Compromise is in the air these days. The rockets have quieted in the Middle East. Republicans are talking about taxes while Democrats entertain cuts in entitlement spending.  President Obama is having lunch with Mitt Romney. Even Mark Sanchez, in an act of selfless immolation, decided to distract New Yorkers from the sting of a failed Yankees postseason by shifting their attention to his hapless football exploits.

President Obama is having lunch with Mitt Romney. Even Mark Sanchez, in an act of selfless immolation, decided to distract New Yorkers from the sting of a failed Yankees postseason by shifting their attention to his hapless football exploits.

Surely the war over wine’s 100-point scale pales in comparison to these weighty matters. We can find a compromise for wine, right? One with impeccable balance and a finish that lasts forever?

In fact, we can. When it comes to the 100-point scale, there are two deeply entrenched sides. Those who loathe the scale say it’s an egregious error in the understanding of wine and either you’re with us or, well, you’re with the errorists. Those who defend the scale point to its ease of use and, in the advent of Cellartracker, its democratic appeal.

But I propose a compromise that should begin to satisfy both parties. It’s a compromise that recognizes the utility of the scale; after all, a consistent taster can help readers who come to know his or her preferences. And it’s a compromise that recognizes wine is not just a number, and by reducing everything to points, we are prone to missing the very reason why so many of us drink wine.

Here is is: Keep the 100-point scale, but ditch it for wines 25 years old or more. I’ll explain why in a moment.

The War on Notes

The tasting note is under assault of late, with the most blistering incident coming from the deliciously poisonous pen of Bill Klapp. On the discussion forum at Wine Berserkers, Klapp takes apart a truly awful tasting note written by Neal Martin of Wine Advocate. (It’s worth reading Klapp’s entire takedown; click here.) And as Dr. Vino points out, New York Times’ writer Eric Asimov lashes the tasting note in his recent book (which was reviewed on Palate Press; click here).

The tasting note is under assault of late, with the most blistering incident coming from the deliciously poisonous pen of Bill Klapp. On the discussion forum at Wine Berserkers, Klapp takes apart a truly awful tasting note written by Neal Martin of Wine Advocate. (It’s worth reading Klapp’s entire takedown; click here.) And as Dr. Vino points out, New York Times’ writer Eric Asimov lashes the tasting note in his recent book (which was reviewed on Palate Press; click here).

The most important point Klapp makes is about the simple lack of good writing in most tasting notes. Some notes are obvious attempts to sound erudite; others suffer from hyperbole; many others (such as the note Klapp flayed on Wine Berserkers) make a mockery of the English language. At the end of these notes, we’re supposed to trust a score?

What Klapp does not say is that some critics write effective tasting notes that zero in on precise aromas and flavors — or as precise as one’s impression can be — without the stain of hyperbole or tortured word choice. Some scores reflect rigor and consistency.

The anti-score crowd points out that wine consumers don’t drink wine in a lab with brown bags in an assembly-line format. Why, they ask, should wines be scored in a way that is contrary to how the consumer will experience them? They’re right, but they’re wrong. I’d rather not score wines at all, but if they’re going to be scored, then removing bias is a noble goal. Just because consumers don’t do it that way doesn’t mean the critics shouldn’t either.

Drawing the line

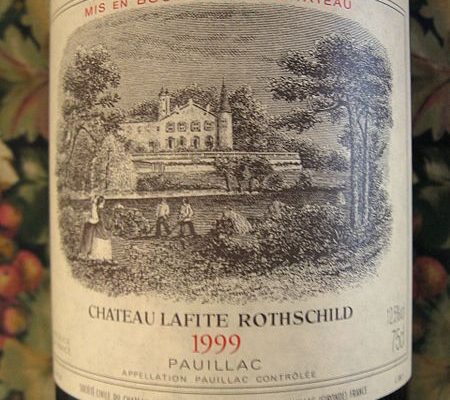

Here’s where we can draw the line: Wines older than 25 years should not be scored. Pinning a score on a wine from, say, 1945 misses the point of what you’re drinking. We seem to be bordering on an obsession with scores when we can no longer simply enjoy a wine that is 165 years old without putting a mathematical marker on it. Here’s the note posted on Wine Berserkers recently for a bottle of 1899 Lafite:

Surprisingly, this was still kicking and extremely pleasant. On the nose, some red fruits, currants, leather, cedar, aged meats, dried tobacco, earth, coriander, dried tea leaves, and also some greenness in the form of dried cilantro, grass clippings, and a hint of mint leaves. On the palate, again still very much alive and showing great depth; red fruits, tea, dried herbs, tobacco, earth and a hint of mint, which frame the long, persistent finish. Acid is present, but not taking over, refreshing. (96 PTS)

I can think of nothing more pointless than giving a score to a bottle of 1899 Lafite. What meaning does it have? A score is supposed to measure a wine’s overall quality, or it is supposed to measure the wine’s quality against its peers. There are no peers for an 1899 first growth that is still wondrously alive. If we’re fortunate to come across one bottle in our lifetime, it is a moment to appreciate, not to calculate. Offering a score seems to indicate a writer’s insecurity in their ability to convey just how special this wine was. The tasting note is clear enough; a score is obscene in this context.

Yes, 25 years is an arbitrary number. Any time you draw a line in this way, there’s going to be an arbitrary component. The perfect cannot be the enemy of the good. But we’ll make some exceptions. Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Barolo will be set aside because those wines can remain fresh and vibrant even at several decades in the bottle. I’ve had Baroli from the 1960s that smelled youthful. More relevantly, many of those wines are made to be consumed after many years. No doubt winemaking in these regions has changed to favor wines more accessible in their youth, but that doesn’t remove the potential of these wines to evolve for many more years than most wines. So go ahead, slap a score on a 1964 Barolo if you must. For Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Barolo, we’ll allow scores going back 50 years.

What Is It Saying?

But please, make the score an aside, not the core of your commentary. If I can wait until 2035, I’ll be able to open a 2004 Giuseppe Mascarello Monprivato that speaks to a time and place with meaning to me. I’ve been on those Piedmont soils. I remember that year. Who knows what the world will be like when that wine is more than three decades old? Whatever the answer, the wine will awaken a memory of a time I can vividly recall. I doubt I’ll want to score the wine. I’ll be much more concerned with contemplating it — and what it’s saying. It will not be saying, “94 points,” I’m rather certain.

Supporters of the scale might see this as the first step in a slippery slope toward scorelessness. It’s not. The score is so entrenched that it could hardly be eliminated with a daisy cutter explosion. I’ve stayed away from scoring wines for the most part; I appreciate a solid reviewer’s consistency, but I prefer the story to the points. I worry that tasting notes make us vulnerable to celebrating hedonism and hyperbole over subtlety and the expression of place. But I can’t fully agree with Klapp and his ilk, because a good tasting note is helpful, educational, and occasionally even inspiring.

So this is the middle ground. Let’s agree to leave the scale alone as long as we don’t fetishize points so much that we lose the meaning of an aged bottle. We can co-exist with the 100-point scale as long as it doesn’t cheapen the special occasions when we can reconnect with the past through a well-preserved bottle. We can compromise in the wine world, we can refrain from scoring old wines, we can live with numbers on most wines, and we can all, in fact, just get along.