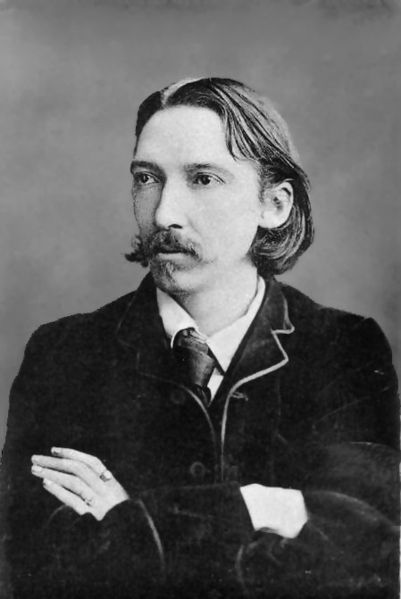

Robert was a visitor to the Napa Valley who was so interested in the region’s wine that he wrote about it in detail.

And no, his last name wasn’t Parker.

Long before the rise of modern wine writing, Robert Louis Stevenson brought a connoisseur’s eye to California’s nascent wine industry when he honeymooned in the valley in 1880.

His book, The Silverado Squatters, is based on his diary from that period and includes a chapter on Napa that begins with this quote: “I was interested in Californian wine. Indeed, I am interested in all wines, and have been all my life, from the raisin wine that a schoolfellow kept secreted in his play-box up to my last discovery, those notable Valtellines, that once shone upon the board of Caesar.”

The Valtelline Valley, known for fine Nebbiolo, is in Italy, but Stevenson was also familiar with France, then still in the throes of the phylloxera blight that scourged vineyards across Europe. “Chateau Neuf is dead and I have never tasted it,” he writes poignantly.

But if France was in ruins, there was hope, Stevenson thought, in the New World. “A nice point in human history falls to be decided by Californian and Australian wines,” he wrote.

Stevenson, who had been traveling the world, was in Northern California to marry his beloved Fanny, then living in Oakland. They started their honeymoon in a Calistoga hotel but were dismayed by cost (the going rate was a princely $10 a week) and decamped to a run-down but free cabin in the abandoned Silverado Mine. If you visit the site of the long-vanished mining camp in Robert Louis Stevenson State Park, you may feel a sense of déjà vu; the rugged terrain served as inspiration for the setting of Treasure Island, published a few years later to much acclaim.

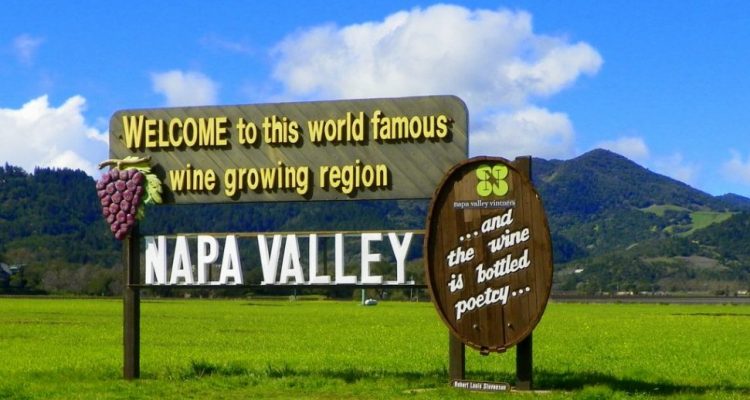

During his stay, Stevenson visited a few wineries, including the still-surviving winery founded by Jacob Schram, Schramsberg, now a producer of fine sparkling wine. Valley vintners were still at the experimental stage, and Stevenson saw the new vine plantings as prospecting for buried treasure — “bit by bit, they grope about for their Clos Vougeot and Lafite.” Still undiscovered, he wrote, were those kind of spots where “the wine is bottled poetry,” a famous quotation that is commemorated on the welcome signs at the north and south ends of the Napa Valley. Stevenson, of course, was talking about the region’s potential, not delivering a five-star review, but it’s clear he was confident the attempt would be successful, declaring that, “The smack of Californian earth shall linger on the palate of your grandson.”

But back then marketing California juice was a challenge. A San Francisco wine merchant showed Stevenson shelves of California wine that had been mislabeled as coming from Spain to persuade a skeptical public they were worth drinking.

As it turns out, Stevenson’s eulogy for French wine was a bit premature. Around the time of his writing, viticulturists were figuring out that the sap-sucking insect phylloxera, which had spread from the New World to France, could be defeated by grafting Old World vines on to North American rootstock.

But he nailed the ultimate rise of the Napa Valley and even went so far as to note that hillside vineyards were likely to prosper, poetically declaring that the “grossness of the earth must be evaporated, its marrow daily melted and refined ….”

And he did his share of tasting, including working his way through “every variety and shade of Schramberger,” which back then included red, white and “Golden Chasselas,” a grape now most closely associated with Switzerland.

Speaking of California wine quality overall he rated it as “merely a good wine,” with the best being better than, and not unlike, Beaujolais.

The record does not show how many points he gave that wine.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/me-at-Absinthe.jpg [/author_image] [author_info]Michelle Locke is a freelance lifestyles writer based in the San Francisco Bay area. She blogs at Vinecdote.[/author_info] [/author]