“How about a drink?”

“Yes please, a Spritz!” is the response of 100% of the students in the ancient university city of Padua, in northern Italy.

The Spritz is in fact the favorite drink not only of the young people from here in the Veneto region, but also of many people in Italy, especially in the north. Here it is considered a popular ritual celebrated just before lunch, or late in the afternoon, before dinner. For the youth, furthermore, the Spritz is more than a pleasant aperitif: it is a ritual, a tradition, a wonderful way to hang out with friends.

Every city or town in this part of Italy—and almost every wine bar—has its own formula for making a Spritz:

- in the Veneto it is always made with Prosecco (sparkling wine) with a slightly bitter mixer like Aperol

- in Vicenza you can find a drink called rabaltà: red wine mixed with orange soda like Fanta

- in Venice people prefer to mix water, sparkling wine and Select (a dark, bitter liqueur)

- in Padua, people ask for a spritz made with Cynar, famous Italian bitter liqueur made from 13 herbs and plants

- in Trieste and Udine (in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region), they have a still version of the Spritz—with dry white wine

- in the Trentino region, where they make their own classic method sparkling wines, consumers replace Prosecco with Ferrari sparkling wine

- in parts of South Tyrol the Spritz is served as a still (non-sparkling) drink; if they make it with a bitter liqueur it’s called a “Venetian”

- in Brescia it changes its name to Pirlo! (pronounced peerlou)

The Spritz can be also made with Campari, but this is a recent innovation; more alcoholic than Aperol, this bitter drink is easier to imitate. But not all these Campari-like drinks are of high quality, so often (to mask their mediocre taste) some bartenders add other spirits like gin.

Anyway, in order to call it Spritz, the drink must be made with this formula:

- 40% white sparkling wine (such as Prosecco)

- 30% sparkling water or seltzer

- 30% other alcoholic mixers, mainly red or orange, such as Campari, Aperol or Select

What is the origin of the Spritz? Nobody knows for sure. But mixing drinks has deep, ancient roots in Europe.

In ancient Greece, the symposiarch was not only the master of a party, but also the person charged with establishing what to drink—the correct mixture water and wine—and where. In Italy, the Romans drank mulled wine mixed with honey and spices—and even sea water sometimes. This custom then became widespread in conquered countries like Gallia (France) and Britain.

During the time of the Serenissima Republic of Venice, a privileged class called arsenalotti worked in the important Arsenal of Venice. These men benefited from preferential economic treatment, and in mid-afternoon they enjoyed a break from work with bread and red wine in the winter season, and biscuits and glasses of wine diluted with fresh water during the summer months. Very likely this was the ancestor of the Spritz.

The name itself seems to come from the German verb spritzen, to spray. During the period when Austrian governed northern Italy—which lasted more than a century, from the 1700s to almost the end of the 1800s—the Austrian soldiers in the Veneto and in Friuli frequented local taverns to drink wine. However, the powerful wines of Veneto and Friuli were too alcoholic for their tastes, as they were accustomed to the lighter wines of Austria. Hence the request to spray a bit (of water) into their glasses of wine.

Thus the original Spritz was composed of sparkling white or red wine, diluted with fresh water. In subsequent years, this custom spread throughout northern Italy, and colored variants were introduced: red like Aperol or Campari, or black like China Martini and Cynar.

Nowadays, the Spritz is prepared by mixing the base of Prosecco and soda water with a bit of Campari or Aperol (the most popular), or sometimes with Select, Cynar, or another similar liqueur, then adding a slice of lemon or orange, or an olive, and ice cubes.

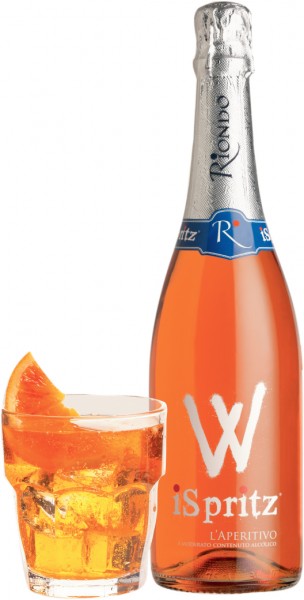

As noted, for the youth of northeastern Italy the Spritz is a ritual, an excuse to go out and be with friends, but very few kids are interested in preparing a Spritz at home, or buying it ready-made. Not so with young people outside Italy: for them, a winery in Verona called Cantine Riondo launched a new product in 2010: iSpritz.

“We were inspired by the famous drink served in the most fashionable Italian wine bar,” explains winemaker and general manager Abele Casagrande. “iSpritz is made with our best Prosecco, and a few other natural ingredients. It has a typical orange color, modern packaging and a low alcohol content (8.5%). Currently we produce 400,000 of bottles every year, exported to 15 countries including Switzerland, Austria, Spain, Holland, Brazil, China and Japan. Very recently we started to export it to the US. We are happy with the product and its success; this way of drinking is becoming not only a trend, but a genuine icon of the Italian lifestyle.”

“We were inspired by the famous drink served in the most fashionable Italian wine bar,” explains winemaker and general manager Abele Casagrande. “iSpritz is made with our best Prosecco, and a few other natural ingredients. It has a typical orange color, modern packaging and a low alcohol content (8.5%). Currently we produce 400,000 of bottles every year, exported to 15 countries including Switzerland, Austria, Spain, Holland, Brazil, China and Japan. Very recently we started to export it to the US. We are happy with the product and its success; this way of drinking is becoming not only a trend, but a genuine icon of the Italian lifestyle.”

Here are a few important notes about ingredients to remember when creating your own perfect Spritz:

1) Orange slice: only in the Aperol version! If your Spritz has Campari in its formula, serve it with a slice of lemon.

2) Olive: well, do you really, really want it? It’s a Spritz, not a Martini! Put some olives in a small bowl on the table, instead of in the glass.

3) Ice: in the strongest versions (usually served in Padua), and during winter season, you don’t need it—trust me; in the summer, you can add just two or three small cubes

4) The glass: a short tumbler is best if your Spritz has an “important” dry white wine (not a sparkling wine) like a Verduzzo or a Incrocio Manzoni; for a stronger Spritz (for example, one mixed with Cynar), choose a tall glass

5) Last but not least, the companions! They must be the best: you and your closest friends.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/162f729-e1266674226608.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Elisabetta Tosi is a freelance wine journalist and wine blogger. She lives in Valpolicella, where the famous red wines Amarone, Ripasso, and Recioto are produced. Professionally, she serves as a web-consultant for wineries, and in her free time writes books about Italian wines. She is also a contributor to Vino Pigro.[/author_info] [/author]