“There is an alcoholic haze at the center of our galaxy.”

No, that sentence isn’t an example of fuzzy-headed navel-gazing after a night of over-imbibing. It is an excerpt from Dr. Patrick E. McGovern’s 2009 book “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages,” and it refers to the huge clouds of methanol, ethanol and vinyl ethanol that exist in space—one of which stretches near the center of the Milky Way. It is hypothesized that this vinyl ethanol, contained in dust particles and frozen into comets, may have introduced the first building blocks of life on Earth. If that is the case, is it any wonder human civilization developed from the start with a drive to create—and consume—fermented beverages?

No, that sentence isn’t an example of fuzzy-headed navel-gazing after a night of over-imbibing. It is an excerpt from Dr. Patrick E. McGovern’s 2009 book “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages,” and it refers to the huge clouds of methanol, ethanol and vinyl ethanol that exist in space—one of which stretches near the center of the Milky Way. It is hypothesized that this vinyl ethanol, contained in dust particles and frozen into comets, may have introduced the first building blocks of life on Earth. If that is the case, is it any wonder human civilization developed from the start with a drive to create—and consume—fermented beverages?

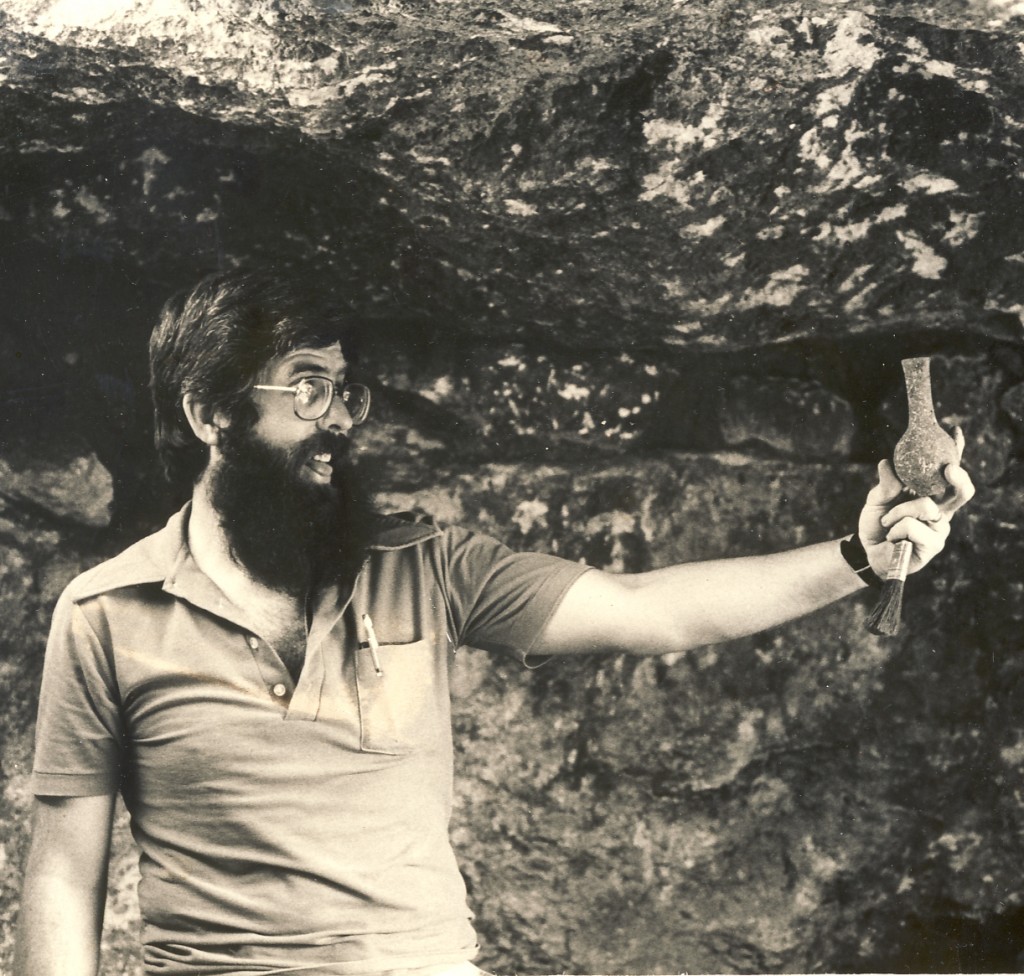

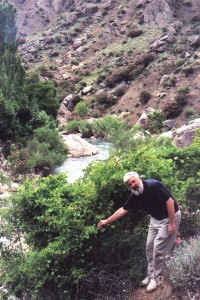

McGovern (prepare yourself for the best job title ever) is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. He began his archaeological career as a student of pottery. Later, fascinated by the idea that new technology could potentially identify beverage residues often found inside excavated vessels, he became a pioneer in the field of analyzing these chemical fingerprints, which led to the discovery of the earliest-known fermented beverages from a variety of cultures. McGovern recently presented a lecture at the Getty Villa in Malibu, CA, where he illuminated his findings in a combination of archaeological discovery; scientific investigation; and the study of ancient texts and art, demonstrating the historical importance of alcohol in human culture, society and religion.

“Life is based on fermentation,” McGovern said. While the statement can be interpreted literally (it is believed that glycolysis—sugar fermentation—was the first form of energy production for life on Earth), it also speaks to the broader fact that nearly every single creature on the planet—from fig wasps, to elephants, to modern-day humans clinking crystal goblets—is attracted to the alcohol that results from the natural fermentation of yeast and sugar. The oldest discovered alcoholic beverage residue, from 9,000-year-old vessels unearthed at a gravesite in Jiahu, China, proves our forebears were both innovative and reverent in their creation and use of local “grog.”

China: An Ancestral Beginning

Tartaric acid. C15H31COOC30H61, otherwise known as beeswax. Phytosterols indicating a temperate-climate grain such as rice. These sterile-sounding compounds were all that remained in ancient jars, buried with the dead in Jiahu to ensure a well-sated afterlife. What the jars ensured, as well, was that many thousands of years later, we would gain keen insight into the way past cultures interacted with both their deceased and their fermented beverages.

Tartaric acid. C15H31COOC30H61, otherwise known as beeswax. Phytosterols indicating a temperate-climate grain such as rice. These sterile-sounding compounds were all that remained in ancient jars, buried with the dead in Jiahu to ensure a well-sated afterlife. What the jars ensured, as well, was that many thousands of years later, we would gain keen insight into the way past cultures interacted with both their deceased and their fermented beverages.

The buried beverage, analyzed via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS); carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis; and infrared spectrometry, was determined to contain a mixture of native-grape and hawthorn-fruit wine (the tartaric-acid component), honey mead (the beeswax component), and rice beer (the grain component). This finding marked the earliest use of grape as an ingredient in a fermented beverage anywhere in the world. After he examined the carved-bone flutes found in the grave, and studied writings reflecting the time, McGovern ascertained that the beverages were merely one part of an intricate religious funeral ceremony involving music, food, dance and divination, with consumption of the local mixed-fermented beverage a crucial aspect of connecting the mortal and the spirit worlds.

Turkey: The Midas Touch

Whether the hermetically sealed royal tomb discovered in 1957 in Turkey, dubbed “the Midas tumulus” and dated to 750-700 BC, actually belonged to the real-life King Midas, or his father, or his grandfather, one fact is certain: It contained more Iron-Age drinking vessels than any other site ever found. The room was filled with 157 bronze containers, many full of a bright yellow residue, which McGovern was keen to analyze.

Whether the hermetically sealed royal tomb discovered in 1957 in Turkey, dubbed “the Midas tumulus” and dated to 750-700 BC, actually belonged to the real-life King Midas, or his father, or his grandfather, one fact is certain: It contained more Iron-Age drinking vessels than any other site ever found. The room was filled with 157 bronze containers, many full of a bright yellow residue, which McGovern was keen to analyze.

This was the first ancient beverage McGovern and his team identified, and they were surprised at the results. “Phrygian grog,” McGovern dubbed it. The results proved this noble king was sent to the afterlife with many liters of a mixture of barley beer, grape wine, and honey mead—a blend that seemed undrinkable to the modern palate, accustomed to keeping beer and wine in their separate worlds. (“Never mix the barley and the grape,” my late grandmother admonished.) But later discoveries, such as the Jiahu site mentioned above, proved earlier civilizations had been crafting similar mixtures for many thousands of years. “If you’ve got it, ferment it,” seemed to be the spirit of the times, and discoveries in cultures to come would prove the ingenuity of using locally grown fruits, grains and other sugar sources to create alcoholic beverages.

Honduras: Chocolate, Wine and Blood

The smallish but mighty cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, is native to the tropics of Central and South America, and the Amazon. Its flowers are pollinated by midges, small flying insects whose work allows these flowers to grow into pods the size of an American football, containing a sweet, juicy pulp that—naturally—begins to ferment if a pod should happen to hit the ground and crack. Clay jars found in Puerto Escondido, Honduras, dating back to 1400 BC and analyzed in the lab by McGovern, held theobromine residues, proving that these people, like others proven throughout time to utilize native fruits for their fermented pleasures, made and drank a “chocolate wine.”

The smallish but mighty cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, is native to the tropics of Central and South America, and the Amazon. Its flowers are pollinated by midges, small flying insects whose work allows these flowers to grow into pods the size of an American football, containing a sweet, juicy pulp that—naturally—begins to ferment if a pod should happen to hit the ground and crack. Clay jars found in Puerto Escondido, Honduras, dating back to 1400 BC and analyzed in the lab by McGovern, held theobromine residues, proving that these people, like others proven throughout time to utilize native fruits for their fermented pleasures, made and drank a “chocolate wine.”

Just as the other beverages discovered and described above were a key component of cultural and spiritual activities, historical art and writings demonstrate that the cacao-based brew of South America—which was flavored with everything from honey, to flowers, to vanilla—also served as a form of liquid courage, celebration, and cultural touchstone. As South American culture evolved, the Mayan creation myth established humankind as originating from maize, sweet fruits and cacao. Later, Aztecs not only used cacao beans as currency, but also gave the cacao tree a central place in mythology, representing the ancestors and blood itself.

But, What Did They Taste Like?

If all this talk of fermented beverages has made you thirsty, well, you are not alone. Luckily, McGovern’s curiosity about ancient brews does not end with sheer academic analysis. Over the years, he has worked with Dogfish Head Craft Brewery in Milton, DE to actually re-create versions of the three ancient beverages mentioned in this story, based on the ingredients identified by decidedly 21st-century tactics.

Dogfish Head (motto: “Off-Centered Ales for Off-Centered People”) had a history of its own that dovetailed perfectly with McGovern’s quest. Founded as a small brewpub in 1995 by Sam Calagione, the company quickly began to invent, create and offer a head-spinning myriad of exotic brewed beverages. Brown ale made with beet sugar and raisins? It is a best-seller. A beer that includes a component from every continent—Australian ginger and South American quinoa among them? Why not?

Dogfish Head (motto: “Off-Centered Ales for Off-Centered People”) had a history of its own that dovetailed perfectly with McGovern’s quest. Founded as a small brewpub in 1995 by Sam Calagione, the company quickly began to invent, create and offer a head-spinning myriad of exotic brewed beverages. Brown ale made with beet sugar and raisins? It is a best-seller. A beer that includes a component from every continent—Australian ginger and South American quinoa among them? Why not?

“We’ve explored recipes and ingredients that encompass the whole culinary world,” Calagione said. “Working with the physical evidence of these ancient beverages was inspiring and exciting, to know factually what they really were, and extrapolate to come up with modern recipes.”

Those recipes include what Calagione calls “the biggest liberty we take” in his company’s commitment to maintain authenticity while recreating brews from thousands of years ago—the controlled, hygienic brewing environment. “We know what yeast we’re adding; we can control the process, which are things our ancient-brewing brethren were not able to do,” he said. “All ancient beverages probably were spoiled, in the context of today’s palate.”

Made possible by modern technology, the three recreated Dogfish Head beverages offered Getty Villa lecture attendees a millennia-spanning taste of Neolithic China; Turkey circa 740 BC; and Mayan royalty. The authenticity did not extend to fired-clay serving vessels—in another nod to modernity, plastic cups were the method of delivery—but it was truly fascinating to sip each creation and imagine its origins. (Tasting notes appear below.)

“Think of these beverages as liquid time capsules,” McGovern said. Under a steely gray sky, as whisper-soft rain coated the Edenic outdoor sanctum of the Villa, one could hardly help but allow the mind to wander, transported to faraway places and unknown times, all the way back to the primordial soup. After all, despite the vast differences among civilizations throughout history, one fact unites us: Since life began, we have been driven by the pursuit of fermentation—and its results.

TASTING NOTES:

“Chateau Jiahu,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from the oldest-discovered fermented beverage in history, found in 9,000-year-old drinking cups recovered from a burial site in Jiahu, China. A brew of brown rice syrup, orange blossom honey, muscat grape, barley malt and hawthorn berry. 10% ABV:

“Chateau Jiahu,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from the oldest-discovered fermented beverage in history, found in 9,000-year-old drinking cups recovered from a burial site in Jiahu, China. A brew of brown rice syrup, orange blossom honey, muscat grape, barley malt and hawthorn berry. 10% ABV:

A nose of honey and white flowers. On the palate, sweet upfront, with notes of honey and lilac. Creamy mouthfeel. Just-so-slightly bitter finish with an orange-rind presence.

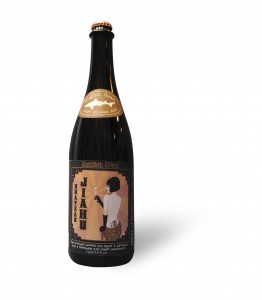

“Midas Touch,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from 2,700-year-old drinking vessels recovered from the Turkish tomb possibly belonging to the person (or a relative) mythologized as King Midas. Brewed from barley malt, honey, white muscat grapes and saffron. 9% ABV.

“Midas Touch,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from 2,700-year-old drinking vessels recovered from the Turkish tomb possibly belonging to the person (or a relative) mythologized as King Midas. Brewed from barley malt, honey, white muscat grapes and saffron. 9% ABV.

A lemony-citrus nose, with mild notes of saffron. Malt and more citrus on the palate, and a bit of toast. Crisp and beer-like.

“Theobroma,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from Honduran pottery residue circa 1200 BC. Brewed from cacao powder and nibs, honey, Ancho chiles, and achiote (annatto). 9% ABV.

“Theobroma,” Dogfish Head, Milton, DE. Recreated from Honduran pottery residue circa 1200 BC. Brewed from cacao powder and nibs, honey, Ancho chiles, and achiote (annatto). 9% ABV.

Completely chocolatey on the nose, but no chocolate present on the palate. Quickly moves to a “spice soup” and malted flavor. Chile notes seem to appear and disappear between sips. Changes with every taste. Wild, unexpected, and difficult to analyze in the sample size poured.

Recommended reading: For a greatly detailed journey into the history and science of life, culture and alcoholic beverages, see Dr. Patrick E. McGovern’s book “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer and Other Alcoholic Beverages,” University of California Press, 2009.

Dogfish Head plans a Fall release of their latest collaboration with Dr. Patrick E. McGovern—Ta Henket, an ancient Egyptian brew identified through hieroglyphics and recreated with dom-palm fruit, za’atar, chamomile, and wild yeast isolated from a date farm in Cairo.

Emily Towe lives, writes and makes wine in San Diego, where she blogs about her family’s garagiste adventures at jbrix.com. Heading into her third winemaking harvest in 2011 along with her husband, Jody, Emily is always pleased to share a glass with friends new and old in the j.brix garage micro-winery. Follow her on Twitter at @emilyldt.