Human winemaking has irrevocably changed the shape of yeast populations worldwide. If we could go back in time, would we want to make the same choices?

It’s probably fair to say that humans invented wine. Humans surely didn’t invent fermented grape juice, but we probably invented its deliberate cultivation as a delightful beverage. But humans didn’t invent it alone. Much of the process – the grunt work of actually converting sugar into ethanol, plus the selection of additional flavor molecules created along the way – rested in the hands of our microscopic collaborators: yeast and bacteria, most crucially the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. By preferring some flavors over others, humans chose the particular species and strains (breeds) with which we wanted to collaborate.

This coevolution – of wine, yeast, culture, and humanity – seems to have all taken place in a fairly limited geographic region, where grapes grew and ripened in a season warm enough to let yeast feel comfortable doing their best work. Wine grapes and wine yeast were both domesticated in Mesopotamia, at about the same time, well before 5,000 B.C.E. when the farthest-back archaeological evidence we have says that a wine industry was already flourishing. The yeast probably came via one route or other from species originally associated with European oak trees, so their genetic ancestry suggests, though precisely how they ended up in the fermenting vats of the Mesopotamians is something scientists have yet to work out.

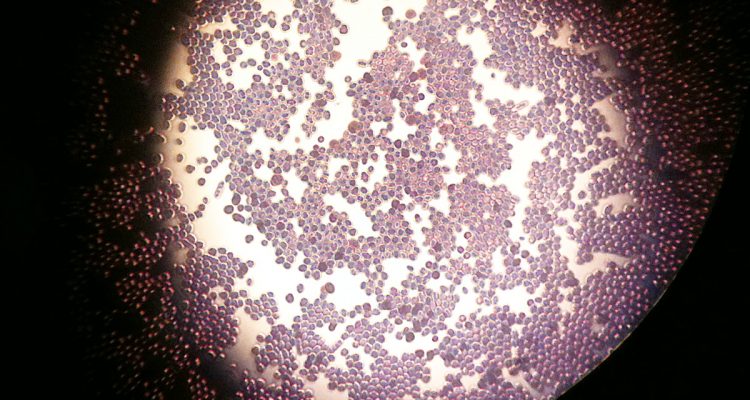

As humans traveled, wine traveled and yeasts traveled. By this point, Saccharomyces cerevisiae was, like humanity, already living in other territories; also like humans, those other indigenous yeast populations were a bit different from one another in culture and appearance. Microbial geneticists who collect samples of yeasts from around the world have found, for example, that the yeast strains that make their home around oak trees in North America are distinct from the strains that live in New Zealand soils, or in oak forests in France or Japan.

Genetically, Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from the same region tend to resemble each other. The DNA of yeasts from central Europe is more generally similar than the DNA of yeasts native to South America, which form a different cluster. But once humans began taking special care of the strains they liked best, they cultivated new genetic groupings. Today, as a result, yeasts used for winemaking tend to be more like each other than yeasts for bread baking, even when the winemaking and bread baking are happening in the same town. Human cultivation hasn’t just changed the yeasts sold in little foil packets at the grocery store or from winemaking companies. We’ve actually changed the shape of yeast genetics worldwide.

So the yeasts that volunteer to work for winemakers who like spontaneous fermentations? They’re not just any random schleps off the microbial street. They’re specialists, uniquely outfitted to work with women and men in the noble art of vinification. Most possess specific genetic traits that make it easier for them to withstand the challenging environment presented by a vat of fermenting grape juice: harsh acidity, perilously high sugar concentrations early in the process, uncomfortable amounts of ethanol later on, and the sulfur dioxide usually added to keep out spoilage microbes. They are, you could say, the Sherpas among Saccharomyces cerevisiae. And nearly all are descended from – and more or less related to – those yeasts our ancestral oenophiles brought out of Mesopotamia. They’re Sherpas who are all cousins of each other. The same sort of thing – domestication event, then dispersal – also seems to have happened for the different and unique sets of yeasts that ferment beer, sake, and palm wine.

“Wine yeasts,” by the way, mean both yeasts found in vineyards and yeasts found in wineries and fermenting wine. So much crossover happens between the two groups that it’s impossible to tell whether a yeast strain came from inside or outside the winery by looking at its genetic makeup. That’s hardly surprising. The inevitable army of insects drawn to fruit, fermenting or still on the plant, will airmail anything found in one location to the other if the two spots are within flying distance. According to Dr. Linda Bisson, wine microbiologist at UC Davis, whether yeasts originate in the winery or the vineyard is therefore “moot.”

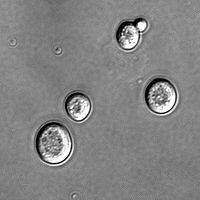

Populations of yeast associated with human industry are mostly alike in this respect. Bakers and brewers of various alcoholic beverages have all created communities – globally near-homogenous communities – of the yeast they like to work with best. But here’s the funny thing. According to new research from a group mostly headquartered in Seattle, the yeasts responsible for fermenting coffee and chocolate don’t work the same way. Both raw coffee beans and cacao pods need to be fermented very early on in their transformation into something palatable for human consumption. Good old Saccharomyces cerevisiae steps in for both jobs, but not the same Saccharomyces cerevisiae that takes on winemaking; again, the strains in each group are genetically different. But the coffee and cacao strains aren’t very specialized. They’re each much looser groupings, much more like whatever yeasts are hanging around in their general area, much less closely related to the others in their specialized work group. And, not incidentally, coffee and cacao growers don’t inoculate their ferments. Unlike most winemakers, who deliberately add yeast to each batch of grape juice – these days, usually purchased from a commercial supplier – coffee and cacao growers still let their crops ferment courtesy of whatever microbes decide to drop by.

This story has two interesting conclusions. The first is that winemaking is working itself into a microbiologically narrow corner. The second is that specialty coffee and chocolate producers can, at least in theory, try building closer relationships with their microscopic partners as a route to develop new flavors or better product consistency.

Of course we want to cultivate wine yeasts that produce desirable flavors. No one wants to work with someone who doesn’t hold up their end of the job, or who you just plain don’t like, or who turns out a product you can’t sell because it smells like dirty socks (Brettanomyces, I’m looking at you). But that means that we keep making the pool of our very tiny winemaking business partners smaller and smaller, and more and more specific, and more homogeneous. That sort of specialization is concerning for the obvious reasons: weaknesses and susceptibility to disease tend to affect the whole population. And there’s the commercial absurdity side of the problem: another yeast genetics paper out this year attests that of the many wine yeasts on the market, some sold by competing companies are identical. In theory, this problem should be easy to solve. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is remarkably accepting of new genetic material, so much so that cells sometimes take up genetic material from other species of yeast without human intervention. And there are plenty of other yeast communities to pilfer for new genetic material, and plenty of companies exploring new angles on the commercial wine yeast business. But somehow, at least according to this slew of recent wine yeast genetics studies, most winemaking is still working with a fraction of all of these possibilities.

Thinking in the other direction, could we end up with different or better flavors in our coffee and our chocolate by trying to identify and make friends with the yeast community’s A-listers in those specialty areas? Probably. Whether or not that’s practical is another question, what with coffee and cacao fermentation generally happening out in the fields of often deeply impoverished countries. But the most interesting question might be not whether we can, but whether we want tighter control over microbial coffee and cacao work. Here are two places where we can say that “wild fermentations” still unquestionably and uncontroversially exist, where the native yeast populations of any given region haven’t been irreversibly altered by the equivalent of yeast eugenics. Once we begin exercising that kind of control, we can’t go back.