North Carolina’s first commercial winery was established in 1835 by Mr. Sidney Weller, in the community of Brinkleyville, in Halifax County.

But that wasn’t the beginning.

In 1584, Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, exploring on behalf of Sir Walter Raleigh, came upon a land they described as “…so full of grapes…that I thinke in all the world the like abundance is not to be found.” Before them, in 1524, Spanish conquistador Giovanni de Verrazzano saw the coast of North Carolina and described “many vines growing naturally…[which] would doubtless yield excellent wine…”

And it did.

Evidence suggests that before the Europeans sailed the ocean blue, native populations – specifically, the Croatoans – were already making wine from North Carolina’s native grapes. The “Mother Vine” – an immense, 32-feet-wide by 120-feet-long Scuppernong plant – is thought to be the direct descendant of this ancient viticulture. At 400 years old, she is the oldest cultivated grape vine in the country (some say the world), and many vineyards across the United States have her to thank for their creation.

Although those first winemakers, and the colonists with them, mysteriously vanished in the late 1580s, nearly three hundred years later, in the 1850s, almost twenty-five wineries were registered in the state. Mr. Weller’s little vineyard, (by then renamed Medoc Vineyards), actually led the country in wine production. The Civil War wiped out the industry in the 1860s, but by the end of the century, North Carolina’s wine industry was thriving again, and the state’s wines even won medals at the Paris Exhibition of 1900.

In case you missed that last part, it bears repeating: Long before the 1976 Judgment of Paris, North Carolina wines were already receiving accolades in France.

The winning wines were not Cabernet Sauvignon or Chardonnay. Experiments with those grapes – varieties of the European species Vitis vinifera – had been pursued and later abandoned, as with Swiss native Eugene Morel, who, “persuaded a group of French settlers to join him [in planting] 100,000 cuttings of aramon, mourvèdre, grenache, carignane, cinsaut, mourastel, and clairette vines [at his vineyard near Ridgeway, North Carolina].” Succumbing to challenges that ran the gamut from unfamiliar New World vine diseases to weather, the project was deemed a failure just five years later.

The wines of the day were made from native and hybrid varieties. Grapes like the Vitis rotundifolia species (the muscadines, like The Mother Vine’s scuppernong), and Vitis labrusca (catawba, concord) were the ones that took hold in Southern soil – and really took off.

At least until Prohibition.

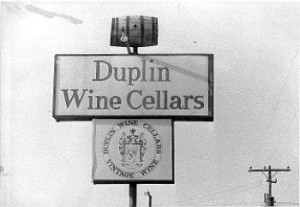

Virginia Dare, the most popular American wine in the country at the time, hailed from the Old North State, but that didn’t keep North Carolina from jumping on the wagon in 1909. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed in 1933, but the state waited two more years before overturning the ban. The finishing blow to the industry came in 1947 when 100 counties voted dry, and the last of North Carolina’s thirteen wineries finally gave up the fight, and shut down.

Boomtown, NC

Meanwhile, up in the quiet mountain community of Asheville, sat the 8,000-acre Vanderbilt family home called the Biltmore Estate. A “locavore” before it was cool, George Vanderbilt had a vision to create a self-supporting property, where everything used on the estate would come from the estate, from wood hewn from Biltmore trees; to bricks made in the Biltmore brick factory; to food grown, raised or hunted on the grounds. It was Biltmore’s grandson, William A.V. Cecil, who took this idea to the next level in 1971, planting grapevines on the property to satisfy the family’s thirst for wine. French-American hybrids went in first; vinifera followed in the next few years. In 1979, the Biltmore Estate sold its first bottle.

By then, the state’s anti-alcohol attitude had finally begun to change. North Carolina was starting to see an influx of real money from supplying wine grapes to the rest of the nation, and several organizations had been founded to support the tentative first wingflaps of an industry many hoped would grow strong and soar.

In 1985, the Biltmore Estate opened their $6.5 million winery to the public. It is now the most visited winery in the country.

Quietly, under the radar, the rest of the North Carolina wine industry is starting to catch up.

Michael Helton, winemaker and co-owner with his wife, Amy, of Hanover Park Vineyard, has witnessed the transformations first-hand. “When I came to this state in 1989, there were five wineries, and I became the sixth. And in that first decade, the growth went from six wineries to fifteen. From 2000 – 2010, it went to 100. And now there’s probably 110 or so and they’re opening at a rate of one per month.”

Crossing The Mason-Dixon

How does a wine region experience a 1733% growth increase without causing ripples like tsunamis across the rest of the industry? In this case, there are reasons aplenty. Unless you’re local, or one of the snowbirds who make their way down the pipeline from Ohio through North Carolina to Florida every year, it’s likely the only exposure you’ve had to North Carolina wine would be sporadic, if at all. While the Biltmore Estate, itself, is known across the nation, many who are familiar with the property do not associate it with winemaking, and of those that do, most of those consumers are not expanding their local purchases beyond the brand.

Incidentally, currently many of the grapes used to make Biltmore Estate wine are shipped in from elsewhere. The reason for shipping in fruit? As Mr. Morel discovered, vinifera struggles to grow, but the vinifera varieties are the ones people recognize – the ones that sell.

At the recent North Carolina Winegrowers Association conference in Winston-Salem, Dr. Sara Spayd, Extension Viticulture Specialist and Professor from NC State University’s Department of Horticultural Science, led a seminar on grape varietals and their growth success in the state. She ticked through slide after slide of the challenges to growing the species in NC. Chardonnay: early budbreak is lost to frost; cabernet sauvignon:light on color and tannin; cabernet franc:can be vegetal; zinfandel: “recommended for experienced growers only;” muscats: simply don’t grow, and rot with 7 inches of rain per year — with North Carolina’s 30 – 50 inches? “no way.” Syrah: shy bearer. She also warns, “I’ve seen syrah go from 21 brix to 28 brix in three days,” after shriveling. Merlot, riesling, pinot noir: too hot. Of sauvingon blanc, she simply reports, “Not for the faint of heart.” Dr. Spayd praises viognier for making “a beautiful wine in North Carolina. Really beautiful,” but goes on to say that it, too, is a shy bearer, and “until we work out the yield issues,” she can’t recommend it.

At the recent North Carolina Winegrowers Association conference in Winston-Salem, Dr. Sara Spayd, Extension Viticulture Specialist and Professor from NC State University’s Department of Horticultural Science, led a seminar on grape varietals and their growth success in the state. She ticked through slide after slide of the challenges to growing the species in NC. Chardonnay: early budbreak is lost to frost; cabernet sauvignon:light on color and tannin; cabernet franc:can be vegetal; zinfandel: “recommended for experienced growers only;” muscats: simply don’t grow, and rot with 7 inches of rain per year — with North Carolina’s 30 – 50 inches? “no way.” Syrah: shy bearer. She also warns, “I’ve seen syrah go from 21 brix to 28 brix in three days,” after shriveling. Merlot, riesling, pinot noir: too hot. Of sauvingon blanc, she simply reports, “Not for the faint of heart.” Dr. Spayd praises viognier for making “a beautiful wine in North Carolina. Really beautiful,” but goes on to say that it, too, is a shy bearer, and “until we work out the yield issues,” she can’t recommend it.

That’s not to say that some people aren’t growing vinifera – and growing it well. In fact, some North Carolina Old World wines are taking home honors in international competitions. RagApple Lassie was one of two finalists in The Wine Appreciation Guild’s “Best New Winery in the USA,” and in 2003 their Chardonnay won “Best of Show.” At the 2011 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition, Biltmore’s estate-grown Sparkling Blanc de Blancs earned “Best of Class,” and their Reserve Chardonnay took home gold. Wine Business Monthly magazine named Raffaldini Vineyards one of their “Top Ten Hot Small Brands in North America” in 2009.

Dana Acker, winemaker for Windsor Run Cellars, is confident the awards will keep coming. “People are growing smarter. They’re pulling up things that didn’t work. We know what to do with the soil now, we know what to plant now – we know what not to plant now.” Then he adds, “I think the next ten years will be vastly different from the past ten years.”

The vines he’s referring to – the grapes he feels will put NC squarely on the map – are hybrids like traminette, chardonel, seyval blanc and chambourcin; and American grapes like lenoir (Vitis aestivalis), norton and the muscadines. Acker even admits, “If I were going to plant a vineyard today, I’d plant nothing but hybrids.” They’re resistant to many of the diseases that plague the European grapes, and cost about 60% less to maintain. Not only that, but they’re producing some really impressive wines.

This isn’t really news to the locals. As discussed extensively over the 3-day conference, many North Carolinians are raised on muscadine grapes, and muscadine wine triggers childhood nostalgia about picking and eating wild grapes off the vine, or enjoying sandwiches made from peanut butter and scuppernong jelly. The memories, alone, have kept local wine sales steady.

But non-natives tend to be a little more skeptical – not just about the more unfamiliar varieties or of giving hybrid varieties a fair chance – but also about the fact that muscadine wines are often sweet. That sweetness is both a blessing and a curse: sweet wines (including many fruit wines, which are common in the state) pay the bills, but they also hinder respectability. Earning respectability is another reason vineyards are taking advantage of modern technology to grow vinifera along with natives and hybrids.

Steve Shepard, general manager and winemaker for RayLen Vineyards and President of the North Carolina Winegrower’s Association sees vinifera as a foot in the door for wider audiences. “If you can make a Cabernet Sauvignon like what they’re used to, then you can get their attention and you can introduce them to something they’ve never heard of.”

State of the State

Apparently, more and more people are willing to expand their vinological horizons.

The first North Carolina Wine Festival was held in 2001, and by the next year, there were 11,000 people in attendance. Currently, the state and her three AVAs rank 7th in US wine production, and the industry is experiencing a $1.5 million economic impact. In July of 2009, President Obama presented Italian President Giorgio Napolitano with a basket of American wines, including a Vermentino from Raffaldini Vineyards; and RayLen Vineyards was featured on the “Today” show in December 2011.

The first North Carolina Wine Festival was held in 2001, and by the next year, there were 11,000 people in attendance. Currently, the state and her three AVAs rank 7th in US wine production, and the industry is experiencing a $1.5 million economic impact. In July of 2009, President Obama presented Italian President Giorgio Napolitano with a basket of American wines, including a Vermentino from Raffaldini Vineyards; and RayLen Vineyards was featured on the “Today” show in December 2011.

There are hurdles to overcome, but there is a genuine roll-up-your-sleeves-and-get-dirty excitement, and it’s drawing professionals away from more comfortable positions in more established wine regions. Even Dr. Spayd, bleak as her slides might seem, came back to North Carolina after working at Washington State’s Enology program for 26 years. She says she wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.

RayLen’s Steve Shepard cut his teeth on vineyards in Pennsylvania before moving south. Raffaldini winemaker Kiley Evans earned a double major in Viticulture and Enology from California’s UC Davis and then spent time making wine in Oregon. Dr. Seth Cohen, Director of the brand-new Appalachian State University Enology program, is also a recent transplant from Oregon. Like the others, he’s energized by this Wild West of wine. “The research concerns in a more established wine region are more economic- or market-driven, rather than an industry in its infancy, where people are understanding the research that’s been done, to help them make or improve the quality of their wine on a very basic level.”

With that research at their disposal, a tight-knit community willing to work together to raise the bar, and increasing notoriety, the industry seems to be the Not-So-Little Engine That Could. They’re battling harvest time in the middle of hurricane season and other natural hurdles – but they seem to be slaying these dragons – or at least dealing with them – at a meteoric clip. It might’ve taken North Carolina wine 400 years to really come into its own, but by all accounts, that momma on Roanoke Island can proudly say her baby is all grown up.

Arianna snacks, sups, sips and swallows – and lives to write about it. Always hungry for food adventures, she stays thirsty for wine and the occasional quality cocktail, as well. When she isn’t buried in her laptop or chasing after a food truck, she’s taking her son on adventures across Los Angeles and opening his mind to the amazing beauty of the world, its people, and the universality of coming together over a good meal. You can read more about her delicious escapades at GrapeSmart.net, MutineerMagazine.com, FoodTruckTimes.com and other assorted fine websites.

Arianna snacks, sups, sips and swallows – and lives to write about it. Always hungry for food adventures, she stays thirsty for wine and the occasional quality cocktail, as well. When she isn’t buried in her laptop or chasing after a food truck, she’s taking her son on adventures across Los Angeles and opening his mind to the amazing beauty of the world, its people, and the universality of coming together over a good meal. You can read more about her delicious escapades at GrapeSmart.net, MutineerMagazine.com, FoodTruckTimes.com and other assorted fine websites.