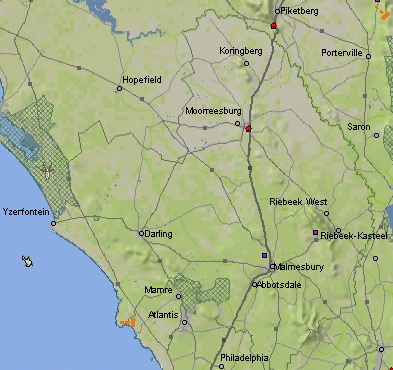

While South Africa is home to more than 600 wineries in over 90 appellations, a small group of maverick winemakers are stealing the nation’s spotlight, working with chenin blanc and Rhône varieties, off the beaten path in the Western Cape’s Swartland appellation. For those taking note, the noise rendered by this “wine revolution” is getting loud enough to challenge a pitch full of vuvuzela-toting football fans. Showcasing intense fruit, freshness, concentration, and elegant textures not found anywhere else in South Africa or, arguably, the world, Swartland wines consistently speak for themselves—even though the winemakers also have a lot to say.

So how does a nation making wine since the 1600s suddenly give rise to a whole group of visionary winemakers, in a region dominated by cooperatives producing high yield, chart-tipping alcoholic wines?

As I moved around Swartland, during a recent trip, winemakers unveiled treasure troves of R120-R200 (app. $17-$30) wines, with a few deservedly pushing R400 ($60). They were made using combinations of traditional and natural vinification methods to create the region’s signature marriage of freshness and texture. They have been resuscitating old chenin and grenache bush vines, dusting off decades-old large cement and wood tanks, weeding, pruning, and caring for long-abused vineyards, and then intervening as little as possible with the fruit in the vineyard and juice in the cellar. Not to be overlooked, the Swartland crew feeds on a vision fueled by collective energy. They reassure each other while experimenting with styles that show a restraint and authenticity not traditionally seen in current day South Africa. And they do so at prices that are values in their own right, while challenging the R50-R80 sensibility held by most South African wine consumers apparently willing to settle for overly extracted, tannic, high alcohol wine.

The answers to the Swartland mystery are wrapped in natural, economic, and human imperatives.

Nature

The fact that South Africa lies south of the Equator is not inconsequential to the spirit that animates the core group of Swartland wine makers. The Southern Hemisphere provides an unobstructed seasonal opportunity to work in Northern Hemisphere winemaking regions with non-conflicting growing calendars. France’s Rhône Valley and Languedoc, as well as some parts of California, are closely linked to Swartland’s weather and varietal suitability. Every wine maker I met spent time working and learning in these regions; Adi Badenhorst with Alain Graillot in Crozes-Hermitage, David Sadie with Yves Cuilleron in Verlieu, Chris Mullineux in Cote-Rôtie, the Languedoc, and in the US with Manfred Krankl of Sine Qua Non; the list goes on.

Even drier and hotter than close by Paarl, Swartland sees daytime summer temperatures pushing 40°C with inconsequential rainfall. The best winemakers avoid any irrigation and accept the terrain for what it offers. None of the local winemakers work with sauvignon blanc, cabernet, or merlot, popular in other Cape appellations. Instead, they have chosen to work with grape varieties more suited to their climate and soils. Depending on location, soil types range from schist to granite to clay. Chris and Andrea Mullineux source from 21 different vineyard sites to make their Mullineux and Kloof Street wines, and Chris says the range of site and soils helps them create final blends that leverage the advantages of “Northern Rhône-like schist for structure and tannin, granite to provide freshness, and clay to fill out the mid palate.” This strategic blending produced enviable mineral, acidic, and creamy outcomes in the full range of chenins I tasted, from Badenhorst’s entry level Secateurs through Craig Hawkins’ tiny production Testalonga.

The inarguable centerpiece story behind Swartland’s advantaged vineyard sites are its old vines. South Africa has a significant problem with grapevine leaf roll disease that eventually impedes quality and yield. It has forced replanting in cycles shorter than 25 years. According to Mullineux, “the sandy soils in Swartland makes it harder for leaf roll virus to spread.” It has spared the 35-60 year old chenin blanc and grenache vines originally worked for high-yield production by brandy distillers. The vines remained, but even with the emerging Swartland crew now grabbing their share, almost “90% of the 35+ year old chenin fruit still goes to local co-ops,” according to Badenhorst.

This gave savvy winemakers an opportunity to make their move. If you ask Badenhorst why he decided to purchase his Kalmoesfontein farm in Swartland back in 2007, he will tell you with a knowing grin that “it was cheaper and [Swartland] is less up your ass than Stellenbosch” where larger production wineries and status quo winemaking practice prevails. Badenhorst adds that he was enlightened by his exposure when “I bought fruit from here in Swartland while I was making wine for Rustenberg” in Stellenbosch. Mullineux also previously made wine up in Tulbagh and bought Swartland fruit for Tulbagh Mountain Vineyards. David Sadie grew up in Swartland and purchased fruit there before launching his own brand called David. And it didn’t take long for Craig Hawkins, a modern day 29 year-old combination of cellar artist and mad scientist, to see what could be accomplished working with Eben Sadie before he dialed into Lammershoek and his own Testalonga label.

The combination of Swartland’s terroir and old vines combined with underlying farming economics to instigate the Swartland revolution.

Economics

Traditional Swartland growers have suffered financially from an inability to leverage the potential of their old vines, as they were selling to co-ops only willing to pay $200-300 per ton from vines that are, at their best, yielding less than 4-5 tons per hectare. Improper vineyard care compounded the problem, and old vines either died off or experienced exaggerated yield shrinkage from the neglect. Mullineux comments that “it was simple for the co-ops to produce super ripe wines at 14.5%-15% alcohols, but at richness levels inaccessible to most drinkers.” Land became cheap to buy if you were willing to reclaim and revive the vines, and fruit contracts were easily secured by “revolutionaries” willing to pay three to four times more per ton than coops offered. Swartland’s new winemakers were willing to work with growers in the vineyard to get the fruit they needed, in order to make artisanal wines that could be priced accordingly. “We can pick earlier for greater freshness, but the wine still has its richness.”

Anxious pioneers connected with established growers and helped them manage choice rows and vineyards of old vines to produce proper yields and attractive economics for both growers and winemakers. The ready source of fruit that could be acquired in small pieces greased the wheels for these new winemakers with small production agendas. David Sadie (no relation to Eben Sadie, a well-known winemaker who also emerged from Swartland) credits this dynamic for allowing him to bottle under his own label while simultaneously working and making wine at Lemberg.winery, found further north at one of the highest altitudes of the Swartland appellation. Mullineux was able to launch from a small winery in the town center of Riebeek Kasteel, without any farmland to call his own, because he also paid the right money to make it financially attractive for growers to slice up their farms into vineyards and rows selected for Mullineux.

If Franschoek’s Boekenhoutskloof Winery’s recent acquisition of Swartland’s boutique Porcelain Mountain winery’s a precursor to more land grabs, those attractive contracts might be tougher to come by in the near future. In a recent Daily Mail interview, Mark Kent of Boekenhoutskloof admitted, “bank robbers rob banks, because that’s where the money is; we’re getting more involved in the Swartland, because that’s where the quality is!”

But it does not come without work. Adi Badenhorst bought his farm in disrepair. The old chenin vines were yielding 1.5 tons per hectare that he has pushed to almost 4 tons without any sacrifice to quality, he says. He found weed control was key, as well as crop rotation between vines. He does not focus on strict organic farming, claiming organic sprays require 12-14 applications per year and thus increasing the carbon footprint in the vineyard. Badenhorst sprays about four times a year. The practices have driven incremental yield gains from 1.5 tons to 2.5 tons to 3.5 tons for the old vines during the vintages under his care. Mullineux gets his hands and boots dirty in a cross section of his 21 vineyard sources, determining involvement as required by vineyard.

The new economics unfurled a red carpet for winemakers filled with vision, authentic wine making orientations, and risk tolerance. Swartland’s growth from five wineries ten years ago to almost thirty today smacks of a gold rush—but without the greed. “Swartland’s struggling farmers are now being looked after by the likes of Eben Sadie, Craig, Chris, and me who want to put juice in a bottle with an idea—not just to make wine,” says Badenhorst.

Human Element

Craig Hawkins, with thief in one hand and bucket in the other, excitedly jogged me around his closely guarded Lammershoek barrel room as if he was unveiling paintings in the studio or experiments in his lab. We tasted through an amazing range of wines including entry level Lam blends; Lammershoek Chenin, Syrah and Roulette; Craig’s own sulferless Testalonga wines made from whole bunches including stems, skin fermentation, and part carbonic maceration, featuring El Bandito which is a white wine made like red wine. After that, it was simple to see Craig’s edgy genius and enthusiasm infused in all the wines. Low alcohols, richness and good acidity were consistent combinations. “I like wines naked and residual sugar is like make up,” said Craig. He feels his ability to craft these wines is built on an understanding that “the biggest thing is picking on taste … knowing when to do nothing … forgetting about recipes.” While Craig knows that world perception of South Africa wines has to change, he admits “it must change here first.” And he is doing everything he can to lead the way.

The region’s dynamic and purposeful personalities are already driving growing global recognition. “Swartland is better known outside of South Africa than inside … we are farming an unknown region,” says Mullineux. “We have to stick together. It is a sharing and open community and we all realized together that we can make a certain style of wine by being collaborative. We constantly help each other with vineyard sourcing and the like. If I need more acidity in a particular blend, I can call one of the other winemakers and they will point me to a vineyard source.”

David Sadie gets it. “We don’t have to make a Chenin like it comes from the Loire … we are looking to establish identity and reputation first. We will worry about making money second.” And he may just be on his way. Shortly before my visit with David, Master of Wine Tim Atkin wrote favorably about David’s Chenin Blanc, Viognier and Verdelho blend Aristargos, and ten of the fifty case production was already on its way to meet ignited UK consumer demand. “I wish I could be with Adi, Eben, and Craig down in the Paardeberg. I am up here in Tulbagh for now … I can start this way,” Sadie says recognizing the pioneering benefits of tight collaboration. Still, up on the hill on his own, he is making remarkable wine for both Lemberg and his David label.

I am convinced that without the energy of these new South African revolutionaries, the shale, granite, old vines and low yields would have stayed in the shadows of this wine region. But thanks to the likes of Adi Badenhorst—who has enough irreverence for the status quo to state publicly that he would rather “watch Jerry Springer and chew his toenails than drink a glass of Sauvignon Blanc”—Swartland has turned into a center of winemaking energy that will not escape global notoriety for long.

•••

Here are some Swartland wineries to look for and pay attention to:

Badenhorst Family Wines www.aabadenhorst.com, adi@iafrica.com

David www.davidsadie.co.za, wine@davidsadie.co.za

Lammershoek www.lammershoek.co.za, carla@lammershoek.co.za

Mullineux www.mullineuxwines.com, info@mullineuxwines.com

Sadie Family Vineyards www.thesadiefamily.com, office@thesadiefamily.com

Adam Japko fell in love with wine 25 years ago growing up in New York City and has been collecting and promoting wine as a lifestyle component ever since. Since getting his journalism degree from NYU in 1979, he has made his career as a magazine executive and is currently president of a group of luxury media brands at Network Communications, Inc., where he has been helping his company reshape traditional media models in a fast-changing world of free quality content and social media. He regularly writes about wine at his blog Adam Japko’s WineZag.