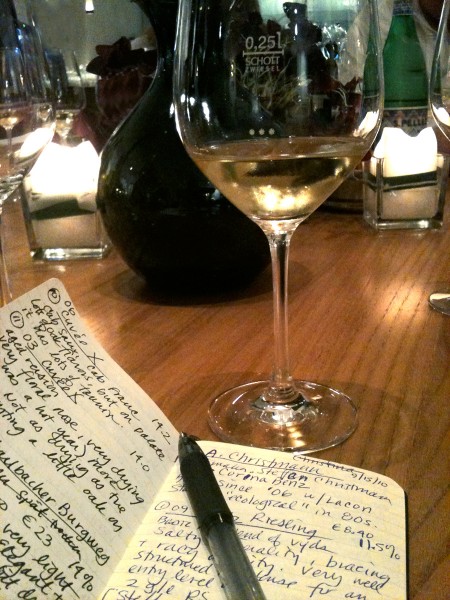

Pour a glass for each of us. Now, what does this wine taste like? You get apricot, I get peach. You like the acidity, I think it’s too much. You get a whiff of spearmint, I think it smells like wet stone and sage. But we agree it’s great with the scallops.

We taste wine with four of our five senses: sight, smell, touch, and taste. (Hearing isn’t involved, but sound can be a distraction. Have you ever tried to taste Burgundy in a noisy bar?) “Tasting” wine, so-called, isn’t only about taste, about the wine’s flavors. It’s also about its color, aromas, temperature, and texture across our palate. Tasting wine requires us to tune into a mix of signals entering our sensorium, then make sense of the mess.

Because taste gets so readily entwined with memory, tasting wine provokes private resonances, too, which add complexity to the task of understanding a wine’s effect. If you drank a Barbaresco on the last night of your honeymoon in Piemonte (lucky you), your affinity for that experience will color your perception of any future Barbaresco. You get Piemonte, I get Terroir Wine Bar.

So there’s no right answer to that question at the top, “What does this wine taste like?” But there is an answer—your answer. Since wine is social, it can be helpful to learn how to talk about what you’re tasting, to develop a vocabulary that lets you share your experience with others. Language is the best (only?) way to share each other’s impressions of a wine, to understand its evocations both physical and metaphysical.

I call our ability to translate taste into words “taste literacy.” We learn visual literacy from a tender age, and as adults can distinguish even subtle gradations in the visual field. If I say “brick red,” “fire engine red,” and “maroon,” you can readily imagine these colors and describe the differences between. But it’s harder with flavors. When I say “apple,” “pear,” and “quince,” do you quickly conjure all these flavors in your mind? What adjectives would you use to describe them? Apple might be reasonably easy, but how would you characterize quince? Now try guava, mango, and papaya.

Still, there are broad tasting categories about which there’s more mutual agreement. These generally include the principal flavors our taste buds readily distinguish: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. But there can also be good consensus about other factors, too, including the wine’s most pronounced aromas and flavors. Citrus is a good example. Your citrus might be lemon, and mine might be lime or tangerine, but we’re both getting that tropical fruit-flavored acidity we readily associate with citrus. When I say “citrus,” you get it.

Still, there are broad tasting categories about which there’s more mutual agreement. These generally include the principal flavors our taste buds readily distinguish: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. But there can also be good consensus about other factors, too, including the wine’s most pronounced aromas and flavors. Citrus is a good example. Your citrus might be lemon, and mine might be lime or tangerine, but we’re both getting that tropical fruit-flavored acidity we readily associate with citrus. When I say “citrus,” you get it.

I recently taught an introductory class on wine sensory evaluation—how to taste wine, and how to talk about it, too. Over the course of about an hour and a half, a class of beginners was able to move from a place of having virtually no words to describe a wine—any wine, really—to being able to use a handful of terms with confidence. We got there by focusing on the broadest categories of wine tasting experience, those primary factors that almost every wine has to some degree, and looking for them in just six example wines: two whites, a rosé, and three reds.

At the start of the class, I handed out a short glossary of tasting terms, plus a good article on wine tasting for class members’ later perusal. I briefly described our olfactory system, the mechanism for processing aromas and flavors. Then I walked us through the simple steps of tasting: first observe a wine’s color, then swirl, sniff, and taste; observe its texture; observe its finish. I told them about the cues to look for at each step, but I was primarily concerned with making this process seem easy, fun, and not even remotely mysterious.

The key to the class’s success lay in simplifying the tasting exercise by focusing on just a few factors—ones about which there’s more mutual agreement—and offering participants a short list of descriptive terms that let them wrap these factors in language.

The average Palate Press reader is probably quite familiar with this way of thinking about wine, and reasonable fluent when describing wine for others. But many readers may know (or live with) others who are curious about wine but flummoxed when it comes to talking about what they’re tasting. This article is for them.

High, Medium, Low

Before any discussion of acidity, tannin, sweetness, fruit, or alcohol, it can be helpful for new tasters to think of a wine simply as hitting a range of high, medium, and low notes. (Although the notes metaphor is auditory, one could also think of this spatially, with some elements sitting on top, some in the middle, and some reverberating underneath.) Any given wine might offer more of one than another, but most wines have a mix:

Before any discussion of acidity, tannin, sweetness, fruit, or alcohol, it can be helpful for new tasters to think of a wine simply as hitting a range of high, medium, and low notes. (Although the notes metaphor is auditory, one could also think of this spatially, with some elements sitting on top, some in the middle, and some reverberating underneath.) Any given wine might offer more of one than another, but most wines have a mix:

- The wine’s acidity, alcohol, sweetness, and bright fruit flavors contribute high notes. High notes are sharp, juicy, and clean.

- Medium notes are contributed by a broad range of factors, including fruit, sugar, and alcohol. Medium notes are broad, spreading, and mouth filling.

- Low notes are contributed by the wine’s tannin, earthiness, and darker fruit flavors. Low notes are dark, savory, and grippy.

This tiered way of thinking makes it easy for both spatial and visual thinkers to grasp the various flavor components of the wine—its rough structure, if you will—and separate them into broad categories. It matters less whether a taster classifies a blackberry flavor as a “low note” or “medium note,” and more that she notices it occupies a qualitatively different space from the heat she’s also feeling (from alcohol), and the drying sensation she gets at the end (from tannin). She’s learning to pay attention, in other words, and to classify different taste sensations as, well, different.

Seven Key Factors, Broadly Speaking

Once tasters have learned to tune into high-medium-low, they can begin to add more specificity to the tasting experience. Below are the seven factors—essential to almost all wines—that I chose to present to the class. Your list might be different, but the attendees seemed to find these easy to work with. The physical and physiological information helps tasters understand what’s happening in their palates, and the suggested tasting terms give them words to describe it.

Acidity

All well-made wines are at least moderately acidic, and white, rosé, and sparkling wines are generally more acidic than reds. For the science geeks: wine’s pH ranges from 2.9 to 3.8, and its acids include tartaric, malic, lactic, acetic, and succinic (citric acid is sometimes present, but only if it’s been added by the winemaker to boost acidity). Acidity presents itself as tanginess or sourness, stimulating the salivary glands beneath your tongue; in this way it’s both a flavor and a sensation. Acidity makes wine refreshing, cleansing, and food-friendly. I think of acidity as contributing high notes to the wine. Some tasting terms:

- “tangy, sour, juicy, citrusy, sharp, tart, crisp, bracing, refreshing, lively, flabby (if the acidity is too low);”

- “citrus, lemon, lime, green apple, vinegar (not a good thing!).”

Sweetness

The perception of sweetness in wine is contributed by sugar itself, by the wine’s alcohol, and by certain aromatics that we associate with sweetness but aren’t truly sweet, like vanilla from toasted oak barrels. We sometimes describe sweetness in wine as happening “at the front of the palate,” but all taste buds on the tongue sense sweetness. A wine can also smell sweet, although this sweetness is often contributed by flowery aromatics found in grapes, especially muscat and riesling. Table wines that have been fermented to dryness actually have very little residual glucose and fructose sugars, generally between 1 and 5 g/L. Even wines with a higher amount of remaining sugar might not taste sweet provided the acidity is high enough to balance it out. I think of sweetness as contributing high to medium notes to the wine. Some tasting terms:

- “Sweet, sugary, floral, honeyed, jammy, saccharine, cloying;”

- “Raisin, dried fruit, flowers, vanilla, caramel.”

Fruit

Finished wine often retains some of the primary flavors of ripe grapes. Fresh syrah fruit tastes a little bit like blackberry and black pepper, and you’re likely to find these flavors in the wine, too. But fermented grapes also take on the flavors of many other fruits: stone fruit, pome fruit (e.g., apples and pears), berries, citrus, and tropical fruits. These secondary fruit flavors from fermentation add to the finished wine’s complexity and interest, and spawn a slew of adjectives in the tasting note. As noted, fruit and sweetness are easily confused, and for the beginning taster, it’s enough simply to try to try identify one or two fruit flavors in any given wine. I think of fruit as contributing a range of notes: high (citrus, melon), medium (stone fruit, tropical fruit), and low (blackberry, black cherry). A few tasting terms:

- “Fruity, jammy, citrusy, plummy, peppery;” usually not “grapey” unless the wine is made from native American or hybrid grape varieties;

- “Cherry, plum, apricot, peach, stone fruit, blackberry, bramble fruit, strawberry, melon, apple, pear, citrus, tropical fruit.”

Body

Body refers to the weight of the wine in your mouth, an effect due primarily to alcohol. It can be helpful to look at the wine’s stated alcohol content and learn to correlate this with the perceived heft of the wine on one’s palate. In broad terms, alcohol levels from 7–11% will feel light-bodied; those from 11–14% will feel medium-bodied, and anything higher will feel heavy or full-bodied. A wine’s alcohol level directly correlates with the fruit’s sugar content at harvest: higher ripeness equals more sugar to ferment equals higher potential alcohol. Higher alcohol wines are often called “hot” or “big.” The amount of color and aromatic compounds drawn from the grapes during fermentation also affects the perceived weight of the wine, and an over-extracted wine can likewise feel “big.” With body, don’t worry about fancy descriptors, just keep it simple:

- “Light, medium, heavy.”

Tannin

Tannic acids derive from the grape skins, seeds, and stems, and from the oak in aging casks. Tannins in wine—generally far higher in red than in white—bind proteins in saliva, literally drying out the inside of the mouth. In this way, tannins are perceived more as a texture than a true taste, although some people are quite sensitive to tannin and describe it as bitterness. Tannin gives wine structure and heft, a backbone to which other elements attach. Aging softens tannins, which precipitate out of the wine to form harmless sediment at the bottom of the bottle. I think of tannin as contributing a low note to the wine. Some tasting terms:

- Young wines: “drying, astringent, grippy, stemmy, oaky, bitter, green, tea-like;”

- Older wines: “dusty, supple, smooth, integrated.”

Bouquet

It’s hard to say this word without sounding sardonic, so roundly has it been lampooned. But technically, bouquet simply refers to the aromatic notes derived from cask and bottle aging. For new tasters, I think the term is most useful to describe the aromas and flavors they don’t associate with fruit, acidity, alcohol, and sweetness. This includes toasty and oaky notes, yeastiness (often found in sparkling wines), and the savory, integrated complexity of older wines. The bouquet contributes medium and low notes, to my mind. A few descriptors:

- “leesy, yeasty, umami, buttery” from fermentation;

- “oak, toast, caramel; oxidized, nutty” from cask aging;

- “savory, integrated, supple” from bottle aging.

Minerality (extra credit)

Minerality (extra credit)

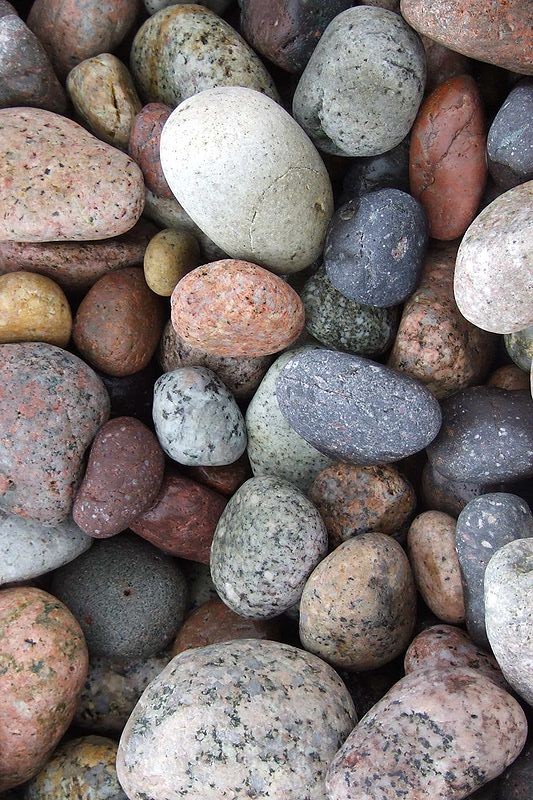

Minerality is a somewhat controversial term, as there’s limited scientific consensus about how aromas and flavors of stone or earth come to be present in wine. But many tasters do report mineral notes unmistakably present in some wines, especially those grown on charismatic soils, including Chablis (Kimmeridgian clay and chalk), German Riesling (slate), Aglianico (volcanic rock), and Albariño (alluvial soils, but salty). I envision minerality sitting somewhere at the bottom of the wine—as a low note, in other words—but perhaps I’m just suggestible. Anyway, extra credit if you can detect these as a beginner (I bet most can):

- “earthy, briny, smoky, stony, steely;”

- “limestone, flint, slate, salt, stone, wet stone, fusel, petrichor.”

In hindsight, this seems like a lot of material to have thrown at a class of beginners. But I guarantee it’s much easier with a glass (or six) at hand, plus focused time to taste, observe, and reflect—and then to talk with others about what you’re tasting.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://palatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/meg2.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Meg Houston Maker is a writer curious about nature, culture, food, wine, and place. Find her essays about the pleasures of the table at Maker’s Table, and follow her on Twitter @megmaker.[/author_info] [/author]