On a recent trip to the Finger Lakes, my husband and I were amused to encounter a wine list that was not exclusive to local wines. We were less amused when it happened again. As a pattern slowly began to emerge, we could not help remembering vacations to Sonoma County and Austria, where local wines dominated the menus and wine shops. Our conclusion: the lack of local pride within our own state was pitiful. In New York City, where we live, we have basically resigned ourselves to the fact that wine shops and restaurants cannot limit their selections, although it has always seemed strange that local wines do not have a stronger presence here. In Finger Lakes wine country, however, one might expect otherwise. The problem seems widespread, begging the question: What is it going to take for New York wines to get the presence they deserve across New York State? Why are they so difficult to find outside tasting rooms?

These questions have been asked before, and responses typically fall along these lines: 1) the Finger Lakes produces lesser quality wines, 2) smaller-sized wineries cannot manage production at large enough scale to infiltrate wine shops and restaurants around the state, 3) these wines struggle to get picked up by the big distributors, and, when they do, they get lost among those distributors’ heavyweight clients, and, 4) New York wines simply cost too much for their value.

These excuses can be easily dismissed. It’s no secret that Finger Lakes wines haven’t always been great. In the early days, quality suffered as wineries tended to focus on syrupy sweet wines from native varieties (the prevailing belief being that those were the only wines the region could grow). “It can’t be a quality issue” anymore, says Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards on Seneca Lake. Finger Lakes wines regularly take Gold and Best in Show awards on the international stage, and earn 90+ point reviews. In addition, frequent accolades in both trade and mainstream publications continue to draw attention to these wines and the region, as do the nods from winemakers and sommeliers around the country.

Distribution has always been an issue for smaller producers, even in California. Consider that New York is the second largest wine producer by volume in the United States, thanks to five major wine regions—Lake Erie, the Niagara Escarpment, Hudson Valley, Long Island, and the Finger Lakes. Yet customers are more likely to find Washington or Oregon wines in New York City, even though within New York State, it is easy to order direct from winery or through a distributor. “Most of us have distributors,” remarks Osborn, “so delivery and ease of ordering is taken care of.”

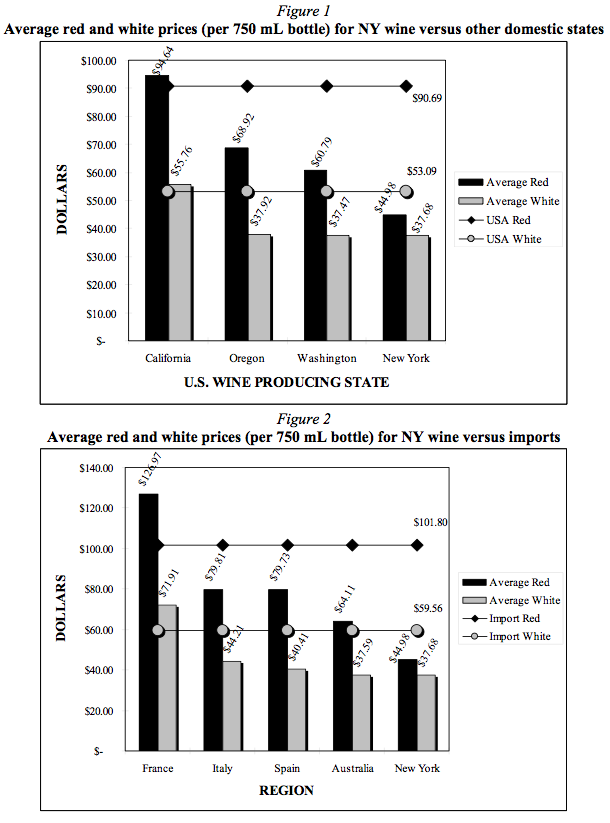

New York wines seem to be associated with high cost, as well. New York City wine shop owner Marco Pasanella, in his book Uncorked: My Journey through the Crazy World of Wine, lamented that he cannot justify selling local wine at the $20 price point. In New York City restaurants, the average price of local wines–$44.98 for red and $37.68 for white, according to a 2008 working paper in the Journal of Wine Economics—does seem high, until a closer look reveals New York wines to be the least expensive compared to their domestic and international counterparts (with the exception that white wines are nine and twenty-one cents more expensive, respectively, than Australian and Washington State imports).

Not only are they on average less expensive, Osborn adds, “take the scores in major wine magazines as an indicator of quality and take the same scores from other regions, you will find most Finger Lake wines are one to five dollars less expensive for the same quality.”

Having debunked the myths, it would seem that the Finger Lakes should be a major contender in the United States wine industry, if not around the world. Yet, Finger Lakes wines struggle to gain traction, even in their own state. The problem boils down to consumer perception. In an anonymous online survey conducted by this author (n=15), 80% of respondents said they were familiar with New York State wines, and had even drunk them in the past, but only 60% of those respondents agreed that New York produces quality wine, compared to 80% who agreed that California does. The vast majority (80%) were self-described as “intermediate” level of wine knowledge, too.

“Certain prejudices still prevail,” agrees Osborn. “Those not following the serious wine story up here tend to assume we are producing the same types of sweet jug wines that dominated the scene 40-plus years ago.” Pascaline Lepeltier, Wine & Beverage Director at New York City restaurant Rouge Tomate, adds, “there is still work to do in terms of education regarding the high quality of production of certain winemakers.” The biggest challenge for Upstate Wine Co. owner Kevin Faehndrich in the early days of his distribution business was educating customers by exposing them to “new, unique, high quality wines” from the Finger Lakes.

Even “local” themed restaurants in New York City offer international and west coast wines, but perhaps this is critical: while twelve (80%) of survey respondents agreed to, “I place importance on purchasing ‘local’ services and goods,” only one respondent (6.7%) agreed to, “I am more likely to choose wines from NY State over wines from other regions.”Rouge Tomate’s focus on quality ingredients that are true to place, with respect for the biological and social environment, means great opportunity for New York State wines. Yet although Lepeltier’s wine list comprises of 10% local wines, slightly less than 10% of wine sales come from those local wines, she notes—and not for lack of effort. “We really recommend local wines, especially to international clientele or non-New Yorker guests that visit Rouge Tomate,” she explains. “A lot of New Yorkers know about them without realizing the level of quality.” She surmises that the image of both the Finger Lakes as a “concord grape” place and of Long Island as a beach destination still overshadow the regions’ wines.

Blue Hill Farm’s trademark “know thy farmer” philosophy means a focus and transparency on local food sources; yet, only “a small amount” of sommelier Claire Paparazzo’s wine list is devoted to local wines. “We do believe in the local sustainable movement, but a lot of my list is devoted to farmers from all over the world who are working with the land in the most respectful way. I choose to honor that,” she says. Like Rouge Tomate, local wines account for about 10% of wine sales, and like Lepeltier, Paparazzo does her best to recommend local wines: “I really see the interest in local wines from people visiting from other countries,” she notes. “I don’t find the same interest in native New Yorkers,” she says, adding, “perception precedes quality” with customers. Currently, Sancerre and Oregon Pinot Noir are popular choices, ironic from customers who’ve chosen a restaurant specifically for its connection to locally sourced ingredients.

Even within the Finger Lakes, restaurateurs are not willing to risk offering a local-only wine list. “Every day we see advertisements from restaurants saying they buy only local ingredients,” notes Scott Osborn, “but the first thing we notice is that they have a California or imported wine list and no local wines, or perhaps a token one just for show. These folks have a double standard.”

“I can name on maybe one hand, those [restaurants] who are Finger Lakes only,” adds Kelly Towers, Lodging & Dining Manager and Sommelier at Belhurst resort’s award-winning Edgar’s Restaurant. Although Belhurst Estate Winery leads in sales by the glass, the restaurant’s 17-page wine list consists of 40% local wines which account for 30% of overall sales. “I feel it is important to offer wines from outside the Finger Lakes in order to offer something that will please all palates,” she remarks. “Some guests have this notion that Finger Lakes wineries do not do a good job at producing red wines. As much as I disagree…instead of getting into an argument with a guest, I make sure that I have something on hand to offer them.” She points out that perceptions of Finger Lakes as sweet wine producers still prevail, and that smaller productions hurt the region in terms of attracting visitors. On the positive, she notes that “we have guests coming mainly from all over this nation, and occasionally from international countries, coming to taste our highly rated wines.”

Raymond Szymanoski, Director of Food & Beverage at the Ramada Geneva Lakefront on Lake Seneca argues that, “it would be hard to do a wine list with just the local offerings. With so many people coming through from different areas, not everyone would be sold on [my] offering just local wines. Some customers are just looking for names they know and like certain varietals that are not produced locally.” His wine list boasts 40-45% Finger Lakes wines, which account for 55%-60% of overall wine sales. “There is a great market for these wines and customers appreciate the offerings of local wines,” he concedes, noting that, while Finger Lakes whites are popular, “the reds are difficult.” Importing from other regions means meeting customer requests for certain varietals.

Even as customer perceptions continue to hold back the success of local wines, there seems to be hope on the horizon. Faehndrich points to expert influence. “Customers of [our client] restaurants are willing to try a new wine varietal, style, or region because it has an implied stamp of approval of the sommelier and the restaurant as a whole.” In retail shops, “customers buying habits are influenced by the stores’ recommendations,” he adds. The sommeliers interviewed for this article indeed say they recommend local wines. Towers steers guests towards Finger Lakes wines, and notes, “much of the time, a guest will order local when guided that way.”

Perhaps misperceptions of Finger Lakes wines are fading. In addition to the readiness of international visitors to try New York wines, “I see a shift in attitude, mostly with Millennials,” offers Osborn. “The younger restaurant owner/buyer/sommelier or the owner/buyer of a specialty wine shop doesn’t remember the ‘good old days of sweet jug wines.’” Without the prejudices of their older counterparts, younger customers “are looking at the Finger Lakes as a great American wine region,” he adds. Towers sees a shift, as well. “We are on the cusp of something big! Certain wineries have a cult following that buys them out of wine vintage after vintage. This speaks leaps and bounds to where we were 14 years ago when I started tasting Finger Lakes wines.” Faehndrich even sees it in New York City. “Buyers can afford to be extremely discerning,” he points out. “Yet, I have seen a significant increase in market presence of Finger Lakes wine in the great NYC market over the last couple of years, which suggests that Finger Lakes wines are gaining traction.

Perhaps the problem in New York City is that local wines get lost in the sheer volume of all that’s available. “The absence of strong New York wines sales in New York City is not necessarily due to a predominantly negative image of the product quality, nor to high prices,” concludes the aforementioned 2008 study by Preszler and Schmit. “Instead, low sales in NYC can likely be attributed to the lack of any specific image at all.” The scientists’ recommendation: “A coalescence of marketing goals and principles among New York winery stakeholders could make a difference in this regard.” The “Uncork New York!” ad campaigns are a great start.

When asked what it would take to increase presence of local wines, Osborn recommends customers tell the manager or owner, because wait staff are “too busy serving you to remember at the end of the day to tell the owner.” Paparazzo suggests that, “time is going to the factor in getting people to open their minds and mouths to accept New York wines to be the flavor experience that they crave, but I feel people will accept it when they taste something that is good but don’t know where it is coming from.” This sounds a lot like the now famous 1976 Judgment of Paris, the blind tasting that pitted the best of French against California wines. California wines had been struggling with negative perceptions similar to what New York faces today, and the win for California brought legitimacy to the wines and was the first step in earning the global reputation they have today. Time, patience, and consumer education is critical; yet, this author can’t help but feel another Judgment of Paris is in order.

Editor’s note: In the original version of this article, the name of Claire Paparazzo was misspelled. Palate Press regrets this error. Trent Preszler, the corresponding author on the AAWE working paper, is currently the CEO of Bedell Cellars in Cutchogue, NY, in the North Fork of Long Island AVA. The paper was submitted as part of a master’s degree thesis at Cornell University.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Kristina-Anderson-Author-Photo.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Kristina Anderson is an Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, and together with her husband, the publisher of www.localvinacular.com, a wine blog focused on wine education and enjoyment. They live in Brooklyn, NY. [/author_info] [/author]