Each week until the end of the year we’ll take a look at different types of sparkling wines – Champagne included, of course – so you’ll be able to make a great choice for your New Year’s Eve occasion.

Rather than an exhaustive explanation of champagnes and sparkling wines, this series is meant to provide an overview along with some food-pairing tips. We’ll give specific examples, both classic and new. Read the descriptions and you’ll be able to find something similar if your wine shop doesn’t have any of the brands mentioned here.

South Africa shows up

Living in the US, we tend to drink sparkling wine either from this country or from Europe, so I was pleased to see some wines from as far away as South Africa here this season. South Africa’s Méthode Cap Classique sparklers are crafted in the traditional (champagne) method. I sampled Krone sparkling wines, made with the traditional grapes chardonnay and pinot noir, and they are so “traditional” they are fermented in the bottle and hand-riddled in wooden racks. The grapes are picked at night and in the early morning, while the vineyards are still cool. The 2012 Krone Borealis Vintage Cuvée Brut is a tawny gold, with very light aromas, strawberry and peach on the palate and quite reasonable acidity. The 2012 Krone Vintage Rosé Cuvée Brut is a lovely color and even drier, with more perceptible acidity. These wines are just entering the US market (under $20).

More from France

Maybe you’re looking for fizz that’s easier to find? Knowing that Champagne is the sparkling wine made in the Champagne region of France, you might wonder about other regions of France: do they make sparkling wines? If so, what are they called?

Maybe you’re looking for fizz that’s easier to find? Knowing that Champagne is the sparkling wine made in the Champagne region of France, you might wonder about other regions of France: do they make sparkling wines? If so, what are they called?

Not too long ago, French sparkling wines became more standardized, in name as well as production and style. Those made in regions outside of Champagne are generally referred to as “crémant.” It’s a term I like because to an English-speaker, it infers creaminess or foaminess: generally appealing qualities in a sparkling wine.

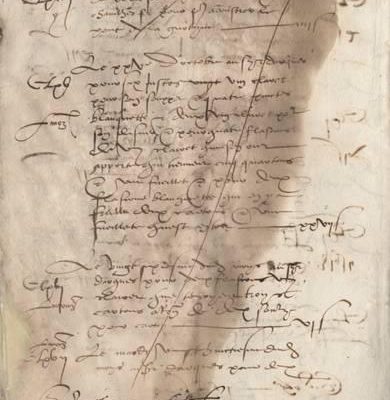

Crémant is made in many regions, from Burgundy to the Jura, and as far south as Limoux, in the Languedoc-Roussillon area. Limoux is especially important because there is evidence of trade in sparkling wines here as early as the mid-16th century (in a document I plan to look at, next time I’m in the area). So Limoux has a modern Crémant de Limoux (made with more chardonnay and chenin blanc than the indigenous mauzac grape) as well as a Blanquette de Limoux (mauzac), which references its 400 year history.

Closest to Champagne we find Burgundy and Alsace. Both are northern regions in terms of the types of grapes they grow and in the styles of sparkling wine they make. They mainly use the same grapes as Champagne – chardonnay and pinot noir – which are also native to Burgundy and Alsace (though Alsace also uses the white grape pinot blanc). Burgundian producers imported Champagne’s know-how over 150 years ago. Alsace made a small amount of sparkling wine from the late 19th century through the middle of the 20th century, when production began to increase. Both regions make brut sparkling wines in the traditional method. There are many excellent Crémant d’Alsace wines. And, many Burgundy’s créants have improved in the past decade as demand for sparkling wine has increased worldwide. More and more sparkling wines from Burgundy and Alsace are available in the US today at lower prices than champagne.

US Goes Gold

Going in a completely different direction, you might be tempted to try some of the random sparklers that seem to appear out of nowhere this time of year. Caution: price does make a difference here.

Going in a completely different direction, you might be tempted to try some of the random sparklers that seem to appear out of nowhere this time of year. Caution: price does make a difference here.

Also you might be hobbled by the opinions of your friends and acquaintances. Some insist they only like French champagne, while others maintain they can only drink the driest sparkling wines. I take it all with a grain of salt because I’ve been experimenting with blind tasting for years, and I now often don’t tell people what they are drinking. I just ask them to taste several sparklers and choose the one they like best for the rest of the evening.

Recently, I got some XXIV Karat sparkling wine with flecks of real 24-karat gold swirling around in the bottles, which I thought would be fun for New Year’s Eve ($33-$37). Both tasted sweet and fruity to me, but the bottles with their gold flecks were festive so I took them along to a party.

I found the “Rosé” had strong notes of cassis, like a Kir Royale in the bottle – and this kind of threw people for a loop when they sampled it without expecting the fruitiness. When I tasted the “Brut” I was underwhelmed because I felt the florals and fruits conflicted with attempts to make the wine more toasty and yeasty like champagne. But it did improve with food, and that’s what people chose to drink with their appetizers. The grapes are from Mendocino, the wine was made in the charmat process and it was bottled in Lodi. But the people who tried it were happy with their choice – and luckily forgot to question me about the wines at the end of the evening. Don’t ask, don’t tell…