his teachings.

Here are some ideas in Epicurus’ own words, courtesy of Epicurus.info:

“What cannot be satisfied is not a man’s belly, as men think, but rather his false idea about the unending filling of his belly.”

“Do not spoil what you have by desiring what you have not; but remember that what you now have was once among the things only hoped for.”

“Nothing is ever good enough for someone who regards enough as insufficient.”

“Poverty, if measured by the natural purpose of life, is great wealth; but wealth, if not limited, is great poverty.”

“Since the attainment of riches can rarely be accomplished without servitude to crowds or sovereigns, a free life cannot obtain much wealth, but such a life has all necessities in unfailing supply. Should such a life happen to fall upon great wealth, this too it can share as to gain the good will of those about.”

These are not cherry-picked quotations to prove a point. I could add many more. Epicurus would simply not feel at home in a Parisian joint with three Michelin stars, no matter how much the owners tried to praise him.

The greater injustice is to ourselves. We ignore or misunderstand Epicurus’ works at our own peril. His ideas on science, the natural world, and death are stunning even today. To consider them in the context of the world 2,300 years ago? Difficult to comprehend. Epicurus is every bit the trailblazer whose path is now walked by the likes of Stephen Hawking and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

But back to hedonism. It’s time to change our vocabulary. Some argue that a word acquires new meaning when a population commonly understands the intent. That’s fine in most cases, but not this one. By minimizing Epicurus, by treating his powerful philosophy as nothing more than a pursuit of a better recipe or a cult restaurant or a monument to excess, we’re committing a crime of ideas. Just about every modern invocation of Epicurus is wrong, and it’s obscured the full scope of his important work. It’s handed a victory to his critics who spent hundreds of years trying to assassinate his reputation. We’re doing the work for them.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I must return to my book writing. My first, you might know, was published by Sterling. Well, by their branch that covers food and alcohol. They call it Sterling Epicure.