In his February column, Blake Gray explained why the gradual extinction of some wine styles is not always a tragedy.

Today I take pleasure in upending one of the most common wine story tropes: the “disappearing underappreciated wine” story.

These stories play the emotions like a zither: loss, urgency to act, the opportunity to be one of a special group of people who appreciate exotic beauty. I’ve written a bunch of them: about Madeira, artisan sake, restrained California Zinfandel, etc.

But do you ever read the other side — this wine is disappearing, and that’s a good thing?

But do you ever read the other side — this wine is disappearing, and that’s a good thing?

Welcome to Rivesaltes.

Sweet, but no dessert

Before you say, “I couldn’t care less about Rivesaltes” and click away to see 5 Weird Tricks Make Your Hair Sexier, let me add that there’s a larger story as well about sweetness in wine, and at what point in the day we want it.

Here are a few numbers that don’t seem to add up. A lot of frequent wine drinkers in the US say they “strongly prefer sweet wine,” according to the Wine Market Council, including 40% of millenials, and 20% of baby boomers.

Yet dessert wine sales dropped 8% in 2012 and are about where they were five years ago, according to the Wine Institute. Table wine sales have grown 15% over the same period.

Americans aren’t drinking as much dessert wine. What they are doing is drinking sweeter wines with dinner — hence the phenomenal growth for Muscat and blends like Apothic Red. Maybe you don’t need dessert wine after that.

But Rivesaltes could get by without American sales; it was never a big deal here anyway. In France, though, it was a huge success, selling 70 million bottles every year in the mid-1900s, according to Jancis Robinson. Now, fewer than 3 million bottles are sold each year.

Going dry

French society has changed, and here comes the zither. People don’t drink wine with lunch anymore. Young French people drink more beer and spirits. Tough drunk-driving laws have devastated rural restaurants and eliminated that glass of dessert wine at the end. All true. Man, I just love that zither, makes me want to weep.

French society has changed, and here comes the zither. People don’t drink wine with lunch anymore. Young French people drink more beer and spirits. Tough drunk-driving laws have devastated rural restaurants and eliminated that glass of dessert wine at the end. All true. Man, I just love that zither, makes me want to weep.

Thing is, and let me put this delicately so I don’t offend anyone: Rivesaltes sucked.

No, let me rephrase that. Here’s Jancis from the Oxford Companion to Wine: “If the overall quality (of Rivesaltes) is more varied that that of Banyuls or Maury, it is improving, largely thanks to the efforts of Domaine Cazes.”

She’s so polite. I went with a group of journalists to Domaine Cazes, and Emmanuel Cazes was so uninterested in Rivesaltes that he didn’t pour us any. He’s using grapes that used to go into Rivesaltes to make dry wines, and that’s going so well he’s expanding.

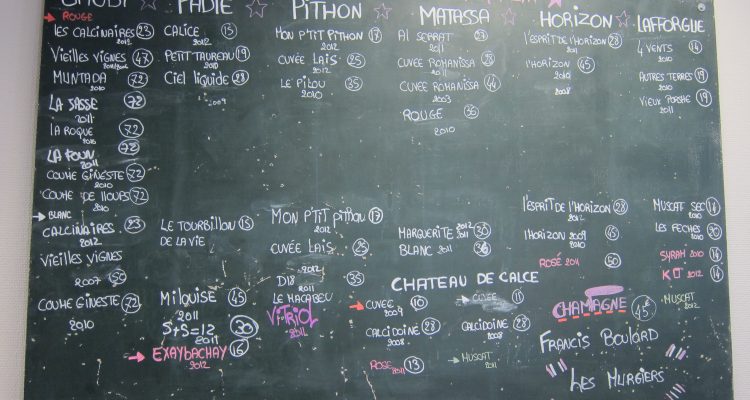

Another Rivesaltes area winemaker, Olivier Pithon, says, “The problem with Rivesaltes is it’s not very good. I want to make wine with personality.”

His Domaine Olivier Pithon La D18, a biodynamic wine made from old Grenache Gris and Grenache Blanc vines that used to go into Rivesaltes, is outstanding: intense, fresh and stony, with a citrus pith character. We tried a taut 2011 and a delicious 2007 that shows how well it ages. Should we mourn the vineyard pulled from Rivesaltes production for this wine?

His Domaine Olivier Pithon La D18, a biodynamic wine made from old Grenache Gris and Grenache Blanc vines that used to go into Rivesaltes, is outstanding: intense, fresh and stony, with a citrus pith character. We tried a taut 2011 and a delicious 2007 that shows how well it ages. Should we mourn the vineyard pulled from Rivesaltes production for this wine?

Let’s not just pick on Rivesaltes here. Jancis calls Banyuls its superior, writing, “Banyuls and Banyuls Grand Cru are the appellations for France’s finest and certainly most complex vins doux naturels” in the Oxford Companion.

Guess what? People aren’t drinking Banyuls either.

“I travel all over the world and I pour people the Banyuls,” says Jean-François Deu of Domaine du Traginer. “They like the wine, but they don’t buy it.”

Endings and new beginnings

Robinson visited Collioure, the main town for producing Banyuls, last year and reported that there’s only one working cellar left. Picturesque, seaside Collioure, with its old vineyards of Mourvèdre and Grenache and nobody local left to tend them. Cue the zither … but wait, there’s tuba and alto sax!

Turns out that the depressed prices for vineyards in Collioure has made them available for some of the young, ambitious winemakers in the nearby Rivesaltes region, except they don’t call it Rivesaltes for dry wines, they call it Roussillon. Because Rivesaltes is disappearing, and we’re not sorry.

Anyway. In Collioure, instead of deliberately overripe, shriveled grapes going into barrels to meet up with grain alcohol, now we’re seeing more of what the grapes can do when they’re picked for dry wine. Cazes is expanding there, and taking the vineyards he buys biodynamic. Deu is making much more dry wine.

It’s ironic, this market shakeout for dessert wines, but it might get even more extreme in the future. While the Wine Institute reports 7.6% of all US wine sales are dessert wines, Wine.com says just 1.3% of its orders in 2013 were for dessert wines. The dessert wine market has farther to fall.

There’s going to be a winnowing, and Rivesaltes and Banyuls might not make the cut. But it’s worth noting that wine technology has changed since the time when vintners in those regions decided sweet wines were the highest and best uses of their grapes. Viticulture is more precise. Refrigeration is widely available. Dry wines can be made there now that weren’t possible even 30 years ago.

There’s going to be a winnowing, and Rivesaltes and Banyuls might not make the cut. But it’s worth noting that wine technology has changed since the time when vintners in those regions decided sweet wines were the highest and best uses of their grapes. Viticulture is more precise. Refrigeration is widely available. Dry wines can be made there now that weren’t possible even 30 years ago.

You want a parallel? It’s like the rise of Côtes de Gascogne wines in the region where all the grapes used to go into Armagnac. Armagnac is still great, but it’s possible to make delicious dry table wines there now in a way that wasn’t before.

My favorite wines from my visit to Côtes du Roussillon were from Domaine Gardiés. Jean Gardiés is in love with Mourvèdre-based blends, and his La Torre Côtes du Roussillon Villages 2011 is terrific: potent, ripe red fruit with plenty of minerality, a meaty texture and a long finish. It’s elegant and yet fruity, the kind of delicious organic wine we could use more of in the US, and I just couldn’t get enough of it. I hope he gets ahold of one of these suddenly affordable old vineyards in Collioure, because I’d like to taste what he can do with it. Cue tuba and alto sax.