Picture a public tasting, an important one, held in Montpellier, France. People are tasting American wines. And grimacing.

The wines are too sweet. Too primitive. And too funky.

People want to like them, really they do, but these American wines just don’t seem good enough to save the wine world, and the wine world needs saving.

This tasting was held in 1874, as phylloxera marched across Europe, and French people confronted the possibility of a future in which American wine was all there would be to drink. The US, which had given the world phylloxera, also offered salvation with its native grapevines.

Now, 140 years later, the US once again offers salvation for the wine world.

The consumer first

This time, it’s with something else entirely: knowledgeable, enthusiastic consumers.

Not that US wines are shabby. UK critic Jancis Robinson rated US red wines, on average, as second-best in the world over the last 13 years, behind only Portugal. (Method: She simply averaged every wine that she rated from each country.) That’s a little surprising at first, but makes sense when you think deeply: how often do you have a flawed wine from the US? We are now the source of grins, not grimaces.

But it’s not our sophisticated and subtle winemakers who will save the wine world. It’s our ordinary consumers, also more sophisticated and subtle than they get credit for. And generous, and as far from homogeneous as wine consumers get.

It’s that last point that matters.

That the US is now the world’s largest wine market is not news. Some of that is simply that we have a bigger population than any European country. Amazing to Europeans, 1/3 of American adults report not drinking alcohol of any kind.

But the wine drinkers we do have are special, unlike any in continental Europe.

We’ll try wines from anywhere, and we’ll pay for excellence and uniqueness. You hear this story over and over from European producers. Joep Bakx makes a wine in the unacclaimed Bordeaux Supérieur region that he sells for $32 in the US. He puts extra effort into working his vineyard, and it shows in the wine. But he couldn’t sell a Bordeaux Supérieur for 23 Euros in Europe. He could, however, sell it to sommeliers and wine buyers in New York.

Where do producers of fine wines in Portugal, Turkey, Israel, Uruguay most want to sell their products? The US, because we’ll pay fairly and our thirst is always growing.

The domestic threat

I’m feeling a bit boastful about this because France, Italy and Spain — the bulwark of European wine producers, and the source of some continental superiority a generation ago — they need us.

I’m feeling a bit boastful about this because France, Italy and Spain — the bulwark of European wine producers, and the source of some continental superiority a generation ago — they need us.

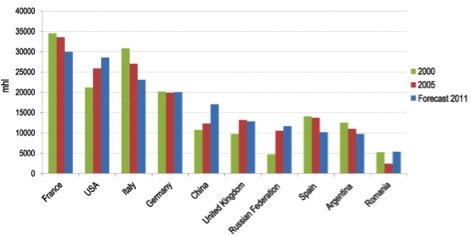

Wine consumption is plummeting in these countries: down 20% from 2000 to 2011 in France, 30% in Italy, and nearly 40% in Spain.

Not long ago, young beer-drinking Americans would grab a backpack and go to Europe, where their counterparts would introduce them to wine. That world has turned upside down. Now recent American college graduates buy a Eurailpass so they can visit vineyards where their favorite wines come from, while young continental Europeans turn up their noses at the tipple of their grandparents.

You don’t see Italians signing up for Italian wine appreciation courses, unlike people all over the US. Try asking a young Spaniard about which other countries produce Garnacha.

Americans used to think Europeans were sophisticated about wine. But wine culture in Europe is deteriorating like a religion people no longer believe in, and it’s hard to say what if anything will reinvigorate it. Maybe France needs to create its own “Sideways.” There are plenty of wine-based movies coming out of the continent, but none of them have struck a cultural nerve, maybe because that nerve has atrophied.

The decline of the European domestic wine market is the most serious crisis for the European wine industry since phylloxera. Even two world wars fought in the vineyards didn’t present such a long-term threat.

Parts of France are sanguine about this. The top Bordeaux chateaux are selling most of their product to China, and the Chinese have discovered Burgundy. The Champenois can be happy that Russia’s economy is improving and that wine consumption is up 25% in the UK. But the rest of Europe, they need us.

Switching gears

The story of the next 20 years of European wine is the story of switching from domestic focus to exports — and to exporting here.

The story of the next 20 years of European wine is the story of switching from domestic focus to exports — and to exporting here.

Wineries that succeed will have good English websites. Astute European winegrowing families will send their kids to the US to study the language so they can represent their wines.

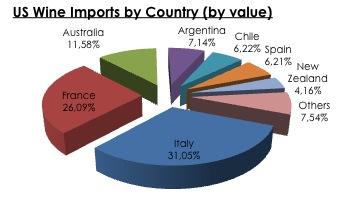

There’s never been a more difficult time to compete for the bulk $10 wine market in the US. Successful European wineries will realize that it’s better to make fewer, somewhat higher-priced, more profitable wines. It’s easier to carve out a niche for an artisanal product — single-vineyard wines of character, maybe in the $25 range — than to fight Australia and Chile and Argentina on the supermarket shelves.

And successful wineries will come here, all the time. Maybe they’ll station a family member here, or create an outpost, like the Drouhins in Oregon and the Perrins in Paso Robles. Not only will they have a local product; having people on the ground here will help them understand the market.

It has been 150 years since America imperiled European wine by introducing phylloxera. Our time has come to truly make amends, and we will do it in the most delicious way possible, by buying Europe’s best wines, studying them, swapping them, drinking them, honoring them. Lafayette, we are here, and we come bearing wine glasses.