What is it that fascinates us so much about Georgia? Interest in this small nation nestling under the Caucasus mountains seems to be at an all-time high – in the last month alone, a clutch of three major books on the nation’s food and wine hit the shelves. And there are more in the pipeline.

Perhaps it’s the location: Irresistibly situated at a crossroads of East and West, Georgia feels exotic, but has just enough Western influence to lend a sense of familiarity, to provide a frame of reference for Western visitors. Perhaps it’s the uniqueness of the culture, the wine and the language. As the republic finds its feet after a messy first two decades of independence, these traditions are increasingly being revived and celebrated as the precious jewels that they so clearly are.

Then there’s the “cradle of wine” assertion – that Georgia can trace a history of vine-growing further back than almost anywhere else. The famous grape pips found on a qvevri fragment in the East of the country were carbon dated to approximately 6,000 BC (I say this with caution, as neighbouring Armenia currently boasts the oldest archaeological remains of a winery).

All of this adds up to a very potent mix of culture, history and living traditions such as the supra (feast), the toastmaster (tamada), polyphonic singing and of course the qvevri (amphora-like vessel for fermenting ageing wine). It isn’t surprising that Georgia is becoming an important tourist destination, especially for wine lovers who want to get to grips with one of the world’s oldest and most integrated wine cultures.

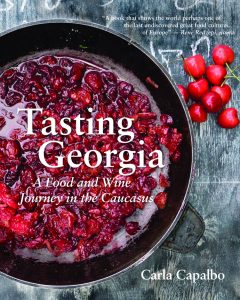

How best to approach this impressive legacy? Carla Capalbo’s Tasting Georgia, written and researched over the last three years, provides an unparalleled level of guidance and immersion. It’s impossible not to feel inspired and curious, leafing through this beautifully presented 464 page monster. Tasting Georgia, subtitled A Food and Wine Journey in the Caucasus, is part travelogue, part recipe book and part guide. If that seems ambitious, it is, but Capalbo pulls it off admirably. This isn’t a surprise – an impressive catalogue of 14 previous books stands her in good stead, however this feels like the magnum opus so far.

Capalbo is an accomplished photographer, and the visual elements of this book are stunning. Her photos evoke not just authenticity, but also intimacy with their subjects. There’s a feeling of being a fly on the wall, and an impressive eye for detail. Recipes are similarly well presented, with inviting food photography and clear descriptions. So far, I attempted only the walnut paste (a key component of the cuisine), which produced a wonderfully flavoursome and authentic result.

Another reviewer felt that the book lacked detail on winemaking or winemakers. I disagree. The seven-page introduction to Georgian wine and winemaking is concise but absolutely complete. There are few summaries of qvevri winemaking which really get down to the fine detail, but it’s all here, including key information about how and why qvevris are lined with wax – a process which is much misunderstood. Capalbo talked extensively with historian and oenologist Giorgi Barisashvili to research this section, and arguably the only better source on Georgia’s winemaking (without seeking out academic papers) is Barisashvili’s own slim volume Making Wine in Kvevri which is difficult to get hold of outside Georgia.

The book profiles 37 traditional winemakers, from the well known (Alaverdi Monastery, Pheasant’s Tears/John Wurdeman, Iago Bitarishvili) to new names that I’m now itching to visit and taste (Dasabami, Mariam Iosebidze, Nika Partsvania). Rather than adopting a static, textbook like format with winery statistics, lists of wines produced or (god help us) star ratings, Capalbo has opted for long format descriptions and interviews with the winemakers and their families. And often, the recipes which follow are culled from the those same families.

It may not be clear to those who haven’t visited the country why Capalbo has opted to combine wine, food, culture, and travel into one book. Her point, I contend, is that it is neither possible nor desirable to split these elements of Georgia’s lifeblood apart. Georgians don’t drink or eat in isolation. They celebrate, discourse and entertain in the context of a supra. Wine and food are the vital fuel that makes this happen.

It may not be clear to those who haven’t visited the country why Capalbo has opted to combine wine, food, culture, and travel into one book. Her point, I contend, is that it is neither possible nor desirable to split these elements of Georgia’s lifeblood apart. Georgians don’t drink or eat in isolation. They celebrate, discourse and entertain in the context of a supra. Wine and food are the vital fuel that makes this happen.

If I have any gripe with this book, it would be the narrow focus on small artisan winemakers who make wine traditionally in qvevris. Whilst this is undoubtedly the most fascinating and unique aspect of Georgian wine, it’s not necessarily the most accessible, and it’s a miniscule part of Georgia’s total wine production. Larger wineries such as Tbilvino, Khareba or Marani now make very good qvevri-fermented wines with good international availability, and perhaps deserved a mention. They’re also increasingly geared up to receiving tourists in quantities that would be impossible for the smaller wineries.

That said, it’s clear that Georgia is winning hearts and minds due to the romance of its culture and the authenticity of its tradition – not necessarily due to its larger more industrial producers. In that and all other respects, Capalbo’s book is a triumph.

Tasting Georgia is published in the US by Interlink books and will be released on September 18th 2017.