If you’re at all interested in French wine, you’ve heard that parts of Bordeaux were smashed by multiple severe hail storms this past July, August, and September. While many of the swankiest appellations were spared, damage to parts of Entre-Deux-Mers, along with Sainte-Estèphe and Pauillac, was flabbergasting. Some vineyards lost everything – photos show vines ripped bare of all leaves and fruit – and sustained trunk damage that will affect next year’s crop. Current estimates say that at least 4-8% of the total Bordeaux crop was lost.

A dark and stormy plight

Hail happens when a thunderstorm with particularly strong updrafts meets supercooled water droplets (liquid water droplets surrounded by colder-than-freezing air). When the water droplets run into a tiny bit of something cold, like a bit of ice or some frozen dust – a nucleus – they freeze on. When the frozen bit encounters more water droplets, they, too, glom on. The resulting ice pellet is bounced up and down in the storm cloud, collecting more water droplets along the way, until the ice pellet becomes heavy enough that the rising warm air currents are no longer powerful enough to keep it aloft. It falls out of the cloud, and we have hail.

Bordeaux almost never gets snow – temperatures barely drop below freezing in the winter – but hail hits with disturbingly irregular frequency. The Entre-Deux-Mers appellation has been smashed in 2011, 2009, 2008, 2003, and 1999. Hail intensity over France increased by 70% between 1989 and 2009; and though the frequency of hailstorms didn’t increase, the amount of hail they dropped did. That might mean more in the context of global warming if we understood why hail falls on this part of France so often, but even the best conclusions on that topic aren’t unambiguous.

The Association Nationale d’Etude et de Lutte contre les Fléaux Atmospheriques (ANELFA) – which, fantastically, translates to something like the “National Association of Study and Struggle Against Atmospheric Scourges” (why can’t we be this dramatic in English?) – says that hail does about half a billion Euros worth of damage to French crops each year. Even with the wine industry’s market value at over €25 billion, that’s not an insignificant number, and it’s certainly not insignificant to the handful of vineyards – most news-worthily in Bordeaux – that have suffered repeated hits in recent years.

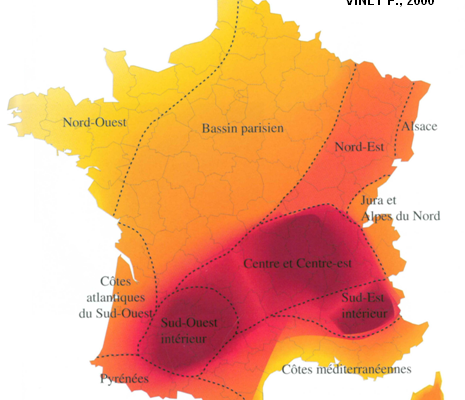

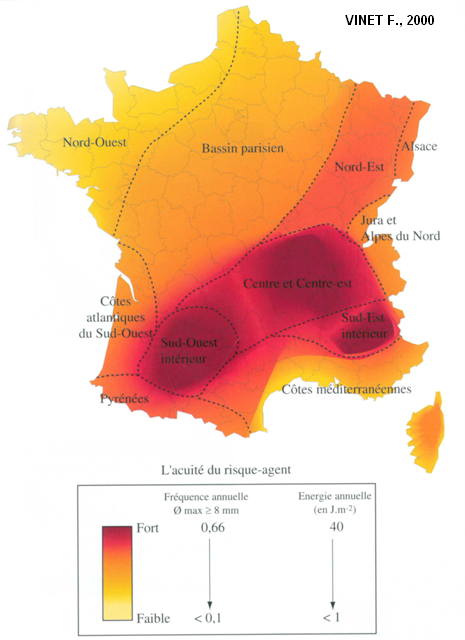

According to ANELFA, Bordeaux lies just north of the part of the country with the highest risque de grêle [risk of hail].

Man has been battling hail since the late 1800s, with a variety of on-again, off-again national and international hail prevention experiments trying to do something about wild and unpredictable damage to crops and property. The ANELFA exists, in fact, expressly for the purpose of exploring “artificial weather modification aimed at suppressing hail.” This is a big deal.

Seeds of doubt

Silver iodide cloud seeding is the most popular strategy for playing God with the clouds. The basic idea behind cloud seeding is that, by increasing the number of particles in a cloud that can serve as nuclei around which moisture can gather, we can promote rain drop formation and increase precipitation. Moisture can remain suspended in the air – that’s what a cloud is, after all – and won’t fall as precipitation unless it’s given some excuse to collect into bigger, heavier drops. Cloud seeding provides particles – nuclei – to serve as that excuse. This strategy is used to increase rainfall over areas that need it, but it also alleviates hail by lowering intra-cloud temperatures, inducing rainfall before hail can form, and making smaller hail.

Silver iodide is thought particularly effective for this purpose because it structurally mimics ice crystals and it’s easy to generate by burning an acetone silver iodide solution in small ground-based generators. Ground generators, ideally spaced about 10 km apart, can be started up by landowners themselves about three hours before an anticipated hail event and run until they receive a message that the hail risk is over. Rockets or airplane dispensation are other options. Right now, the ANELFA has about 650 generators distributed over four regions, including Bordeaux and parts of Provence. They estimate some degree of success based on a 40% drop in hail-related insurance claims in the covered areas.

Hail seeding is an annual event in places like Alberta and North Dakota, where the goal is keeping hail small enough that it doesn’t wreck cars. That seems to work. Still, we can’t conclusively say how well hail seeding works to protect Bordelais vineyards. After all, it’s impossible to say how much hail would have fallen sans intervention and, since hail patterns vary so dramatically and rapidly, we can’t just compare treated and untreated regions. Some experiments have gone woefully awry – a hail seeding program in Colorado in the 1970s saw as much as a 500% increase in hail fall – but that hasn’t stopped us from trying. The idea of being able to control something so frighteningly unpredictable as the weather is just too appealing.

Dripping silver iodide all over the countryside sounds dangerous, but it’s probably not. Even though silver iodide is toxic to humans and animals in high doses, multiple studies repeated in a variety of locations around the world have evinced that the amounts used in cloud seeding have essentially no environmental impact. Some environmental groups are still worried, especially regarding seeding over wildlife refuges harboring adorable mammals (the Australian pygmy possum, for example). The Bordelais seem less concerned about the silver iodide and more concerned about protecting their wine industry.

Hail is hearty

There are, naturally, alternatives. Europeans have tried to scare hail away with loud noises for centuries; the then-common practice of ringing church bells to mitigate hail fall was outlawed by the Parisian parliament in 1786 because so many bell ringers were struck by lightning in the line of duty. In a more contemporary manifestation, we have the hail cannon: a giant upwardly-facing cone that directs the force of an explosion toward the offending cloud. They’ve been around since the mid-1800s, fell out of favor when research suggested they didn’t work, and are now being sold again because… well, we all have control issues, right?

Hail netting – which is exactly what you think it is: netting to shelter plants from hail – is relatively common in apple orchards, very common in vineyards in Argentina’s Mendoza region, and provides reliable if moderate protection. It’s still not likely to show up much in Bordeaux, though, because in addition to holding back hail, these nets shade the vines enough to slow ripening; a good thing in Mendoza, but not a good thing in Bordeaux.

So, are the Bordelais stuck? Controlling the weather works about as well as trying to control any other large force of nature: middling to fair at best. Physically guarding vines from hail has impractical extra consequences. Picking the vineyards up and moving them to a less hail-prone area isn’t likely to happen any time soon. In the end, we (and they) may just have to acquiesce to the conclusion at which farmers, it seems, inevitably arrive. In the battle between man and nature, nature often wins.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/yoga-headshot-2010-thumb.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Erika Szymanski was blessed with parents who taught her that wine was part of a good meal, who believed that well-behaved children belonged in tasting rooms with their parents, and who had way too many books. Averting a mid-life crisis in advance, she recently returned to her native Pacific Northwest to study for a PhD in microbial enology at Washington State University. Her goal, apart from someday having goats, is melding a winery job to research on how to improve the success rate of spontaneous ferments. When tending her Brettanomyces leaves enough time, her blog Wine-o-scope keeps notes on why being a wine geek is fun.[/author_info] [/author]