You’ve likely heard that pinot noir and pinot gris (and pinot blanc) are genetically the same grapes. If you found that unsatisfying, you had the same reaction I did. Obviously they’re not the same. Unless the interns go out and paint all of the pinot noir clusters purple at veraison, different genes are the only way noir and gris will come out noir (black) and gris (grey, but really more of a pinky-bronze). So, frankly, what gives?

What gives are random but well-placed mutations and the genetic flexibility of grapevines in general and pinot in particular. Remember being a kid and thinking that if you got a mutation maybe you’d turn orange or grow a third hand, and your kids would be orange or have third hands too? Mutations actually work that way for grapes. One cell in the right location can pass on any random DNA changes it suffers to its offspring, especially when offspring happen by cutting and grafting instead of vine sex and germinating seeds. In other words, grapevines can pass on somatic mutations – mutations in body cells – and not just germ cell mutations affecting eggs and sperm.

Tiny DNA changes happen pretty regularly in cells for all sorts of reasons. Most are repaired by the molecular clean-up crew dedicated to that job. Most that aren’t repaired do nothing. A very, very few cause changes in proteins that then change the way the cell functions. Most of those changes are totally nonfunctional – cell dies, end of story – or dysfunctional – cell grows into a sickly branch that no right-minded vigneron would dream of propagating into a new vine. Rarely, the change makes a vine bigger, stronger, faster, a different color, a stand-out amongst its peers.

Genetic analyses say that pinot gris and pinot blanc probably happened as separate, independent mutations of pinot noir: in pinot gris, one of two cell layers responsible for berry color is missing anthocyanins; in pinot blanc, they both are. Skin color is the product of a group of molecules called anthocyanins. Mutate an anthocyanin gene, (possibly, with the above caveats) change grape color. The precise type(s) of mutation involved means that cells can flip-flop fairly easily, which is why multi-colored bunches of pinot grapes are common sightings. Non color-related mutations have produced a slew of other pinots with, for example, different fruiting patterns (pinot fin and pinot moyen), hairy leaves (pinot meunier), different growth patterns (pinot droit), and waxless berries (pinot moure).

that pinot gris and pinot blanc probably happened as separate, independent mutations of pinot noir: in pinot gris, one of two cell layers responsible for berry color is missing anthocyanins; in pinot blanc, they both are. Skin color is the product of a group of molecules called anthocyanins. Mutate an anthocyanin gene, (possibly, with the above caveats) change grape color. The precise type(s) of mutation involved means that cells can flip-flop fairly easily, which is why multi-colored bunches of pinot grapes are common sightings. Non color-related mutations have produced a slew of other pinots with, for example, different fruiting patterns (pinot fin and pinot moyen), hairy leaves (pinot meunier), different growth patterns (pinot droit), and waxless berries (pinot moure).

Here’s why we can say that all of the pinot family grapes are genetically the same: the color variations are no more different from each other than different clones of the same color. A wine grape “clone” happens whenever someone propagates a whole bunch of vines from one particular cutting, often on account of desirable characteristics from its own peculiar pattern of random mutations. So, any two famous pinot noir clones – say, pinot noir Dijon clone 777 and Pommard clone 05 – are technically no more or less different than clone 777 is from pinot gris clone 53. We could even say that pinot gris is a different clone of pinot noir that happens to be differently colored. Humans just tend to get caught up on skin color a lot.

In that light, you have to wonder why we make pinot noir and pinot gris into such different wines. In theory, making pinot gris like a red wine should make something that tastes very much like pinot noir, even if it’s the wrong color, and vice-versa for making pinot noir like a white. Champagne and a fair number of other traditionally-minded sparkling wines do the latter. Pinot d’Alsace (a white wine) often includes a mix of pinot colors thrown in, as do some German and Italian whites, and some Californian and Oregonian pinot producers (Anne Amie, Willakenzie, and Domaine Serene are all good examples) make a white pinot noir. Pinot is one of the parents (along with gouais) of chardonnay, and these wines can end up functioning a bit like chardonnay, favorable response to (some) oak included.

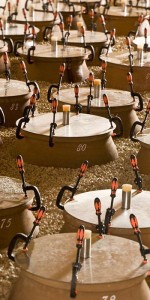

Pinot gris made like a red wine is less common and maybe little more striking, if only for the surprise of being faced with a glass of something decidedly pink and handed a name you usually associate with a white. Most pinot rosés are the product of pinot noir and just a little bit of skin contact, but some producers are making rosés and even salmon-hued orange wines by leaving pinot gris on its skins for days. In Central Otago, Lucie Lawrence at Aurum makes seven different wines from pinot gris, still and sparkling, dry and sweet, white and off-white, including a salmon-hued pithoi-fermented “amber” wine. (Pithoi are ancient Greek clay jars similar to amphorae [or the Georgian qvevri] but designed to stand up by being partially buried in the ground instead of stacked together like the amphorae, and Lawrence had hers made by a potter friend after getting to know a similarly-made Italian wine.)

The complication, whether making over red to white or white to red (really pink to pink), is that we never get a tidy comparison because the wines are never made in exactly the same way as their other-colored sisters. Know of any pithoi-fermented, extended maceration, muslin-strained pinot noir? We can thank the tangled web of wine chemistry for a second complication. Those skin color molecules, anthocyanins, are flavorless. But, anthocyanins react with molecules that affect flavor, so having them around will likely contribute to some minor sensory changes beyond just color.

These wines nevertheless do triple duty as parlor trick, educational tool, and engaging beverage. When I asked my wine-novice husband whom I had told nothing about the Aurum Amber to guess its variety, he named pinot noir on account of the wine’s brambly tannins, “like a blackberry patch without the blackberry.” We both found the wine complex with a distinct beginning, middle, and end: perfumy nose and initial palate impression, driving mid-palate acidity, mouth-filling finish balancing the almond/toasted hazelnut/bruised apple of oxidation and soft-edged, “brambly” tannins. If you’re willing to set aside color-based prejudices and think past the (well-integrated) oxidative notes, the pinot family resemblance is obvious.

So why is pinot the only grape to have suffered such a skin change? It’s not. Chardonnay comes in pink, too, and chardonnay rosé is a rare sighting around (of all places) Chardonnay, France. Muscat d’Alexandria, when red, becomes Flame Muscat. Cleggett Wines in the Australian Adelaide Hills makes a “white” and a “bronze” cabernet sauvignon from color mutations found and deliberately propagated on their vineyard. This sort of thing probably happens fairly often without anyone noticing, or taking the step of propagating it, or thinking to phone the local grape geneticist.

Red wine? White? Pink? We’ve already found that tasters can’t accurately call a wine’s color from smell and taste alone. We’re slowly dropping the red-wine-with-meat, white-wine-with-fish nonsense. Maybe we can get past the idea that grape color determines what you do with it in the winery. Even in this conservative industry, it’s time to stop judging based on skin color.