Norton is the state grape of Missouri, which may sound a little odd for a grape that was first cultivated by Dr. Daniel Norborne Norton of Richmond, Va., in the 1820s. Just short of its 200th birthday, the dark, small berry produces some of the best red wine made in the United States. A dry, rich, deeply hued red, it is probably best compared to a Syrah, and it is also responsible for some excellent, well-aged port-style wines as well.

Not only good, but good for you, as the ads used to say. The grape has high concentrations of resveratrol, an excellent anti-oxidant. For an indigenous American grape, norton has some strange characteristics. It’s neither a labrusca (concord, scuppernong), nor a vinifera (cabernet sauvignon, merlot), but a Vitis aestivalis. That means it does not have the “foxy” flavor that so many of its American relatives display.

Norton has been grown commercially since at least 1830, and its wine has been produced in Hermann, Mo., and at various Virginia sites ever since. In 1873, a Norton from Hermann won a world championship at an international wine fair held in Vienna. Unfortunately, no one remembers the vintage date. The vines, which are resistant to phylloxera and other diseases, might have been among those shipped to California, and to France, in the 1870s, where they helped re-establish the grape industry.

The Missouri wine industry, practically obliterated by Prohibition, started a comeback around the middle of the last century, and the Nortons produced at Stone Hill, Mount Pleasant, St. James, and other pioneer wineries helped lead the way for an industry that has grown to more than 100 wineries across the state.

At the same time, Virginia wineries took an interest in the grape that often went by the names of Virginia seedling and cynthiana. Dennis Horton began making it in his winery near Charlottesville, and had the advantage of rhyme when he talked of Horton’s Norton. Another Virginia winery, Chrysalis, has some major plantings, and the grape is grown in Texas, too.

I’ve tasted the Horton version; it displays excellent fruit but it seems a touch lighter than the Missouri version. It might have been a difference because of a vintage variation, or because of a winemaker’s decision.

Stone Hill Winery (Hermann, Mo.) specializes in Norton, and Dave Johnson, the winemaker since 1978, probably has tasted more Norton than almost anyone. He is also an MC at an annual Stone Hill springtime event, a public tasting of ten years of Nortons, wines made from the grapes picked a half-year earlier to those with considerable age. The date also marks the release of the newest Norton to go on sale. In the most recent, we tasted the 2001 through 2010 wines, including a barrel sample of 2009 and the newly released 2008. The winery has been doing this more than 20 years and I have taken part in almost all of them. I think it is a rather courageous move, offering wines that have been aged in the winery’s cellar rather than expecting consumers to do their own aging.

So just how long should a Norton age? How long can it age?

Talking to three experienced winemakers with lots of time around the barrel, it was a little surprising to hear such unanimity.

Tony Kooyumjian, owner-winemaker at Augusta and Montelle wineries in Augusta, Mo., is a former airline pilot who has won many awards with his wines, and Hank Johnson, owner of Chaumette Winery in Ste. Genevieve, Mo., along with Dave Johnson, shared their thoughts, but were surprisingly unanimous in their thinking. The Johnsons, by the way, are not related.

All three agreed that about 15 years, even under optimum conditions, is about as far as one can go in finding Nortons that still are enjoyable, and while Tony noted he has drunk some twenty year old Nortons that were excellent, he added. “They’re an exception.” They also pointed out that a general change in winemaking style with Norton over the last 10-15 years has given them longer lives. A lower pH, they agree, has given them more stability.

And all thought that well made Nortons improved slowly in bottle for the first five years, then jumped ahead and reached their peak in the next three or four. Hank suggested that a little less tannin benefited some of the Nortons.

I have been drinking Nortons for a long time, too, and I am very fond of the wines. With some good ones, I have blown away wine snobs who decried the grape’s ability to make world class wines. But all the expert commentary, from me, from winery owners, from winemakers, from connoisseurs, is well-meaning speculation, perhaps improved by the sheer numbers of Nortons we have tasted. All vintages are different, all terroir is different, all storage conditions are different, and all palates differ.

I think we can agree, however, on the fact that Norton can be a great red wine, needs 8-10 years of bottle age to reach its peak, holds that level for 4-5 more years, then loses it.

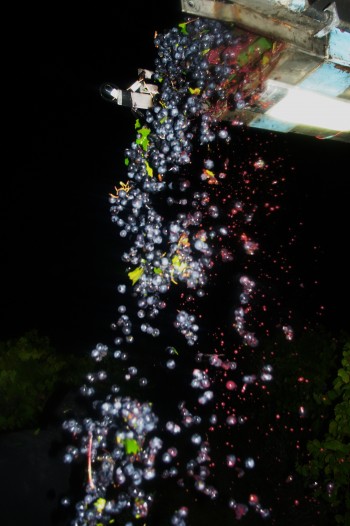

Photos for this article provided by the Missouri Wine and Grape Board.

Joe Pollack has been writing and talking about sports, wine, food, entertainment and other happy subjects for more than 50 years for newspapers, radio and TV stations, magazines, newsletters, blogs and other means of disseminating words and opinions. He has children and grandchildren scattered throughout the world and a wife, Ann Lemons, who is a good writer and an even better cook. He writes at St Louis Eats.