Amidst the discussion among wine writers on just how much “natural wines” should be included in wine lists, I am flipping through a 50-page wine list in one of Siena, Italy’s more renowned osterias.

“So, anything interesting in there?” my Significant Other wonders, me being lost among wines of Italy’s wine regions.

“No”, I reply. “What do you mean? There must be something in there. We’re in the heart of Tuscany!”

But there isn’t, at least not for me. The huge list is almost entirely built around the “big guns”, the Supertuscans. Little natural wine is in sight here.

I caught the natural wine bug in the early 2000s and have built my tastes around it ever since. To blame are a handful of wine producers in the Northeastern Italian region of Friuli-Venezia-Giulia—namely Princic, Vodopivec, Radikon and Gravner. The natural movement itself has come a long way since then, spurring heated debate among connoisseurs, both on- and offline, along the way. Hence my disappointment at finding so few serious options for the night in the Sienese institution. Sure, some nice Burgundy producers were listed, but I wasn’t going to drink Chardonnay here.

The next day I raise the issue with Helena and Dante Lomazzi of Colombaia natural winery as I visit their domaine in Val d’Elsa, 30 minutes north of Siena. “You will find very little, if any, of our wines on Italian wine lists. We sell almost all of our 10,000-bottle production outside Italy, mainly in the UK, Canada and the US”, says Dante Lomazzi.

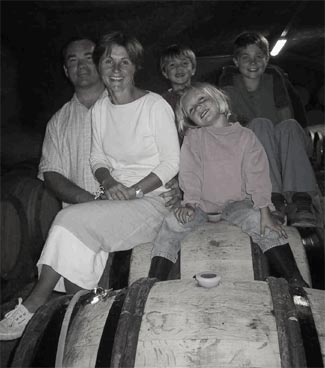

Having left successful media and communication careers in Milan in 2003, the couple now runs a small, four-hectare biodynamic estate, growing authentic regional varieties—malvasia, trebbiano, sangiovese, colorino, malvasia nera and canaiolo. Helena and Dante believe that the “big” wine industry (i.e., mass-producing wineries that do not abide by organic philosophy) is still running very strong, especially in Italy.

Helena stresses the importance of going natural, for ecological and health reasons. “Big companies do not understand that using chemicals in the vineyards is polluting the land. And that’s a problem,” she says as they take me through a cellar the size of a one-bedroom apartment.

On the way, I learn that just the two of them are involved all year round in production—doing everything by hand, even labeling. Their carton packaging carries a promise: “100% grapes”, a clear sign of dedication to chemical-free agriculture. “People are starting to taste more and more, understanding the benefits of natural winemaking. And, once you taste, it’s hard to come back to something with added chemicals. This is the new consciousness,” Helena says.

So, even without being included in wine lists, the natural wine movement seems to be winning over more fans.

Natural Wine on Display

I first met the Lomazzis at this year’s RAW and Real natural wine fairs in London. Specialized in showcasing the work of natural winemakers from around the world, events like these are gatherings of small, family-run organic estates. Both events were packed — proof enough that the natural wine movement is growing. Elsewhere in Europe, Italy has had a good run with the Vini Veri natural wine fair in Cerea and VinNatur just outside Verona. Millesime Bio in Montpellier, France, is the place to be if you’re a natural wine lover. In a sort of “recognition” of the importance of natural wines, a mainstream industry event, VinItaly, dedicated a separate exhibition space for the bunch in 2012, called ViViT.

Although debate continues about how exactly to define natural winemaking, most naturalists would agree that the estate should have an organic certificate, attesting that no synthetic chemicals or pesticides are allowed in the vineyards and only native yeasts are used. Some winemakers do not filter wines or control fermentation. A significant amount, if not all, of natural production is based on authentic grape varieties. The accent is on quality over quantity, which is why many winemakers consider annual production bigger than 100,000 bottles not worthy of a natural label.

“We need to work with nature, not fight it.”

New wine-consciousness is very much on the mind of Arianna Occhipinti. Being a producer since 2004, she is still relatively new in the winemaking world. Although she has had a relatively short career, this dark-haired native of Sicily holds almost cult status among the natural wine geeks in the US. “Natural wines are not fashion. If you have real passion in wines, you go the natural way,” Arianna proclaims (passionately) as we chat at ViViT.

On 15 hectares outside Vittoria, she works with native varieties nero d’avola, frappato, albanello and moscato. Arianna relates winemaking to Sicilian tradition and talks of local producers coming back to authentic grapes. “There was a crazy period of international grapes on Sicily in the last 20 years. People abandoned the gold of our place and planted international varieties that were more productive. But now people are replanting with local grapes and finding new potential”.

Arianna’s philosophy is to put the grape into the bottle without adding anything in between. Respect for the soil creates the future of winemaking. “Only this way we can show the real expression of our terroir.”

Her words are very much echoed by a French natural winemaker Eric Texier, who lives and works in Charnay in the Rhône valley, the place he calls the birthplace of Syrah and Roussane grapes. “We need to work with nature, not fight it,” Eric told me during an interview at the RAW wine fair.

He talks passionately about Brézème, a unique terroir that he describes as “Southern Rhône soil in Northern Rhône climate”. “We have the body of limestone from the south, but freshness of the northern climate.” Eric is clear about natural winemaking formula: 95% of winemaking success consists of what is in the grape; and 100% of the grape comes from the soil. Just 5% is winemaking, he says.

“It is better to use mechanical weeding than chemical. It is better to use sulfur rather than systemic compounds. All in all, the benefits of natural winemaking are bigger than the risks.”

The next step in natural winemaking, he says, is to abandon plowing, quit using fossil fuel and try to create an interaction between the vines and what grows naturally on the soil.

Growing Local Varieties

The natural wine movement is now gaining ground across Europe. Do a Google search and you will find organic wineries in Spain, Austria or Germany. Or Slovenia, where Primož Lavrenčič of Burja Estate organically grows local varieties such as laski rizling, zelen and malvasia. “Chardonnay should be planted in Burgundy and the New World. But here, I want to plant the grapes that are part of our identity, our history,” Lavrenčič says. “I’m trying to step back, trying to understand how to encourage nature, most of all the soil, to express itself in the best way in my wines. Or even better, I’m trying to diminish my influence overall.”

One of the varieties he wants to plant in his native Vipava Valley, blaufränkisch, has not been recognized under Slovenian law as of controlled origin. “We were forbidden to plant blaufränkisch here after the Second World War. But my father remembers it from before, this was its natural habitat,” Lavrenčič says.

He is adamant to walk to road of his predecessors and committed to reviving the grapes historic to Vipava rather than the international ones.

“If others grow merlot here, I will grow blaufränkisch.”

Growing it means that Lavrenčič might sacrifice the controlled origin seal. But this is not the first time that I’ve met a rebel winemaker among the natural wine bunch. “Either the system is wrong to not support planting of authentic varieties here or I am wrong. We shall see!” Primož says.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Marko.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Marko is a partner at Label Grand, a fine wine consultancy based in Central and Eastern Europe. [/author_info] [/author]