I visited the International Rose Test Garden in Portland, Oregon, this summer, obsessed with sticking my nose into every multi-layered blossom. I had just finished my Intro Sommelier course and was determined to learn how to distinguish the aroma differences among all the different flower colors. We sometimes describe a wine as smelling of “rose,” but in fact one rose might smell like orange, one like black tea, and yet another like savory herbs. How else was I expected to know “white roses” from “yellow roses” during my next exam? So I began to smell.

The task was, to say the least, stimulating to more than just my nose. The ornate landscaping and careful pruning, the countless color variations and striations, the range of simple to complex petal configurations provided a feast for all the senses. But the fragrances—more fragrances than I’d ever imagined could exist, and from just one type of flower—truly took center stage. The rose is one genus of the plant kingdom, but there are over 100 species, with additional variations and sub-species. Just as Gewürztraminer will boast a different aroma than a Cabernet Sauvignon, each rose species sniffed presented me a new and interesting olfactory experience.

Our system of similes is rather elementary. It may help to have a better—though simplified—understanding how we receive and interpret different aromas, and of what exactly they are composed.

At a basic level, the olfactory system is nearly identical across many animal species. Bees use it, dogs use it, we use it. Aroma compounds are received by olfactory receptor neurons, which send the information to the lower brain for processing. Eventually the higher-functioning brain areas make use of it, and depending on the type of aroma, certain behavioral outcomes may result: pleasure, recognition, mating instinct, avoidance, stress, disgust, and so on.

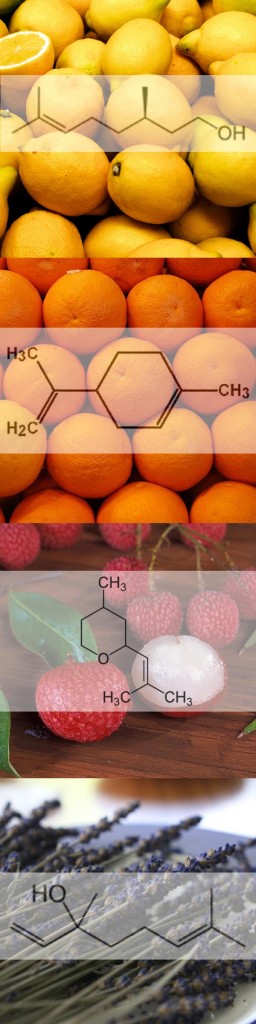

In the wide variety of roses at the garden, I noted an abundance of fresh fruit (mostly citrus and stone fruit) aromas, plus spice, and floral fragrances. Some of the primary compounds responsible for these aromas are indeed found in wines as well. Non-fruit aromas (vanilla or clove for, example) will develop if the wine is aged in wood, and these aromas will evolve and take on further complexity with aging. However, most fresh fruit and floral aromas in wines occur naturally in the grape or are related to the fermentation process. Four of these fruit/floral-related compounds are responsible for a wide variety of pleasant aromas in many plants, ranging from roses to geraniums, black tea to citrus fruit, and grapes including muscat, riesling, and gewürztraminer. They are citronellol, linalool, d-limonene, and cis-rose oxide. Citronellol, commonly found in insect repellent, bears a lemon-like fragrance, while d-limonene has aromas of lemon or orange. Linalool, also found in many citrus fruits as well as in mint, cinnamon, and lavender, can smell powerfully floral, and is commonly used in perfumes and personal hygiene products. Cis-rose oxide is likely responsible for one of the best gewürz aroma markers, lychee. Not surprisingly, the compound is found in the lychee fruit, gewürztraminer-based wines, and also in—you guessed it—roses.

Usually it is a combination of compounds that becomes interpreted as “lemon” or “lychee.” Bright fruit, warm spice, rose petals, or fragrant herbs are all generally regarded as pleasant aromas, though the odor of a bunch of decaying flowers will motivate one to discard them. Similarly, off-odors in wine—cork taint for example, with its odor of moldy basement—lead us to recoil and pour the wine down the drain. But consider Brettanomyces, yeast responsible for creating in wine a certain barnyard odor. This quality can be perceived as good or bad depending on the personal preference of the smeller.

Thus we see an additional level of complexity to the matter of aroma compounds: our sense of smell, much like our sense of taste, is entirely subjective. Interpreting the aromas of a wine—or a rose for that matter—involves the perception of individual compounds that involve a strong, learned memory of more complex aromas. It’s an imperfect association, but your brain relates the scents regardless, and thus we smell a plethora of fragrances and odors in each different glass or bloom. Environment, mood, previous experience with an aroma, and myriad other experiential factors ensure that any given smell will always be uniquely perceived.

Next time I sniff a wine and think “rose,” I’ll know to ask myself what exactly I mean. Is it spicy, citrusy, honeyed? White rose or yellow? Is it really “rose,” or does it perhaps smell like another flower altogether? My trip to my neighborhood rose garden taught me about the depth I can find in “simple” aromas, and to ponder the hundreds of compounds that make them smell “just so.”