A Brit writing on Napa Cabernets, for an American wine magazine – isn’t that a bit bloody minded? A tad “coals to Newcastle”, if you will? Stay with me, it might get interesting.

California’s Napa Valley has nothing left to prove – the 1976 and 2006 Judgments of Paris are merely the most visible evidence that this wine region is one of the world’s finest. But sometimes greatness is hard to approach. Napa’s French sparring partner, Bordeaux, is a case in point – if you’re heard of the châteaux, you can’t afford the wine, you can’t visit without an appointment and it won’t be a rustic vigneron that greets you – rather an investment banker or a coiffed, suited and booted media executive.

Napa has regrettably moved in a similar direction – the best wines are increasingly unaffordable for mere mortals, and top properties have slammed their gates shut to “ordinary” wine lovers. When I was last in the area, I chose to visit Sonoma instead – “Less Disneyland, more down to earth”, was a local contact’s advice.

Lindsay Hoopes, from self-styled “ultra-premium boutique” Hoopes winery sympathized with my view, when we met at Prowein (Europe’s largest wine trade fair): “We know Napa has become a bit inaccessible, there’s a group of smaller producers like us who are trying to reverse that”. Even better, she poured me a selection of Cabernet Sauvignons from five different Napa producers, including her own.

If there was a common theme, it was balance. Napa valley is hot – significantly moreso than neighboring Sonoma, hence the dominance of Cabernet, which needs plenty of sun to ripen properly. But that heat is offset by a diurnal difference of some 40°F, which helps to give these wines their finesse and freshness.

I’ve come clean about occasional high-alcohol hangups before and couldn’t help noticing that most of the bottles claimed 14.9% alcohol – do producers deliberately try to keep that figure under the 15% watershed (up to 1% tolerance is allowed on the label in wines over 14%), to avoid prejudicing opinions about the wines being too big? Lindsay ponders for a second before replying cautiously “No, I think Europeans are far more hung up about the alcohol than Americans”. Whether that’s true, I could not accuse any of these Cabernets of being overripe, or unpleasantly “hot”.

Five Napa Cabernets

Staglin Family Vineyard’s 2008 Cabernet Sauvignon (Rutherford AVA) was the biggest and broadest, with noticeably soft tannins, a lot of oak and very forward. Neither to my taste, nor my budget – a wallet-busting $150+ a bottle.

Grgich Hills Cabernet Sauvignon 2010 (Yountville, Rutherford and Calistoga AVAs) was noticeably more structured, with minty freshness and dusty plum fruit. Not the most complex of the bunch, but I could imagine drinking this very enjoyably. Good value at $50.

Beckstoffer Missouri Hopper Vineyard Worlds End 2009 (Oakville AVA) also had a dusty quality to the fruit, attractive cigarbox and mint aromas, and a rather compact palate. $85+

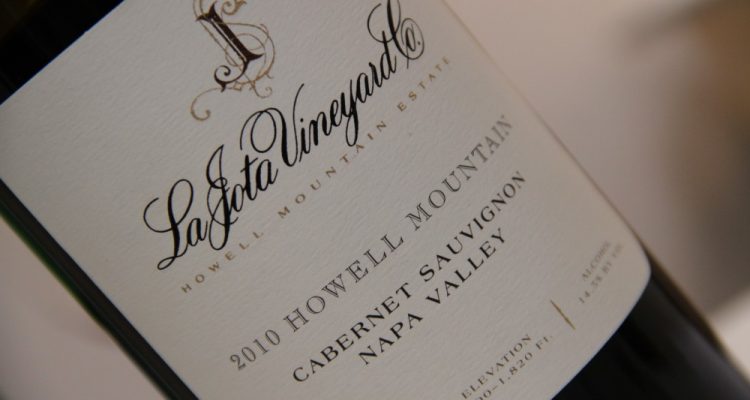

* La Jota vineyards Cabernet Sauvignon 2010 (Howell Mountain AVA) has historical pedigree, Swiss founder Fredrik Hess created it in 1898. The vineyards are at altitude (1,700 – 1,800ft), and this is all about fresh blackcurrant and bayleaf, with good grip on the finish. A relative steal at $50ish.

* Hoopes Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon 2010 (Oakville AVA) really impressed with its sinewy, fine-grained tannins, lithe and leafy elegance and effortless handling of 14.9% alcohol. Around $65.

There’s a good story here – Lindsay’s father planted his vines on grafts in 1983, something that was rather pooh-poohed at the time. The Hoopes family are laughing now – following the surprise phylloxera outbreak in the 1990s, they now have some of the oldest vineyards in the region. I’m sure this is a factor in the excellent quality of the wine, even if as Lindsay says “It was more dumb luck than anything else – my dad just loved French wine, so he did everything the French way.”

Regional variation

My takeaway from this mini-tasting was twofold – Napa’s 16 AVA sub-regions cover a huge variety of terroirs – volcanic, gravel or clay soils, steep hillsides, mountains and valley floors. My preferences gravitated towards the cooler zones or more gravelly soils (Howell Mountain and Oakville), although vintage variation and the hand of the winemaker play a role. It was no surprise that the leaner more elegant wines wooed me – the broader, bolder styles have their following, but don’t speak to my admittedly European palate.

Hearteningly, most of the producers mentioned in this article sell their wines at reasonable prices, and my favourites happened to be amongst the most affordable. Accessibility is clearly an issue – only two of the five (Grgich and Staglin) encourage visiting, whilst Beckstoffer expressly denies it. The gates might be shut, but Napa can still appeal to wine drinkers, not just stockbrokers or investors.