Joel Peterson. Brice Jones. Richard Arrowood.

Not so long ago, these three men were among the most-recognized winegrowers in Sonoma County, and all three can still draw a crowd whenever they pour wine. It has been years, however, since Peterson was in full cry at Ravenswood, demanding “No Wimpy Wines,” and tastes have changed somewhat since Jones and Arrowood were dazzling drinkers with their vineyard-designated Chardonnay: Jones at Sonoma-Cutrer, which he owned, and Arrowood as winemaker at Chateau St. Jean.

But don’t write them off to retirement just yet. They may no longer be the thoroughbreds on the race track they once were, but neither are they ready to be put out to pasture. I caught up with all three winemakers this spring at the annual Sonoma Barrel Auction, where they were individually participating in pre-auction tastings.

I saw Peterson first at the Ravenswood stand, holding court in his cowboy hat and a stubbly shock of mustache and beard as friends and admirers stopped by. Now 70, he has been trying to slowly work himself out of a job since he sold the winery in 2001 to Constellation, who was smart enough to know that having the Godfather of Zin still associated with the brand brought them almost as much value as having the winery itself.

Like most writers, I have talked with Peterson a few times through the years and always find him full of ideas and explanations, going far beyond the standard “the wine is made in the vineyard,” although he does believe strongly in the power of single-vineyard wines. As much as I admire – and drink – his Zins, I always enjoy talking with him more.

Peterson was a medical lab chemist when he started Ravenswood in 1976 and continued to work both jobs for a couple of decades just in case the Zinfandel business got zapped. “Now, I’m going back to doing what I set out to do when I started,” he told me when the crowd thinned out, which is making small-batch wines from old vines. While fame and fortune are nice, they can have the power to accelerate original plans, especially when raising a family. That was the case when Peterson created Vintners Blend Zinfandel in 1983. It became an overnight, big-volume success, and he could no longer just be the small winemaker he set out to be, even though he still created single-vineyard Zins.

We chatted for a while about his new venture, tellingly named Once & Future, before I moved on to the next table. As he usually does, Peterson says it best himself, with this statement from the Once & Future website:

Once and Future Wine is the return to the original vision I had for Ravenswood so many years ago – a small project specializing in wines from unique older vineyards, made with a sensitivity to place and in a style that I personally love and believe in. Wines that force me to dust off the old redwood vats and get out a new punch down tool (my original is in the Smithsonian), wines that dye my hands a harvest shade of black/purple and sometimes force me to take an additional Ibuprofen in the morning. In short – wines of sweat, commitment, and love.

By contrast, I had never before met Brice Cutrer Jones, although his Sonoma-Cutrer Chardonnays were a favorite of a wine tasting group-cum-hard-partiers I once headed. “I want you to meet someone who likes to argue almost as much as you do,” a colleague at the auction said, leading me to the Emeritus winery stand where Jones was pouring wine with his daughter Mari. Part of her father’s charm and his frustration, she says, is that he is a perfectionist.

In 1973, about the same time that Peterson was learning winemaking from Joe Swan, Jones — an Air Force fighter pilot and Harvard Business School graduate — planted vines near Windsor that in time yielded some of California’s best single-vineyard Chardonnay. In 1999, he sold 80 per cent of Sonoma-Cutrer to Brown-Forman, and two years later he was fired from the winery following organizational disagreements with the new majority owner.

“I had done Chardonnay,” Jones, now 76, told me. “I wanted to make red wine.” Not only that, he decided to dry farm the grapes and grow them organically. The result was the appropriately named Emeritus Vineyards, headquartered on the Hallberg Ranch property, which he’d purchased about the time he entered into the brief partnership with Brown-Forman. Keeping his Burgundian tendencies at the new winery, Jones only grows and makes Pinot Noir. And while these wines may not have gotten the public attention that his Sonoma-Cutrer Chardonnay did, they do draw high ratings and moderately high prices.

Jones believes more strongly than I do about how far the influences of terroir can reach into a wine, so it meant for an interesting conversation over a glass of Hallberg Ranch Pinot Noir. Mari just smiled. “Let me know if you need anything,” she said when it was time to leave.

I did not catch up with Richard Arrowood until the morning of the auction. A contemporary of both Jones and Peterson, he made his first wines for the new Chateau St. Jean in 1973. It was clear from the beginning that its owners wanted to make a big splash, most notably with the decision to make a series of vineyard-designated Chardonnay wines that gave store owners both delight in having them and chagrin at the shelf space they took up.

I first met Arrowood around 1980, when I was writing a wine column for the late Washington Star. At the time, Sonoma wineries suffered from a bit of an inferiority complex, as big brother Napa Valley was getting all the attention. At an annual wine event in nation’s capital, clearly in response to this little brother stigma, Chateau St. Jean — who was always thinking bigger — upstaged everyone by arriving at Union Station in its own rail car.

Arrowood left St. Jean in 1990 to work full time at his own Arrowood Winery, which he had founded four years earlier. After selling in 2000 to Robert Mondavi, he continued as winemaker, as he did after Constellation bought Mondavi, and after Constellation sold it to Legacy in 2005. In 2010, Arrowood left his eponymous winery to devote his full time to Amapola Creek, which he and his wife Alis founded in 2001. For the second time in his career, he’d started a new winery before he left the old one.

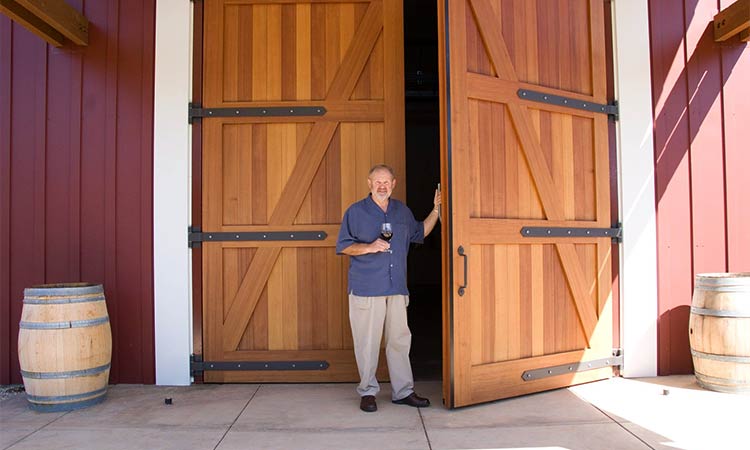

“To be truthful,” he laughed, “I wanted to have more time to go to Montana and hunt,” which the small winery permits him to do. Amapola Creek has a beautiful setting on the western slope of the Mayacamas Mountains, and I have the idea that Arrowood has more settled in than dropped out, in spite of his desire to spend time at the couple’s second home in big sky country.

Although of similar ages and accomplishments, these winemakers’ late careers are in many ways quite different. This isn’t unusual, in that many people who ‘retire’ from a larger stage have varying scenarios as to what they want to do next.

Arrowood wanted to still make wine, but also wanted to spend more time in the great outdoors where, if he saw deer, he didn’t have to worry about them eating his vines. Jones, on the other hand, wanted to have a totally different challenge in winegrowing – different grapes and different vineyard practices. As for Peterson, he decided to go back to doing what he loved doing in his 20s – before success so rudely interrupted him.