Why are wines inherently more valuable when they don’t go with any food but steak?

I got to thinking about this in Tuscany recently, where a helpful chart explains why “great” wines aren’t actually as useful as ordinary wines.

Here’s the setup. Chianti Classicos are some of my favorite wines in the world. They’re delicious, complex, interesting and versatile. But there’s only so much that people will pay for a Chianti Classico: they’re not perceived as “great.”

Naturally, wineries want to make more money. This is why many wineries in the region make an IGT wine outside the classification system, like Antinori does with Tignanello. But those wines and their fabulous ratings, reputation and prices don’t do anything for Chianti Classico. So the Consorzio got the bright idea to create a new top-level, above “Riserva,” called “Gran Selezione.”

Some expensive wines that were already being made as IGTs, like Barone Ricasoli’s Colledilà and Castello di Brolio, now put “Chianti Classico” on the label. The world of status drinkers might get new respect for Chianti Classico.

And that’s a desirable market. Many of us who read Palate Press are like beach bums on Rodeo Drive, mocking the folks who slap their Amex Black cards on the counter to overpay by hundreds of dollars for some fashion that we deem not worth it. We may be cool – I think I am– but if you’re the shop owner, whose business would you court?

All over Europe, the battle between Old and New World style wines rages every day, with a lot of Amex Black card money going for the New World style. Wine regions are caught in the middle. Chianti Classico is smart to chase the American palate as we buy 31% of all wines produced there, far more than any other country including Italy itself.

If “Gran Selezione” on the label meant, “ripe, New World-style wine,” I’d get it. The implication exists in the rules. The required alcohol percentage is only 13%, but that’s higher than for the basic Chianti Classico (“Annata,” 12%) or Riserva, 12.5%. There’s even a requirement for minimum non-reductive extract, which I know is something I look for in a wine.

If “Gran Selezione” on the label meant, “ripe, New World-style wine,” I’d get it. The implication exists in the rules. The required alcohol percentage is only 13%, but that’s higher than for the basic Chianti Classico (“Annata,” 12%) or Riserva, 12.5%. There’s even a requirement for minimum non-reductive extract, which I know is something I look for in a wine.

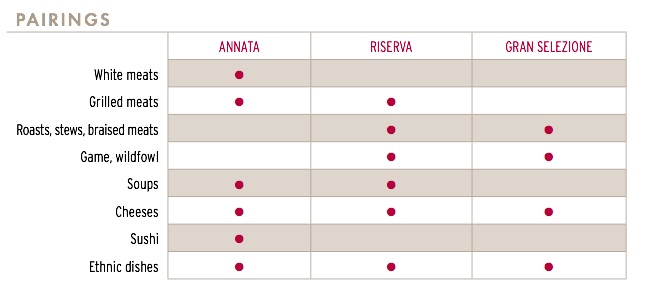

New World-style wines fit the food-pairing chart, which I first saw in a press kit, that shows that Gran Selezione wines, unlike cheaper Chianti Classicos, do not go with white meats, grilled meats, soups or sushi. (They do, however, go with “ethnic dishes,” whatever that means. Tea leaf salad? Navajo fry bread?)

They must be great because you can basically only drink them with steak.

I tasted 47 of these Gran Selezione wines, and while the overall effect was painful the tannins built up much worse than with Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon – there were some beautiful wines.

But when I tasted Gran Seleziones against Riservas made by the same wineries, in four of six cases I preferred the Riserva. That’s not a slam dunk, and it’s because Gran Selezione means different things to different wineries. For some wineries, it means “a wine from our best vineyard.” But more wineries seem to think it means, “the ripest fruit we have aged in new oak barrels.”

The latter wines might get the high ratings the producers seek. Unfortunately it’s the ones I liked – the elegant, balanced Gran Seleziones – that will confuse consumers.

Here are three examples:

Castello La Lecchia Bruciagna Chianti Classico Gran Selezione 2011

Castello La Lecchia Bruciagna Chianti Classico Gran Selezione 2011

I found “the Appollonian ideal of Chianti Classico: cherry and dried cherry fruit, tarriness, chewy tannins. Delightful.”

About Ormanni Etichetta Storica Chianti Classico Gran Selezione 2010, I noted, “Elegant, pretty wine with dried cherry/tar nose and elegant dried cherry on the palate. Tannins have the right mix of silky and chewy. A pleasure to drink.”

But I always had a thought in my head, which I expressed about Castello di Fonterutoli Chianti Classico Gran Selezione 2011: “Good balance, elegant, restrained. Lovely, and just what I want in a Chianti Clsssico. I really want to drink this wine, so that’s great, but at the same time, I don’t know that I’d brag to my car-dealer buddies about it.”

There has been controversy in Tuscany about Gran Seleziones. At a big trade tasting, I went up to Barone Ricasoli’s table to ask company president Francesco Ricasoli about it. He said, “In the last 20 years, the overall quality (in Chianti Classico) has increased a lot. We have room for another step.”

But the man at the next table, Borgo Casa al Vento owner Francesco Gioffreda, interrupted. “What we were doing before as Riserva was understated as a product,” he said. “The Gran Selezione is a mistake. This is why we are not producing any Gran Selezione. We were already doing the maximum (for quality). For a small producer there is no need to do a Gran Selezione.” They glared at each other.

Sergio Zingarelli is currently president of the Consorzio, and he’s also president of Rocca delle Macie, which produces two Gran Seleziones that are not as ripe as most others; one is pungent and green. He’s a big believer in the classification.

“The law changed in 2014,” Zingarelli said. “Last year we presented 29 Gran Seleziones. Now there are 65 wineries that presented to the Consorzio a Gran Selezione. This will increase in the future.”

The Consorzio has an approval process, and Zingarelli said about 20% of the proposed Gran Selezione wines were rejected, but it couldn’t have been too rigorous because some crap wines came in with the good ones.

I wonder if this law could be rethought. It’s Italy; anything could change. But as long as America is their main market, and we persist in thinking that the only great wines are those that aren’t very food-friendly, it’s hard to see why they would. Not unless or until Americans start thinking that steak wines aren’t inherently the greatest wines made.