I was in Cognac one hot summer day, trying to make conversation with a producer who spoke about as much English as I do French, and the situation was getting sticky in every way when he suddenly asked me whether I had been to Scotland.

Yes, I had.

Well, then, he asked, how did I feel about haggis.

Well, then, he asked, how did I feel about haggis.

“I LOVE it,” I replied. “It’s the perfect pairing for whisky.”

“Madame,” he said. “It’s the only reason to drink whisky.”

I would not go quite that far but I do feel that haggis is a sadly misunderstood comestible.

The name doesn’t help – Is that a disease or a dish? – and no one can claim that the product in its natural state is a beauty.

And then there’s the offal truth of what goes into haggis, at least in the traditional recipe – sheep’s pluck, which is not about spunky sheep but rather refers to the heart, liver and lungs. Recipes vary, but often the meat is minced with onion, oatmeal and suet (animal fat) and is mixed with stock and spices and baked as a kind of sausage, or savory pudding. Back in the day, the casing was the sheep’s stomach, conveniently to hand, but modern haggis comes in artificial casings.

And it is delicious!

Shaped into balls, artfully sculpted or just slapped on to a plate, haggis is pretty much a heat-and-eat type of food. It is nearly always served with tatties and neeps, tatties being mashed potatoes, and neeps referring to turnips, although in this case it’s a yellow turnip know to us as rutabaga in the United States. (In Britain the vegetable is called a swede, from Swedish turnip. And, bonus trivia, rutabaga is actually, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, a corruption of the Swedish word rotabagge, from rot (root) + bagge (short, stumpy object).

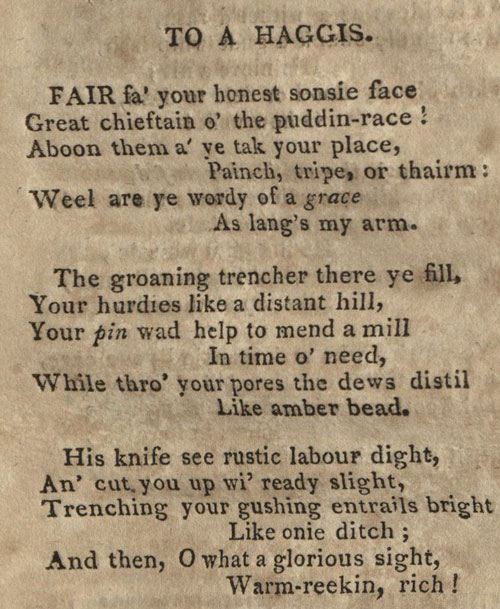

According to Macsween, a major producer of the delicacy, it’s not a particularly Scottish dish in origin but became one after the 18th-century poet Robert Burns wrote his eight-verse “Address to a Haggis,” which cemented the link.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race!

OK, then.

Burns and haggis get a big night out once a year with Burns Suppers held in honor of his birthday, Jan. 25, at which a great deal of haggis and whisky is consumed.

But of course you don’t have to wait until then. You can’t buy Scottish haggis made in the traditional way in the U.S. due to a prohibition on importing sheep lungs. It’s not illegal to make haggis, so you can find it at adventurous restaurants that make their own. Imported haggis is available online from a company called Scottish Gourmet USA although their version substitutes ground beef liver for sheep’s lung.

Yum.

If you are thinking of having a little haggis and whisky, just about any good dram will do. You might try The Macallan 12-year-old Sherry Oak, smooth, refined, dried fruit and warm caramel flavors enlivened by a kick of ginger. Or the Glenfiddich 12-year-old is also a good choice, a classic Speyside single malt, fruity with some floral notes, I thought it picked up the neeps nicely.

If you are into the peat, Laphroaig Lore, the Islay distillery’s “No Age Statement” release for 2016, is a distinctive whisky that can hold its own with equally distinctive haggis. The pairing has the blessing of Simon Brooking, master brand ambassador for Laphroaig, who finds “the incorporation of layered maturations of Laphroaig Lore adds to the complexity of robust flavors that marry with the spices and sweetness of haggis, enhancing the flavor of the gamey meat.”

Lore starts with an assertively peaty nose and as the whisky hits your palate, the peat continues to come on strong — rich, oily, smoky. But wait a few seconds and honeyed spices begin to develop for a lingering and sweet aftertaste.

Now all you need is haggis.

Or, as Burns puts it:

And then, O what a glorious sight,

Warm-reekin, rich!