Me: “This one is a little gamey.”

He: “That’s a white Burg for you.”

Me: “I dunno. I think it might be Brett…”

He: “In a white? No. It’s just, French.”

Me: “You sure? Smells like Brett to me. <pause> How about I get it tested?”

He: “Sure. I’d be shocked if it had Brett. Have this ’04 Rayas done as well while you’re at it. It’s filthy for sure.”

The above is an actual conversation I had with a talented and respected maker of wine. I had another, eerily similar conversation with a wine educator soon after when tasting yet another white Burgundy I suspected of the B-funk.

Both cases are interesting. Not because I want to argue that I possess some superior ability to detect Brettanomyces—a particular yeast that can produce wet horse, barnyard and other (more pleasant) leathery-earth smells in wines. You’ll soon see that just isn’t the case.

Instead, I think it’s worth discussing because both of these experienced wine tasters simply didn’t think it possible for Brett to survive in white wines. It goes against conventional wisdom. And yet I won my bets in both cases.

Choosing My Battles

In French wines especially, notes of barnyard and earth are often attributed to terroir and held up as models of “transparent” winemaking. In other words, it is the old saw that if producers would just get out of the way, more of the vital and defining characteristics of a vineyard and vintage will show through in a wine.

Now, you won’t get any argument from me that minimal input winemaking produces a more interesting wine. But a lot of what passes for nuance and terroir in old world wines smells, to me at least, suspiciously like the same spoilage organisms we have over here in the new world combined in exotic and sometimes captivating ways. But I’m not interested in a terroir holy war.

What I am interested in is this: how in the world are the French able to grow so much Brett in their whites?

It’s a tough nut to crack, and there is no single answer.

For instance, there is a sort of consensus the world over that Brett comes from both barrels and from the vineyard. New barrels seem to be a common culprit. Once Brett sets up house in a barrel it is pretty much there to stay, though populations can be managed through rigorous cleaning and use of sulfur dioxide (SO2). SO2, the preservative almost universally used in wine, in modest amounts can cause Brett yeast to go into a kind of hibernation.

Many French producers do indeed use a lot of new oak, and so there may perhaps be a link there. But we use a lot of new French oak over in the States as well, often from the exact same coopers, and I haven’t noticed the same smells in American Chardonnays with anywhere near the frequency that I do in white Burgs.

Brett is also sensitive to pH, or the acidity in wine. The higher the acid, the less hospitable the wine is for Brett. Typically a white Burgundy will have a much lower pH (higher acid) than its American cousins. Moreover, at lower pH (higher acid), SO2 is much more effective. All of which would argue for white Burgundy to be very resistant to Brett.

Welcome to Geeksville

Population: Me

So, as you can see, there are legitimate reasons why experienced wine tasters would not suspect white Burgundy to be a hotbed of B-funk activity.

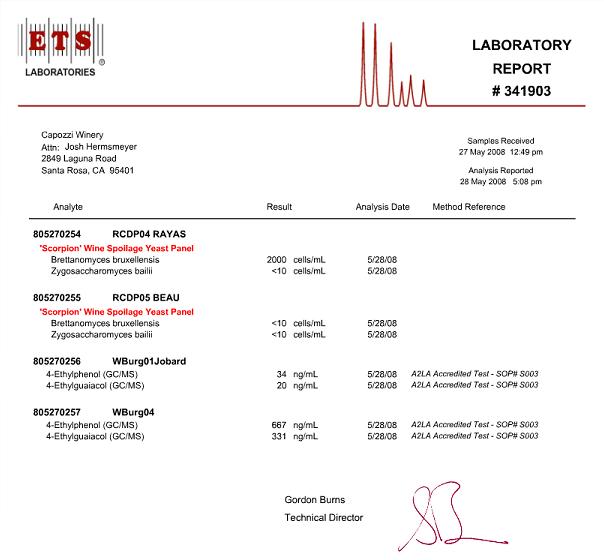

And yet here we are. Below is the ETS lab report for four wines tested for Brett in various ways. The first two results are Rhone reds, an ’04 Rayas and an ’05 Beaucastel. They were tested for the presence of the yeast itself using genetic detection methods; the other two, white Burgs, were tested for the compounds produced by the yeast. Those compounds, 4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol contribute different smells to a wine depending on their concentration and the ratio between the two of them.

Sensory thresholds, or when we can actually start smelling the results of the Brett yeast, depend a lot on the nose doing the sniffing. ETS Labs argues for 300 ng/ml for 4-EP and 50 ng/ml for 4-EG, but your mileage will certainly vary. Another fun fact from ETS Labs: the ratio between the two compounds is typically between 3:1 and 10:1, with the majority of the aroma coming from 4-EP.

As you can see, both white Burgs showed evidence of Brett. The second of the two, a Domain Michel Niellon 1er Cru, had a whole lot, and a ratio of 2:1 4-EP to 4-EG! The ’01 Jobard had just a little of both of the smellies.

Moral of the story? If you think you smell Brett in your glass—even if it’s white, and especially if it’s French—you might just be right. And certainly don’t let anyone tell you it’s impossible.

What of the two reds, the Rayas and the Beaucastel? It’s funny… I was sure the Beaucastel had Brett, probably for the very reason that the other winemaker thought the white Burg didn’t. Beaucastel has had a history of Brett in their wines, so I was just as guilty of pre-judging as anyone. In the end it was absolutely pristine (and delicious). I was imagining things.

And the Rayas? Well, no one got that one wrong. It was filthy.

– Josh Hermsmeyer, of Capozzi Winery, is a recognized expert on social media marketing for wineries. Trained at UC Davis in both economics and winemaking, he blogs at PinotBlogger.