Visiting a wine region is a living lesson in the story of a wine. It provides context: a geographic and historical tapestry that illustrates the wine’s individual narrative. The majestic backdrop of Alto Adige, stunningly nestled between imposing mountains and vibrant greenery as far as the eye can see, certainly provides that element. But as a recent trip showed, an even deeper story can emerge from underground cellars such as those at Kellerei Terlan, where I recently had the chance to discover a genealogy of white wines more than a half-century old.

As part of the 2011 European Wine Bloggers Conference, select (and I might add fortunate) participants travelled to the northernmost part of Italy, just southwest of the Austrian border. Situated in the Alps, Alto Adige has a mixture of limestone and volcanic soil that imparts a striking minerality to the wines. The region, one of the oldest wine-growing areas in Italy, boasts a viticultural heritage dating back to pre-Roman times.

Centrally located in the region between Meran and Bozen, the land around Terlan is both a benefit to the wine style but a challenge to the vignerons. Due to steep slopes, maintaining the vines, some of which are nearly eighty years old, and hand-harvesting grapes can take twice as much time as similar work in the valley.

At Terlan, 172 hectares are dedicated to winemaking and planted at elevations ranging from 250 to 900 meters above sea level. Roughly 65% of that land, mostly on rocky terraces, is dedicated to white wine varieties. Intensely sunny days starkly contrast with cool evening temperatures and create a microclimate particularly well-suited for white wines like Pinot Bianco. Structured as a cooperative, Terlan’s ability to leverage multiple growing sites has contributed, according to the winery, to its ability to develop its complex white wines and apply innovative, perhaps even non-traditional, winemaking techniques.

At Terlan, 172 hectares are dedicated to winemaking and planted at elevations ranging from 250 to 900 meters above sea level. Roughly 65% of that land, mostly on rocky terraces, is dedicated to white wine varieties. Intensely sunny days starkly contrast with cool evening temperatures and create a microclimate particularly well-suited for white wines like Pinot Bianco. Structured as a cooperative, Terlan’s ability to leverage multiple growing sites has contributed, according to the winery, to its ability to develop its complex white wines and apply innovative, perhaps even non-traditional, winemaking techniques.

The ruins of Neuhaus Castle can be seen from the winery and are depicted in a stylized design on the labels of the classic Terlan wines. Looking up the steep hills at the neatly terraced vineyards, I was overcome by the sense that if I had visited fifty years earlier, the landscape would have looked much the same.

The winery’s structure itself is more modern but still draws inspiration from nature’s prowess. Large oxidized iron doors guard the cask room. In a revelatory position at the end of a long, dark hallway, a narrow swath of earth is exposed, showing the terrain’s stony composition and the stubborn persistence that the vines must possess to succeed.

The wines happily reflected their environs. As expected from higher altitudes and cooler evening temperatures, the Pinot Bianco wines were dry, full-bodied, and possess an acid backbone that provides the necessary structure to evolve. What affected me the most was how unique and individual each wine was, reflecting not just the common sense of place but an integrity of the vintage.

The wines happily reflected their environs. As expected from higher altitudes and cooler evening temperatures, the Pinot Bianco wines were dry, full-bodied, and possess an acid backbone that provides the necessary structure to evolve. What affected me the most was how unique and individual each wine was, reflecting not just the common sense of place but an integrity of the vintage.

Impressively, the modest-sized winery maintains a cellar of more than 400,000 to 500,000 bottles. It also houses a wine archive of more than 20,000 bottles comprising significant vertical collections from 1954 to present, as well as select vintages dating back to 1893, the year of the winery’s founding. When you factor in that we’re talking about white wines, rather than the more obviously age-worthy reds, it gets even more interesting. A tasting of seven Pinot Bianco vintages was full of pleasant surprises and a lesson in the incredible aging potential of certain white wines.

Fifty years in seven wines

We began our session with the current vintage. Fermented in stainless steel, then aged on fine yeast for six months, the Terlan Pinot Bianco from 2010 was exactly as expected. Like a young, crisp, highly acidic apple, the wine also exhibited the vibrant character of a young filly eager to break out of the racing gate. In 2010, one of the lowest yielding vintages in the last 20 years, the grapes maintained a ripeness and fullness of flavor with a baseline of minerality. The wine retails for between $15 and $20 a bottle in the United States and, based on my experience, is a stellar representation of Pinot Biancos from the region.

We began our session with the current vintage. Fermented in stainless steel, then aged on fine yeast for six months, the Terlan Pinot Bianco from 2010 was exactly as expected. Like a young, crisp, highly acidic apple, the wine also exhibited the vibrant character of a young filly eager to break out of the racing gate. In 2010, one of the lowest yielding vintages in the last 20 years, the grapes maintained a ripeness and fullness of flavor with a baseline of minerality. The wine retails for between $15 and $20 a bottle in the United States and, based on my experience, is a stellar representation of Pinot Biancos from the region.

Four of the seven wines tasted were from a special vineyard, the Vorberg, with sun-facing southern slopes that are rich in deep red volcanic rock. The Vorberg wines are fermented in large oak casks, then put through malolactic fermentation and aging on fine yeast for 12 months, leading to a generally more medium-bodied, supple mouth-feel.

The 2009 Vorberg Terlano Pinot Bianco Riserva, a medium-yield vintage, imparted a delicate aroma of panna cotta with fresh mango. Despite its acidity, its creamy mouth-feel created a lovely and unexpected contradiction.

The next three wines were delivered in magnum formats—a festive event in and of itself.

Both the 2006 and the 2004 had much stronger fungal, vegetal aromas (the 2004 more markedly so, particularly on the palate). It was hard to tell if this was characteristic of the vintages or indicative of the ageing cycle of the variety. Both exhibited Terlan’s characteristic well-balanced acidity.

The 2006 Vorberg Terlano Pinot Bianco Riserva initially imparted a slight chalky nose reminiscent of the dust that billows off elementary school chalkboard erasers. With the 2004 Vorberg Terlano Pinot Bianco Riserva magnum, the roasted mushroom flavors were significantly more prominent and didn’t really dissipate over the next hour or so.

In the 1999 Vorberg Terlano Pinot Bianco, the last sampled from a magnum bottle, we were treated to a perhaps more expected aromatic character. Redolent of canned pineapple and macerated apricots, the 1999 had a soft, supple mouth-feel that began to demonstrate the benefits of aging Pinot Bianco. Winery representatives speculated that this would age for yet another 20-30 years.

Aromatically, the 1987 Terlano Pinot Bianco was a ringer for marmalade on toast. The richness of baked bread and candied orange peel were mirrored on the palate, with the addition of a slight smokiness. From a vintage perspective, we were told growing conditions, yields and wine style were repeated in 1999, so the 1987 should provide some indication as to how the 1999 might age.

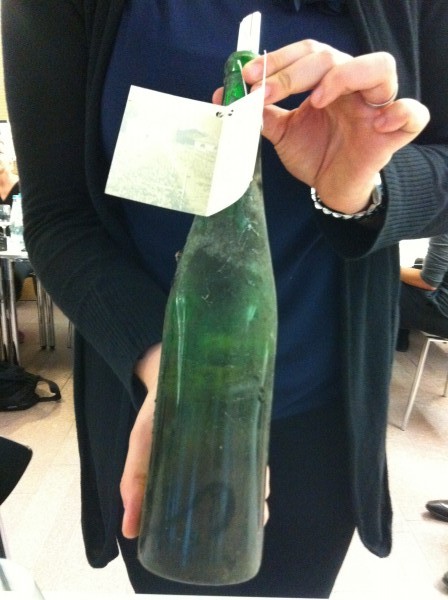

And now, for the Grande Dame: the 1959 Terlan Pinot Bianco. Swirling the rich straw liquid in the glass released smells of candied mangoes, butterscotch, and a pleasant earthiness. Like a sherry, it was oxidative on the palate, but not unpleasantly so. Layered and complex with a strong finish, it was certainly the oldest wine I’ve tasted, and the bottle was so historic that (we were told) the label had peeled off at some point in its lifespan. As our gracious host twisted the bottle for my iPhone snapshot, clumps of dust floated to the table as a reminder of the decades that this wine remained undisturbed in the winery’s cellar (it left a mere 220 comrades from the same vintage behind).

Let’s just pause a moment here to reflect: when these grapes were developing on the vine, women couldn’t yet vote in Switzerland, Hawaii had just become a state, and Castro was the newly-anointed leader of Cuba. It was a long time ago, and despite all efforts at impartiality, that sense of history, of a past that existed long before most people in the room were born, fueled reverence on my palate.

In the short while since I have been back in the States, I sampled a very different Pinot Bianco—or rather, Pinot Blanc—from Alsace. While that does not constitute an empirical study, it still provided a striking contrast to the wines that I tasted at Terlan and other wineries in Alto Adige. At the same price point, it was, simply put, fine. It lacked the aromatic richness that the Terlan wines exhibited, the finesse with refreshing, long-lasting layers, and persistent flavors on the palate. And because of my experiences in Alto Adige, because of the background proffered by dramatic geography, I could recognize and explain some of the olfactory differences I detected. Coupled with the opportunity to tunnel a layer deeper into the archives of a grape variety, ever so briefly, to witness the evolution of Pinot Bianco’s intrinsic character with a remarkable vibrancy and life—I daresay it significantly improved my personal view of Pinot Biancos as a whole. A happy day, indeed.

I owe a special thanks to my tasting companion at Terlan, Angela Kallsen of The Wine Company in Minnesota, whose perceptive and unique tasting observations helped me to improve upon my own.

Katie can’t pinpoint the moment at which she fell in love with wine—she just has, for as long as she can remember. Fortunately she found a way to professionally integrate her passions for wine, food, and travel with her overactive social tendencies and hasn’t looked back since. After getting dual degrees in art history and international studies at SMU, Katie pursued a career in marketing communications, working with a number of business-to-business and consumer clients while at The Richards Group based in Dallas. She now works for Zebulon, North Carolina-based Nomacorc. She lived in Texas the longest, followed by Paris, France, then New York City, which she currently calls home. Katie can be found on Twitter at @KatieDrinksWine or perusing the streets of Manhattan in search of interesting food and wine adventures.

Katie can’t pinpoint the moment at which she fell in love with wine—she just has, for as long as she can remember. Fortunately she found a way to professionally integrate her passions for wine, food, and travel with her overactive social tendencies and hasn’t looked back since. After getting dual degrees in art history and international studies at SMU, Katie pursued a career in marketing communications, working with a number of business-to-business and consumer clients while at The Richards Group based in Dallas. She now works for Zebulon, North Carolina-based Nomacorc. She lived in Texas the longest, followed by Paris, France, then New York City, which she currently calls home. Katie can be found on Twitter at @KatieDrinksWine or perusing the streets of Manhattan in search of interesting food and wine adventures.