To understand wine in Ontario, Canada, you just need to look at two maps.

First, let me answer what everybody outside Canada is asking: Why should you care? There are some world-class wines being made in Ontario that you can buy from wine shops in New York and have shipped anywhere in the U.S.

Making these wines takes courage and creativity. Some of the most impressive Chardonnays are made by a guy who buries his vines in dirt in the winter to protect them from temperatures that can reach -40.

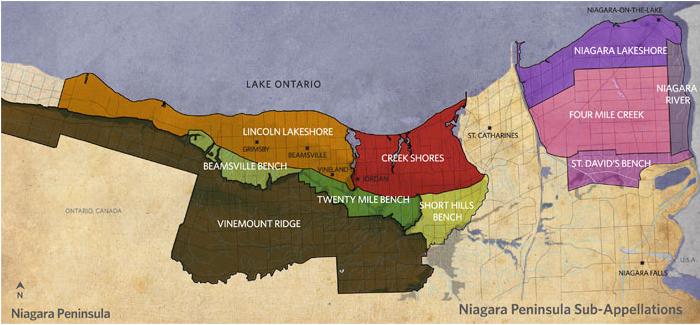

Back to the maps that tell you everything. The first is a map of Niagara Peninsula sub-appellations. Lake Ontario moderates the climate for the whole area. The closer to the lake, the warmer winter will be.

Conversely, these days, the further uphill you get from the lake, the more exciting the wine tends to be, until you get so far uphill that all the vines die in winter.

To really understand this Sisyphean appellation system, you need the second map, which shows all Canadian wine regions.

Canada is humongous: the second largest country in the world, after Russia. And Canada drinks 10% more wine per capita than the United States. It’s the world’s 14th largest wine consumer, ahead of wine producers like South Africa, Chile, Greece, Hungary and Austria. In short: big country, pretty big market.

When looking at the second map, of Canada’s grapegrowing regions, it’s worth knowing that we’re using the most optimistic version we could find. Places with lots of vineyards are in purple. The green spots are dreamers.

The biggest sliver of purple is in British Columbia. There’s nothing in the middle of the country. On the east coast, hugging the U.S. border, are the wine regions of Ontario. Most of the green spots you see north of there are where hybrids are planted. For vinifera, Ontario and British Columbia are it.

Busloads of tourists come to Ontario’s wine country every day, but not for the wine. Niagara Falls is nearby, and the U.S. is just over the Niagara River.

Take the tourist helicopter over the falls, and if you’re a wine lover, the difference in vineyard plantings across the border is more impressive than the cascading water. On the U.S. side, there aren’t any that I could see. In contrast, from the air, the Canadian side looks like Burgundy or Napa Valley or any other wine-is-king region, with vineyards on all plantable space. I bet you didn’t think anywhere in Canada looks like that.

People in Canada tell you that the terroir on the Canadian side of the border is better than on the U.S. side. That may be true, but in vineyard plantings, it’s as if you took a helicopter from Burgundy to England. I believe it’s because U.S. farmers have always had better places to put vineyards than beside the Niagara River, while Canadians haven’t.

The history of Ontario wine stems from that map. Canada is a huge wine market with very little usable terroir. The Ontario wine market is not only Canadians, but tourists visiting Niagara Falls. The safest area in the entire eastern part of the country to get a reliable crop of grapes is in the warm, fertile soils by Lake Ontario. People like red wines. Hence, an Ontario wine industry sprung up with the only imperative that the wines be adequate, and with red wines being more the focus than whites.

That’s the story of the second map, which brings us back to the first one, and the reason I’m writing this at all: the great wines Ontario is making now.

Two key offshoots of having an existing, if lackadaisical, wine industry were, 1) people wanting to grow grapes in Ontario had a place to sell them, and 2) professional winemakers working in the bigger wineries couldn’t help noticing that some grapes were better than others.

You can go 20 years without hearing the word “escarpment” in most of the English-speaking world, but it comes up every 3 minutes in talking with an Ontario winemaker. The Niagara Escarpment is a long cliff; Niagara Falls is part of it. There’s a lot of limestone, and it’s old enough that in many places it’s more of a hill than a cliff. Limestone hills: yep, that’s good vineyard land. It’s also risky, because Niagara is a region where winter frost kills not just crops but the vines themselves.

Here are some great wineries on that escarpment, and one that’s even more extreme.

Hidden Bench: Harald Thiel was an international merchant of audiovisual equipment when he had his epiphany. He was skiing in Europe with a friend who had a heart attack. Thiel gave him CPR for 17 minutes. “I said to myself, if he pulls through this, I’m going to start a winery,” Thiel said. Hidden Bench is certified organic and uses only estate fruit. A lot of people make Pinot Noir in Ontario now, but his were the best I tasted, with great freshness and minerality. Hidden Bench recently won “best white wine” at the Canadian Wine Awards for its “Nuit Blanche” Sauvignon Blanc-Sémillon blend, but I’m more impressed with its steely Rieslings and complex, savory Chardonnays.

Tawse Winery: A spare-no-expense project funded by a Burgundy fan, Tawse has strict Burgundy-like protocol for its Chardonnays, with all native yeast and all whole cluster fermentation. All Chards are barrel aged on the lees for a year with no stirring and no racking, because “we want the protection (from oxidation) but we don’t want to build flavor that way,” says assistant winemaker René van Ede. The result is a thrilling portfolio of intensely flavored single-vineyard Chardonnays. Tawse also buys some Cabernet Franc from closer to the lake and makes the best Meritage I tasted in Ontario.

Bachelder: Thomas Bachelder is a frantic genius who thinks faster than he talks and talks faster than most listeners can process. After a long winemaking career, much of it in Oregon, he now makes wine under his own label in Burgundy and Oregon and Ontario as well. “I would characterize Niagara as having the minerality of Burgundy, but with a more floral thing,” he says. His Chardonnays are world-class from all three regions.

Cave Spring: The first Ontario wine I fell in love with was a Cave Spring Riesling I tasted at Riesling Rendezvous, and its total acidity was so high that the audience of international winemakers laughed. The Pennachetti family are among the pioneers on the escarpment, daring to plant uphill and planting the region’s first Riesling because, though they were from Italy, that’s what patriach John Pennachetti loved. Cave Spring Riesling is terrific, with strong minerality and floral notes and freshness that’s worth of a good hearty food-loving laugh.

Norman Hardie: Hardie was among the first to plant anything in Prince Edward County, which is on the other side of Lake Ontario from the Niagara Peninsula. He buries his vines in dirt in the winter to protect them, which sounds insane until you consider two things: 1) The resulting wines are amazing, rich and flavorful yet fresh, with alcohol levels around 12%, and 2) Hardie bought 50 acres of land and planted it with Chardonnay for $1.2 million total. “I drove in and saw the limestone and said, ‘Yeah!’ he says. “I built the building myself to save myself that $400,000.” Hardie got into wine because he was a sommelier at Four Seasons hotels. “I worked seven days a week and I didn’t spend anything,” he says. “They bought my clothes. They bought my food.” He saved his money and now he’s a winey owner, albeit one who has to get his hands dirtier than most. “It’s a little more challenging farming my vineyard because everything’s close to the ground,” he says. “You’ve got to have good knees.”