A little over two years ago, I wrote a piece for Palate Press entitled “Screw cap vs. Cork: Which is Greener?” in which I compared what we know about the environmental impact of natural cork versus aluminum screw caps. Cork came out clearly on top, save for the strong and sensible argument that cork taint causes a whole lot of unaccounted-for waste. The responses to that piece – 101 comments as I write this – stand as a fairly remarkable testimony to how much the wine community cares both about the environment and about closures.

At the time, I didn’t discuss Nomacorc – the largest manufacturer of synthetic bottle stoppers and a major alternative to natural cork and screw caps – because data on the environmental impact of Nomacorc’s production process wasn’t available. That’s changed. The public summary of Nomacorc’s recently completed environmental life cycle assessment has just been released, so it’s time to give the “which is greener” closure question an update.

At the time, I didn’t discuss Nomacorc – the largest manufacturer of synthetic bottle stoppers and a major alternative to natural cork and screw caps – because data on the environmental impact of Nomacorc’s production process wasn’t available. That’s changed. The public summary of Nomacorc’s recently completed environmental life cycle assessment has just been released, so it’s time to give the “which is greener” closure question an update.

As I noted in the original article, these kinds of analyses are unquestionably best when generated by people who have no stake in the game. Unfortunately, the only data publicly available has been funded by either Corticeira Amorim, the internationally leading cork manufacturer, or by Nomacorc. Amorim’s life cycle analysis, released in 2008, compares natural cork, screw caps, and molded plastic “corks” (the molded plastic closure came out so much worse than either cork or screw cap, and has fallen so far out of favor, that I’ve ignored it from here on out). Nomacorc’s analysis, released this fall, only covers Nomacorc. The two studies were conducted by different agencies using potentially different methods – Nomacorc isn’t releasing enough information about their methods to know how they might compare with the Amorim study – so their results may have been calculated in different ways. So consider this a picture painted with broad strokes, and don’t take the specific numbers too seriously.

A life cycle analysis (LCA) measures the environmental impact of a product from the origin of its raw materials to its disposal or recycling – “cradle to grave.” Nomacorc’s LCA covers only “cradle to gate” – from raw materials to shipping finished stoppers to bottlers and distributers – excluding bottling itself and shipping bottles containing Nomacorcs to consumers and looking at disposal in a separate analysis. They looked at their Belgium and North Carolina plants separately; I’ve used the North Carolina numbers here, but the differences are relatively small. Data for natural cork and screw caps are based on producing the cork in Portugal, the screw cap in France, and using and disposing of both in the UK. Neither Amorim’s nor Nomacorc’s analyses accounted for either the capsule (usually tin or some kind of plastic) used to cover natural and plastic corks or the process of coloring or printing on any of the closures.

The most important thing to realize about natural cork production is that harvesting cork doesn’t kill the cork tree (a species of oak called Quercus suber L.); in fact, cork forests are a major biodiversity haven and the trees are protected by law. Screw caps are made from aluminum plus a plastic lining. Producing aluminum from bauxite – a mixture of aluminum hydroxide and impurities obtained by surface mining – leaves behind toxic sludge called red mud which, when not properly contained, can kill people.

Nomacorcs are made of plastic, even though you’ll never see that word anywhere in their marketing materials. The company is extremely secretive about their special recipe and the life cycle information they’ve released doesn’t describe what their raw materials are or where they come from, but the company says that the closures can be recycled with #4 low density polyethylene, or LDPE. LDPE is the same plastic from which plastic shopping bags are made, the stuff of oceanic plastic islands, poisoned fish, and crowded landfills. If you consistently eschew plastic shopping bags for environmental reasons, you might need to think about eschewing the Nomacorc, too.

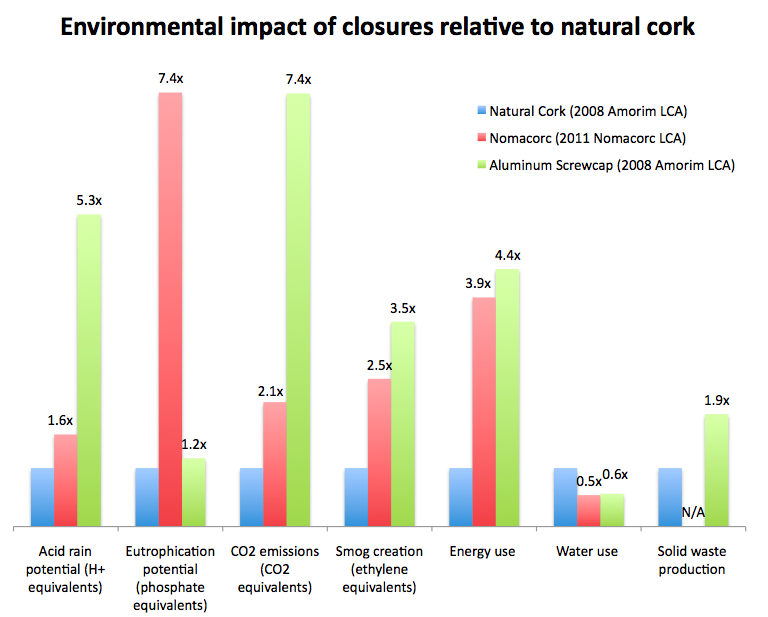

The Amorim-sponsored LCA found that, compared with aluminum screw caps and plastic corks, natural cork production used the least non-renewable energy, generated the smallest amount of greenhouse gases, contributed the least to atmospheric acidification and water eutrophication (eutrophication = adding extra nutrients to water, causing unusually high algae growth and disrupting water ecosystems), and produced the least solid waste. Aluminum screw caps won out in one respect: their manufacture uses the least water.

When I toured Nomacorc’s North Carolina plant last year, I was astonished by how much water seemed to be involved. After the various types of plastics (that secret recipe) are melted, combined, and extruded, what amounts to a giant Nomacorc log – the uncut closure material – is passed through a long water bath as it cools and solidifies (Wine Folly has a great video of the tour here). I almost expected to see fish swimming around in there, though I’m sure that their very active safety officers would have something to say about that. The LCAs reminded me, though, that the Nomacorc process isn’t unusual. Most manufacturing requires a lot of water and natural cork in particular requires an inordinate lot of washing. Producing a Nomacorc actually uses much less water than producing a natural cork, and about the same amount as producing an aluminum screw cap. Nomacorc wins on water use.

Nomacorc loses on a lot of other counts, though. Their data say that Nomacorc production does much more to turn rivers green and murky (eutrophication potential) than either natural cork or screw cap. It takes nearly as much energy to make a Nomacorc as a screw cap: about four times what a natural cork requires. While Nomacorc’s potential smog production is lower than the screw cap, it’s still more than twice as high as the natural cork. It is the same for carbon emissions- even if we don’t count the offset that the natural cork folks like to give themselves for the carbon-absorbing potential of the cork forests; Nomacorc comes in about twice as high as natural cork, but significantly less than screw caps.

That carbon offset for the cork forests has riled a lot of folks who say that natural cork companies are unreasonable in using it to their credit. The cork forests would continue to exist without wine cork companies, they say, and so the contribution of the forests has nothing to do with the companies’ greenness. I think that there’s a strong argument to be made for thinking that economic pressures have a lot to do with conservation – without the influential support of the wealthy cork companies, the forests might not be as well protected – but that’s speculation better left to an economist than to me. The more important realization is that, even without counting the carbon offset credited to the forest, natural cork manufacture still puts out only half the carbon of Nomacorc manufacture, and about seven times less than the screw cap. Every company, of course, works the numbers to their best advantage. Nomacorc claims that “because 90% of the environmental footprint of Nomacorc closures is due to raw materials used, every closure that is recycled has a corresponding 90% reduction in environmental impact.” But the recycling process uses energy and water, too, and so Nomacorc’s assertion probably isn’t quite true.

The most important realization, in fact, might be that closures don’t have much to do with the overall environmental friendliness of your wine. Producing what’s inside the bottle uses far more water than making the closure ever could, both in terms of watering the vines and the near-constant washing of winery equipment (it’s been said that being a winemaker is like being a janitor, only a lot colder and wetter). Glass bottles are energy-intensive to make and heavy and bulky to ship. In addition to improvements in the vineyard and the winery, much of the innovation toward making our favorite drink greener has been aimed at the glass bottle – refillable bottles, variations on the bag-in-box and the wine pouch, Tetrapaks, cans, the new recycled paper “bottle” – and rightfully so. (And don’t even get us started on the Styrofoam shipping inserts used to direct ship wine. Ed.)

Brands are always trying to tell a story. Nomacorc’s story, here, is improvement. They present numbers from their production process as it was in 2008 and as it had changed by 2011 and, in every case, the 2011 numbers are better. It’s fair to say that Nomacorc cares about its environmental impact and is working to improve it. Nomacorc has also recently released a line of closures made from polymers derived from sugar cane, a renewable resource. The natural cork folks still have their beautiful photographs of the iconic cork forests to set up next to images of bauxite mines and oceanic plastic islands. I wouldn’t blame you for feeling happier about natural cork because those pictures give you the heebie-jeebies. (I do.) But when it comes to making an environmentally friendly decision about what to drink tonight, it’s fair to say that you can focus your concerns on something other than what’s covering the top of the bottle.

*Amorim has moved the web location of the life cycle analysis I cited in the 2011 piece, so the hyperlink citation from that article no longer points to an active location. You can now find that report here.