This fall, instead of just talking about the Champagne Harvest, I decided to join the army of pickers who, every year, descend upon the region. In order to immerse myself in les vendanges (the harvest) I contacted Champagne Jacquesson, a small Champagne House that farms about 19 hectares of vineyard around Dizy, and asked if I could join their picking team. In Champagne, by law, the fruit has to be hand picked. People come from all over France—and in some cases from other countries—to pick. At Jacquesson, the bulk of the people are local (from the Marne area) and most of them have several harvests under their belts.

Though a lot has changed in recent decades, the Champagne harvest is still intrinsically folkloric and vibrant. The mood is jolly and most people are happy to be part of another harvest, and to catch up with old friends. And most Houses look after their harvest staff, so a day in the fields or at the press comes with several meals. At 9 AM, a coffee break and breakfast (croissant or sandwich) is delivered to the pickers, at midday a four-course lunch is served, and at the end of the day everybody has a few glasses of bubbly before going home. Very few places today house their pickers, as was done in the past. But winery staff—if they are not local—are generally given a bed, and all winery staff will generally also enjoy an evening meal (and more Champagne) together.

Harvest lasts about ten days and, like all things in Champagne, it is strictly regulated. The rules are determined every year by the CIVC (Comité Interprofessionel du Vin de Champagne) which regulates:

1. the yield per hectare for the 2012 production

2. the extra yield allowed for reserve wines

3. the average alcohol percentage of the must

4. the allowed amount of chaptalization

5. the earliest and latest picking dates

Once I was involved in the harvest, the process and the reasons for these regulations became clearer. 2012 has been a challenging year due to many factors including severe winter frost, spring frosts, hail and cold weather during flowering, and a very wet spring and summer resulting in severe outbreaks of powdery and downy mildew. All of the above have played havoc with the potential yields and because of this the total harvest is expected to be about 26% lower than average.

Once I was involved in the harvest, the process and the reasons for these regulations became clearer. 2012 has been a challenging year due to many factors including severe winter frost, spring frosts, hail and cold weather during flowering, and a very wet spring and summer resulting in severe outbreaks of powdery and downy mildew. All of the above have played havoc with the potential yields and because of this the total harvest is expected to be about 26% lower than average.

This year, the production has been set to 11 tons per hectare; last year it was 13.5 tons. This figure is based on the average yields out in the field as well as market requirements—and vignerons (growers) are encouraged to make the appellation requirements, as payments for the grapes are calculated accordingly.

Every year, the rules stipulate the appellation production as well as the amount which can be used as Réserve Individuelle (RI) or personal reserve wine for each champagne producer. In 2012 1000 kg on top of the 11,000 may be harvested and added to the RI—but very few people will have enough grapes to meet the absolute allowed maximum of 12,000 kg (12 tonnes) per hectare. In fact, all the people I have visited and spoken to (at Champagne Jacquesson, Champagne Tarlant, the co-operative Goerg, Champagne Jean Bliard and Champagne Philippe Gonet) will have to dig into their RI to make up the appellation quota. They can do this by unblocking reserve wine which they had accumulated in previous years.

Though the yields are relatively low, the fruit has ripened well thanks to a dry and hot August and September, so the average alcohol percentage for the must for 2012 has been set to 9.5%. This is quite high in comparison with other years when it tends to be closer to 8% or 8.5%. The alcohol percentage is measured in the pressed juice which makes up the cuvée. The amount of sugar one can add to the must this year has been set to 2%, or 3.36 kg/hl. However, as most musts at the wineries I visited have had an average of more than 10.8%, chaptalization will not be needed. The aim is to make a base wine with alcohol around 11%, resulting in a Champagne around 12% alcohol.

The earliest picking dates are decided per village (commune) by a committee made up of growers who taste and test the sugar levels in the grapes in several vineyards in the village. In general, the latest picking date is 21 days after the earliest picking date, however as there was quite a bit of variation in the average ripeness (due to the uneven flowering period) the CIVC decided this year to allow for a harvest period of 28 days. The last day of pressing has been set for the 28th of October, which is pretty late.

Other harvest regulations (which do not change from year to year) describe the maximum yields in liters. Per 4,000 kg of grapes, one is allowed to press up to 2,550 liters of wine. One needs to separate the first 2,050 liters (la cuvée) from the last 500 liters (la taille). And in practice, the first 50 liters of free-run juice is kept separate as it often includes quite a few impurities — especially this year where a lot of pesticides, copper and sulfur have been used. The rebêches (the must which is extracted after the 2,550 liters) may not be more than 2% in 2012. This last juice either goes to a distillery together with the grape skins, pips and stalks where it will be fermented and distilled into Marc de Champagne, or it can be used for the production of Ratafia. Either way, the rebêches—just as the cuvée and the tailles do—have to be recorded and declared in the carnet de pressoir (press ledger), which this year has to handed over to the CIVC by the 2nd of November.

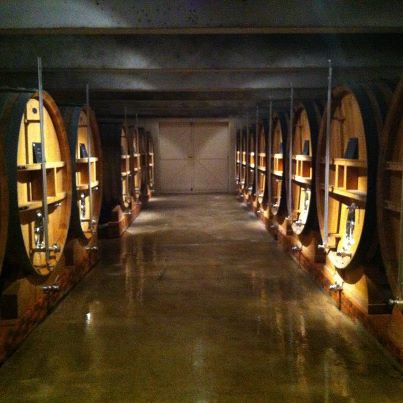

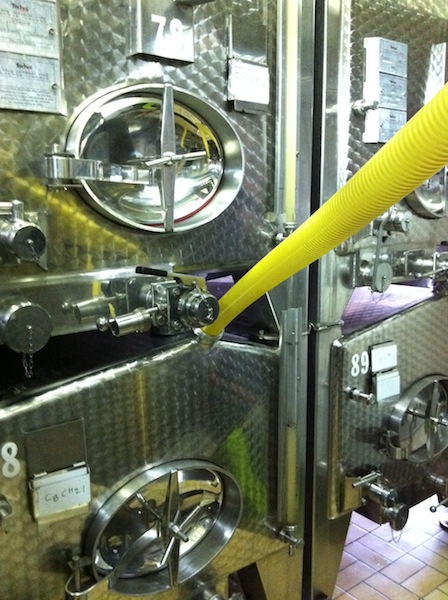

Different presses are used in Champagne, but the most common size I saw was a 4,000 kg press manufactured by Coquard. The larger establishments have 8,000 kg presses (often pneumatic) and smaller growers sometimes have 2,000 kg presses. Quite a few houses, including Jacquesson, still use the traditional basket press (square or round) but more and more establishments have switched to the modern presses. One common denominator is that the pressing must be extremely gentle in order to obtain as clear a juice as possible. The musts are often allowed to settle overnight and are racked off before they are put in the fermentation tanks or barrels.

As I write this, I am aching all over from bending over most of the day to pick grapes that are growing about two feet off the ground. But all in all I have really enjoyed my hands-on Champagne harvest experience. I enjoyed the atmosphere, the camaraderie in the field as well as in the press houses, and the generosity of the vignerons.

Furthermore, the quality of this year’s fruit is outstanding. Due to hard work in the vineyards all year—and some lucky late-summer weather—there is very little disease, the small yields have ripened evenly and the natural sugar levels are pretty high. All the juices I tasted at the different presses have been exquisite: they are well-balanced, with a great acidity, lots of concentrated flavors and enough sugar not to need chaptalization. Most winemakers and cellar masters believe 2012 has been a challenging year, but it has all the promise of a great vintage. I will be very interested to revisit and retaste a lot of the wines at the blending stage next spring.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/caro_twitter-e1337129825708.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Caroline is a wine educator as well as a wine marketing and social media consultant based in Champagne. She holds a WSET advanced certificate and is a certified sommelier studying for her advanced sommelier certificate. She has a particular interest in Champagne, terroir and natural wines and food and wine pairing. She blogs about all things wine related at Missinwine and Vinogusto[/author_info] [/author]